The iris, or Iris called, is a pigment-enriched structure in the eye between the cornea and the lens, which surrounds the eye hole (pupil) in the center and serves as a kind of diaphragm for the optimal imaging of objects on the retina. The size of the pupil and thus the incidence of light can be regulated by muscles in the iris.

What is the iris

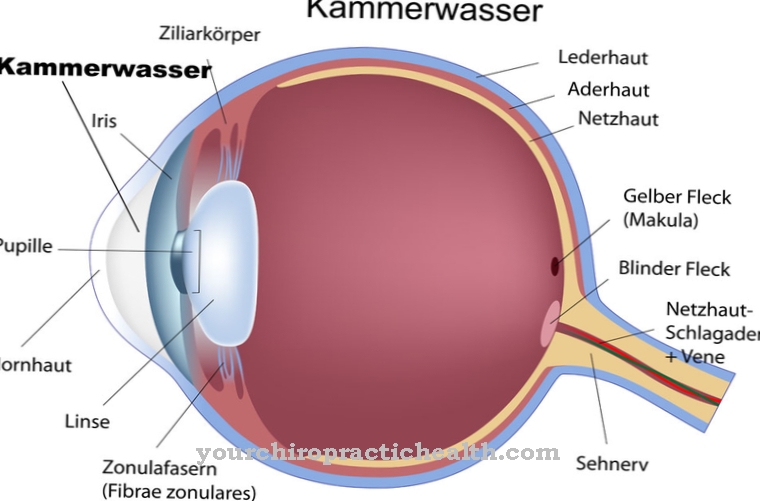

As an opaque barrier, the iris respectively Iris an essential part of the eye. It is the anterior, visible part of the choroid and lies parallel to the frontal plane behind the cornea and in front of the lens. It thus divides the eye chamber between the two structures into an anterior and posterior area. The iris is fixed at its edges, the iris root, with the ciliary body. In its center it leaves an opening, the pupil, free through which light can fall and hit the retina further behind.

Except when there is a genetic defect (albinism), the iris has a blue, green or brown color with all color transitions in humans. This phenomenon is due to the varying density of pigments. A high pigment density colors the iris brown, while a lower pigment density turns it light. Ontogenetically, the individual components of the iris are either of mesodermal or ectodermal origin.

Anatomy & structure

In the histological cross-section, the iris consists of two main layers. The so-called stroma follows the front boundary line - a fibrous layer permeated by blood vessels and nerves, in which pigments of different densities are embedded and which determine the individual's eye color. In the stroma there is also the Sphincter pupillae musclewhose muscle cells run in a ring around the edge of the eye hole. Behind this fibrovascular layer lies a thick epithelial layer consisting of two layers of cells, the pigment sheet (Pars iridica retinae), which is also characterized by a strong build-up of pigment and is connected to muscles. These are dilator muscles (Dilator pupillae muscle), which are arranged radially as basal extensions of the pigment sheet and, together with the sphincter muscle (sphincter muscle), ensure good image sharpness.

When viewed from the front, the iris can be divided into two regions. The pupillary part is formed by the innermost area of the iris, which at the same time defines the edge of the pupil. The rest of the iris belongs to the ciliary part. Both regions are separated from each other by the iris ruff (collarette), where the sphincter muscle intersects with the dilator muscles. From this thickest point, the depth of the iris tapers noticeably towards the edges.

Function & tasks

The iris is essential for optimal vision. Due to the continuously changing lighting conditions, constant compensation must be provided by the eye in order to be able to perceive the environment razor-sharp. Similar to the aperture of a camera, the eye is adjusted via the iris, which influences the size of the pupil through involuntary muscle contractions and thus regulates the amount of incident light.

This is the only way to ensure a sharp image of objects on the retina. Through the influence of the iris on the width of the eye hole, damage to the retina from excessive light radiation can also be avoided, as occurs in some clinical pictures.

In addition to the regulation of the pupil size, the opacity of the iris is essential for the sharp representation of objects, which is what ensures the functionality of the iris as a diaphragm. The scattered light hitting the eye is prevented from further penetrating the retina by the dense color deposition in the pigment sheet, so that the incidence of light is limited to the eye hole. The narrowing of the pupil (miosis) occurs through contraction of the sphincter muscle in a circular movement. Its counterpart are dilator muscles, which cause the expansion (mydriasis) by a radial contraction of the iris and folds it.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines for eye infectionsIllnesses & ailments

One of the most common diseases of the iris is iritis or iridocyclitis. In both cases there is inflammation of the iris or the ciliary body, which leads to blurred vision and increased sensitivity to light. Failure to treat the infection with antibiotics in a timely manner can lead to severe vision loss or total blindness. Cataracts or glaucoma can form as a result.

Genetic defects such as aniridia also cause problems for those affected. In this type of disease, the iris is completely absent or so underdeveloped that only a small, rudimentary margin is present. In both cases the incidence of light is too high, which seriously affects the eyesight.

However, complaints can also cause minor damage, such as small holes in the iris (coloboma). These lead to the representation of shadows or double images. This phenomenon is caused either by traumatic events or genetic deviations.

Further diseases of the iris are malignant melanomas, which are usually discovered quickly due to their good visibility and treated immediately. In the early stages, iris removal is sufficient for treatment. Proton therapy is used with good success in melanomas detected later.

In albinism, individuals suffer from a complete loss of color pigments in the body. The iris, which is normally colored, is now translucent and thus loses its function as a diaphragm, since light also penetrates through it. This leads to the glare of the visual cells and impaired visual function even in infancy and toddlerhood.