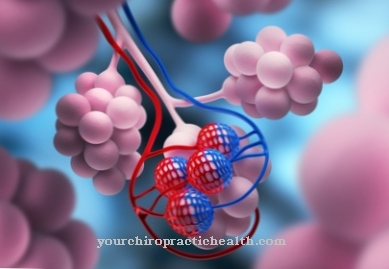

The Expiration is the medical term for a phase of the breathing cycle, more precisely the process of exhaling, during which air is forced out of the lungs. This is usually a passive process of the body, which is caused by the relaxation of the diaphragm and the chest muscles.

What is expiration?

Expiration is a phase of the breathing cycle that is completed by inspiration and several intermediate phases. Expiration is the process of breathing out. This process takes place passively in the idle state. The aim of expiration is to press the used air out of the lungs so that fresh, oxygen-rich air can then flow in.

The diaphragm and chest muscles relax automatically when you breathe out, which forces a large part of the air you breathe out of your lungs. However, expiration can also be voluntary. In this case, the muscles of the respiratory muscles and the auxiliary respiratory muscles are used consciously. In both variants, some air remains in the lungs, which, however, can still be exhaled by consciously exercising the respiratory muscles. The amount of air that remains in the lungs when passively exhaling is called the end-expiratory lung volume.

Function & task

The goal of expiration is to move the carbon dioxide-rich and oxygen-poor air out of the lungs to make room for fresh and oxygen-rich air. The passive relaxation of the diaphragm and the respiratory muscles reduces the size of the chest and with it the lungs. This creates a higher pressure in the lungs compared to the air in the environment, causing the used air to flow out.

If the air has escaped, however, there is negative pressure in the lungs. Due to this condition, fresh, oxygen-rich air can flow back into the lungs in the course of inspiration.

When the diaphragm relaxes, it is pushed upwards and thus against the lungs. This is then pressed together. This process is supported by the respiratory muscles, which are medically called the intercostal muscles. The intercostal muscles include the outer and inner intercostal muscles.

The outer intercostal muscles relax just before expiration, while the inner ones contract. This pulls the chest together and puts slight pressure on the lungs, causing them to shrink too. This is visually visible through a lowering of the chest.

Both muscles or muscle groups are supported in their function by the auxiliary respiratory muscles. This also pulls the chest together and presses the diaphragm upwards against the lungs and thus supports the expiration phase. However, the muscles of the auxiliary exhalation muscles are not in the immediate vicinity of the lungs and therefore do not have a direct effect on the process of exhalation.

The auxiliary exhalation muscles include the abdominal press, part of the abdominal muscles that are also used when coughing or sneezing and when defecating, the erector spine (muscle erector spinae) and the long back muscle (musculus latissimus dorsi).

You can find your medication here

➔ Medication for shortness of breath and lung problemsIllnesses & ailments

Expiration can be made more difficult by various diseases of the respiratory system. Most often, obstructive pulmonary diseases prevent trouble-free expiration. Obstructive disorders of the lungs are characterized by a narrowing or obstruction of the airways, which makes it difficult and slower to exhale. Around 90 percent of all lung diseases are of this type.

In the case of obstructive pulmonary diseases, the air you breathe often flows into the lungs without any problems, but then cannot flow out again unhindered, which means that the lungs quickly overinflate. Often this is due to a narrowing of the lower airways, the bronchi. If, on the other hand, the upper airways in the area of the larynx are narrowed, enough air does not flow into the lungs.

An obstructive pulmonary or respiratory disease can quickly become chronic. It usually begins as chronic bronchitis, which is accompanied by coughing, sputum, shortness of breath and reduced performance, or as pulmonary emphysema, in which the lungs are chronically inflated. Both diseases are usually caused by inhaling harmful substances or smoking. However, there are often genetic predispositions to emphysema as well. Asthma, stenoses in the bronchial tree, glottic edema, tumors or foreign bodies in the airways can also cause obstructive disorders in the lungs.

The second large group of lung diseases are the restrictive disorders. Such disorders limit the expandability of the lungs and thus reduce the exchange volume of the air. As a result, part of the lungs is either still ventilated but no longer supplied with blood, as is the case with pulmonary embolism. Or it is still supplied with blood, but no longer adequately ventilated, which is the case when the bronchi are blocked. With both variants, the blood in the lungs can no longer be adequately enriched with oxygen.

The causes of restrictive disorders of the lungs can be varied. They are often caused by pneumonia, edema or fibrosis, inflammation or air pockets in the pleura, general diseases of the respiratory muscles or also from injuries and deformations in the chest area.

The most common variants of restrictive lung disorders are pulmonary fibrosis, a chronic and progressive inflammation of the lung tissue, and asbestosis, which is caused by exposure to asbestos fibers for too long, mostly for occupational reasons.

.jpg)