Auxiliary breathing (Latin auxiliare = to help) is characterized by the fact that the auxiliary breathing muscles are switched on in order to adapt breathing movements to requirements and to improve lung function.

What is auxiliary breathing?

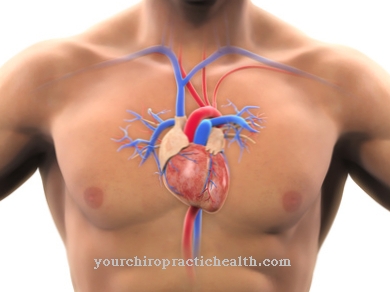

In a healthy person, breathing in at rest is only accomplished by the main muscles, the diaphragm and the outer intercostal muscles, which expand the lungs via the chest.

The exhalation proceeds under the same conditions, but completely passive. The inhalation muscles relax and the stretched lungs pull back to their original position. It is the same principle as with an inflated balloon: When the air escapes, it contracts without any external force.

Only when the body demands increased breathing does the auxiliary respiratory muscles provide support. This situation occurs, for example, when exercising, singing or screaming, but also with respiratory diseases that limit lung function and lead to shortness of breath. Depending on the cause of forced breathing, either the auxiliary muscles of inhalation or exhalation can be used or both groups can be used together.

Function & task

Auxiliary breathing and its intensity depend, among other factors, on the breathing mechanics. This is characterized by the special construction of the system in which the lungs follow the movements of the chest and vice versa.

When you inhale, the chest expands and pulls the lungs with it. This creates conditions so that more air can flow in. Only the two main muscles are necessary for this at rest. The diaphragm expands the lower part of the chest, the other muscles the upper part.

The process is controlled by the breathing center in the brain. When the receptors in the blood report an increased need for oxygen to the respiratory center, pulses are sent from there to force inhalation. Such situations arise during physical exertion, mental tension or a disease of the respiratory system.

Under these conditions, the main muscles are no longer sufficient and additional muscles are used to intensify inhalation. This basically includes any muscles that can expand the thorax, such as the pectoralis major and the muscles that pull from the upper ribs or collarbone to the cervical spine. The basic requirement for these muscles to function in this way is that they have their fixed point on the shoulder girdle or on the cervical spine.

When you exhale, the lungs contract again because the tension in the inhalation muscles eases and the chest moves with it. When you exhale more intensely, this process is no longer passive, but is supported by muscles that compress the chest. These are, for example, the abdominal muscles, the large pectoral muscles and the hip flexors. They reduce the space between the pelvis and the lower ribs, which compresses the rib cage. This pressure is transferred to the lungs and increases the amount of exhalation. In this case, the external components, pelvis and shoulder girdle, unlike inhalation, must be able to move towards the thorax.

Inhalation and exhalation cannot be functionally separated. That is why both components are always included in the auxiliary breathing when the stress is greater. The benefits are obvious: the consequences of temporary or manifest shortness of breath can be eliminated, mitigated or at least made tolerable.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines for shortness of breath and lung problemsIllnesses & ailments

All diseases that are associated with shortness of breath require auxiliary breathing to ensure the body's need for oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide. This includes lung diseases in the narrower sense, but also impairments of the breathing mechanics.

The lung and respiratory diseases are divided into 2 categories. The restrictive ones, for example pneumonia and diseases of the lungs, and the obstructive ones, including chronic obstructive bronchitis and bronchial asthma.

In the case of restrictive ailments, inhalation is initially impaired. That is why the auxiliary muscles for inhalation are used here. This can be seen when people hold their heads upright and stretch their arms up and try to inhale as deeply as possible. The head and arm position stretch the chest and neck muscles and pull the chest up a little.

Obstructive respiratory diseases initially have a negative effect on exhalation, which is why the auxiliary muscles of exhalation are used. A typical application example is the so-called coachman's seat, in which people who are currently suffering from shortness of breath during exhalation support themselves with their elbows on their thighs. This provides relief, since on the one hand the upper body weight no longer has to be carried and on the other hand the abdominal and chest muscles can better support the exhalation.

An impairment of the respiratory mechanics often affects the expansion of the thorax and thus inhalation. The ability of the thorax to expand is determined by the mobility of the thoracic spine and the ribs. There are various diseases that hinder or limit precisely this function. This includes processes that lead to a stiffening of the spine, such as Bechterew's disease or osteoporosis, but also inflammatory processes that prevent the ribs from expanding due to pain, e.g. pleurisy.

In these diseases, too, inhalation is promoted by improving the mobility of the thorax and strengthening the corresponding auxiliary muscles. In the case of inflammatory diseases, the focus is on medical pain therapy. The affected people usually breathe quickly and shallowly, as deep breaths are too painful.

.jpg)