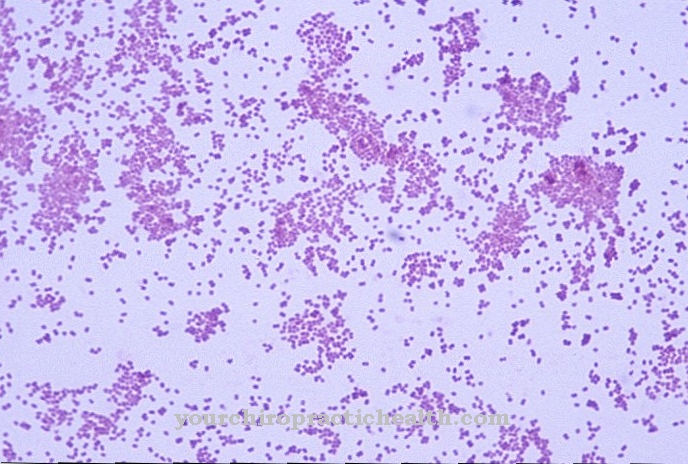

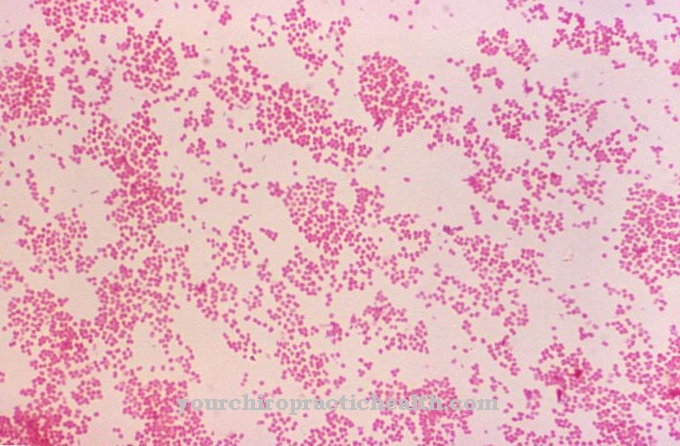

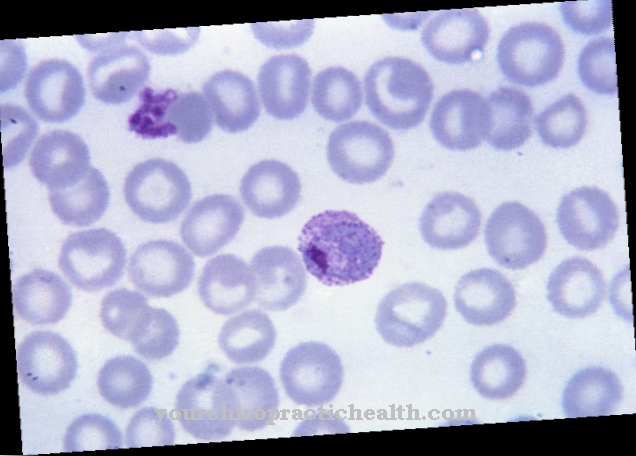

Bacteroides form a genus of obligately anaerobic, uncultivated - and therefore mostly immobile - bacteria that are part of the natural bacterial flora in the human digestive tract and have important functions in certain metabolic processes. The proportion of gram-negative bacteria in the large intestine is particularly high. They utilize complex carbohydrates in a fermentative metabolism, in which, for example, salts and esters of acetic acid are formed as the end product.

What are Bacteroides?

Bacteroides is a genus of gram-negative, pleomorphic, uncultivated bacteria that make up a large part of the natural flora of the digestive tract. They make up a particularly large proportion of the intestinal flora in the mucous membrane of the large intestine, where they predominate in numbers.

These are rod-shaped, gram-negative, mostly immobile, bacteria that can adapt their shape to the habitat in which they are located. The bacteria, which live exclusively anaerobically, take on important functions and tasks that benefit humans. They get their energy from fermentation. They are able to synthesize a number of enzymes that catalytically control the corresponding fermentation processes. Most importantly, they help with the absorption and hydrolysis of otherwise indigestible polysaccharides and proteins. By releasing certain enzymes, they make part of their metabolic capabilities available for the body's own metabolism.

Only a few types of Bacteroides also occur optionally as pathogenic germs. The composition of the intestinal flora has a major influence on the utilization of the food consumed. For example, the proportion of Bacteroides in the intestinal flora of severely overweight people is significantly lower than that of people of normal weight.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

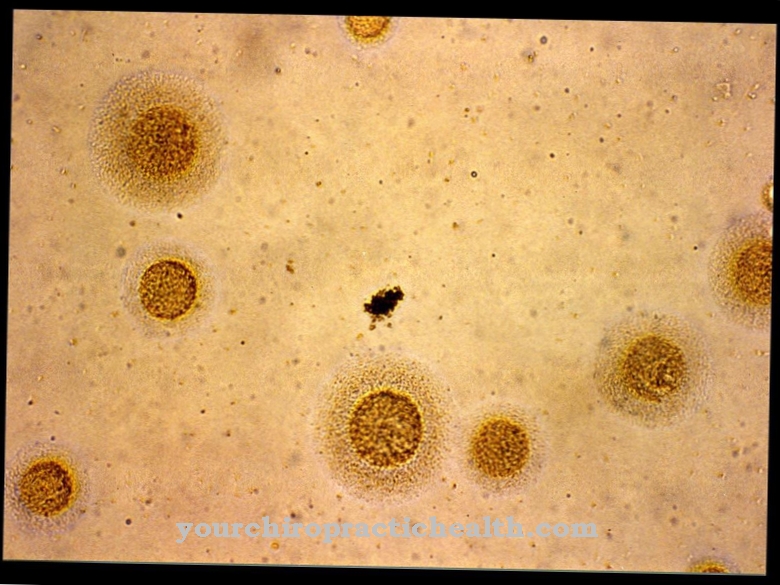

The bacteria of the genus Bacteroides, which live obligately anaerobically, are only slightly pathogenic, and an infection by bacteria of this genus introduced from outside is extremely rare. When the immune system is intact, Bacteroides live symbiotically as a dominant component of the intestinal flora, especially as part of the bacterial association in the large intestine.

It is noticeable that many types of Bacteroides have branched fatty acid chains that are built into their lipid membranes. In addition, some species are able to synthesize sphingolipids. It is a group of substances made up of special lipids that play a role in signal transduction in nerve tissues. Sphingolipids also play an important role in intercellular and intracellular communication.

In rare cases - especially if there is disease-related or artificially induced immunosuppression - endogenously caused infections can occur, i.e. by Bacteroides, which previously colonized the mucous membranes and showed no pathogenicity.

Meaning & function

One of the most important properties and functions of the Bacteroides is not in their pathogenicity, but in the digestive support of humans. Some of the very large protein molecules and polysaccharides, which cannot be broken down in the small intestine due to a lack of enzymes and therefore also not resorbed, go through the "fermentation phase" in the large intestine and can mostly be broken down by the bacteria 's enzymes and then resorbed.

Minerals and trace elements are also isolated from the remaining food pulp with the help of the Bacteroides and made available to the body's metabolism via absorption in the intestinal villi. The bacteria take on an important extension of the digestive possibilities of the body. Without the activity of the Bacteroides or the entire bacterial flora, we could not survive in the long term.

Interestingly, the intestinal flora in newborns and infants consists mainly of bifidobacteria, which are contained in breast milk and have an important protective function. Because the only food source in milk does not contain complex polysaccharides and proteins, Bacteroides are only needed when switching to other food components. It is therefore important to change your diet gradually to avoid digestive problems. The intestinal flora then has enough time to adapt accordingly.

Illnesses & ailments

The strictly anaerobic Bacteroides do not develop any spores. They can hardly survive outside of their habitat because the oxygen in the air has a toxic effect on them. The infections in which Bacteroides are involved are therefore mostly endogenous mixed infections in which facultatively aerobic bacteria ensure the consumption of the oxygen. This type of endogenous infection can occur if, in addition to a weakened immune system, there is, for example, a lesion of the mucous membranes that the germs can use as a gateway.

In the rare cases in which an endogenous infection with (facultative) pathogenic Bacteroides occurs, it is mostly inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) and abscesses on the liver and in the upper abdomen. In principle, the inflammation can originate from those mucous membranes that are colonized with Bacteroides, i.e. from the oral cavity, the intestine or the urogenital tract.

If the rod bacteria enter deeper tissues through appropriate lesions, they will find ideal conditions for their survival. This can lead to festering abscesses and tissue necrosis. Since the infection develops in the absence of air, the dead tissue can develop a very unpleasant odor. In very rare cases, when the necrotic tissue breakdown products get into the bloodstream and the immune system is overwhelmed with the punctual stress, an immediately life-threatening sepsis can develop, which - similar to allergic reactions - corresponds to an excessive immune reaction.

A test for Bacteroides can be carried out via the detection of species-specific organic acids or enzymes using gas chromatography. Diagnosis and detection of the bacterium via the creation of a culture is also reliable, but it must be taken into account that the material with the contained Bacteroides must be kept strictly under airtight conditions, otherwise the pathogens will die.

.jpg)