In the case of a fracture of a bone, a fracture heals callus. This tissue ossifies over time and ensures a complete restoration of function and stability. Under certain conditions, however, fracture healing can be pathological and involve various complications.

What is the callus?

The name callus is derived from the Latin word callus ("callus", "thick skin"). This term stands for newly formed bone tissue after a fracture. At the fracture site, scar tissue forms first, which bridges the fracture gap. The callus gradually ossifies and forms new bone tissue. The terms are often synonymous with this Bone callus or ‘‘ ‘fracture callus‘ ‘‘ used.

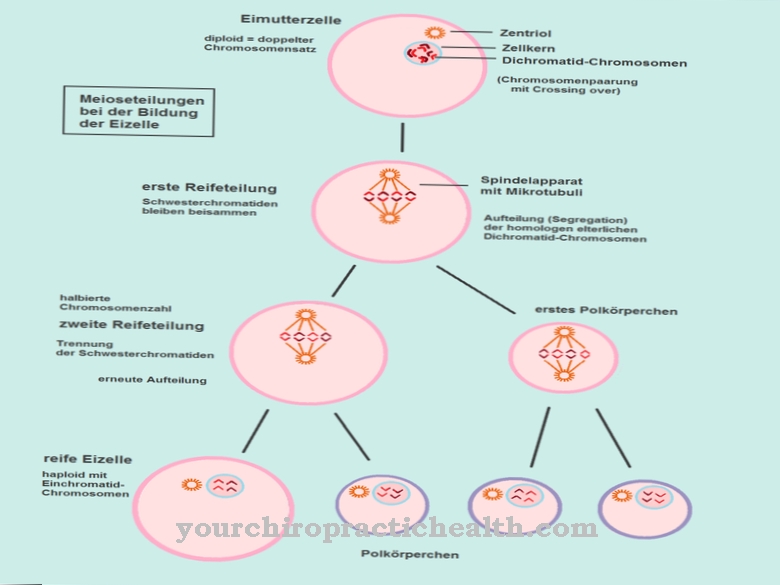

In bone healing, a distinction is made between a primary and a secondary healing process. Callus formation occurs only with secondary bone formation, which can be shown radiologically after several days to weeks.

Depending on the phase of bone healing, different forms of callus are distinguished: Callus made from pure connective tissue is called myelogenic, periosteal or endosteal callus, depending on the type of connective tissue that forms. If this solidifies through the accumulation of lime, it is a temporary callus or intermediate callus. Shortly before complete healing, bony callus is created, which is modeled and broken down over time.

Anatomy & structure

Depending on the phase of bone healing, the callus is formed from different tissue. Fibro-cartilaginous callus consists of tight connective and cartilage tissue and provisionally connects the ends of the fracture. This tissue is converted into braided bone in the course of endochondral ossification.

In contrast to lamellar bones, this is an immature form of bone in which the collagen fibers of the bone matrix do not run in a specific direction, but criss-cross. Only in the last stage of the healing process are the fibers of the bone matrix aligned in parallel so that a resilient lamellar bone is created. The initially cartilage- and connective-tissue-like callus is completely ossified at this point.

Function & tasks

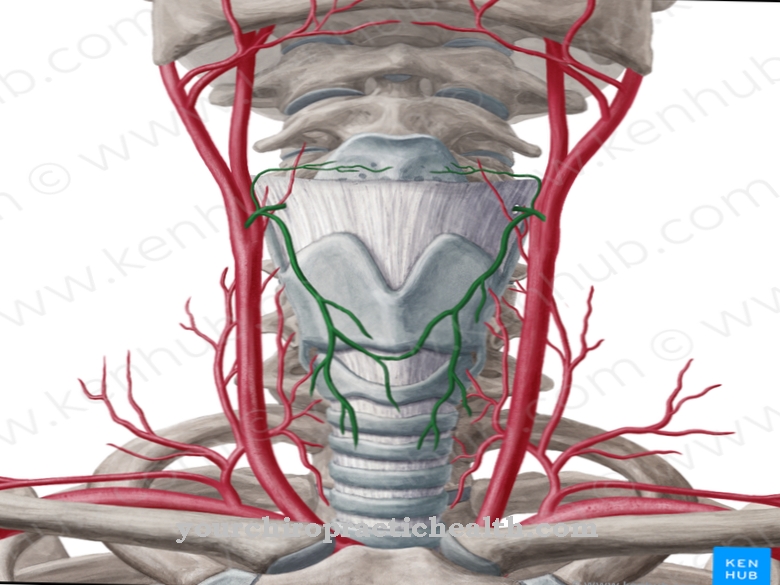

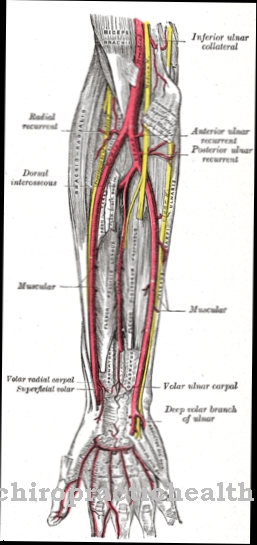

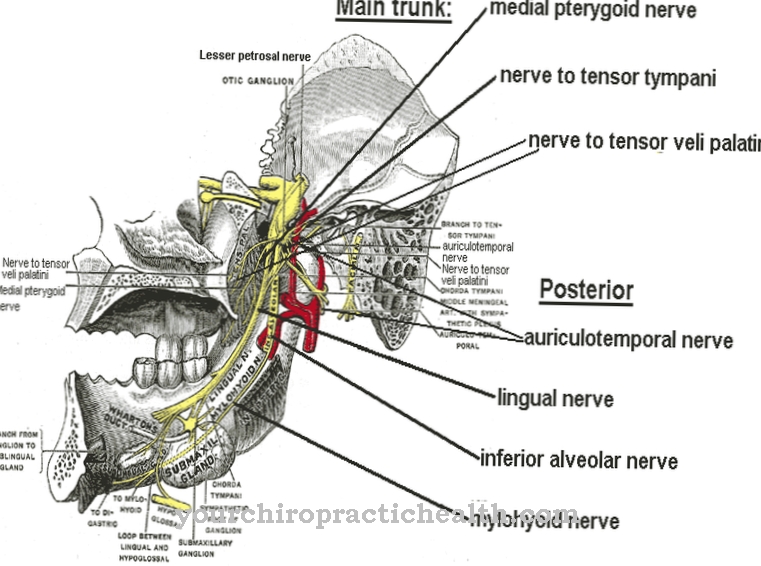

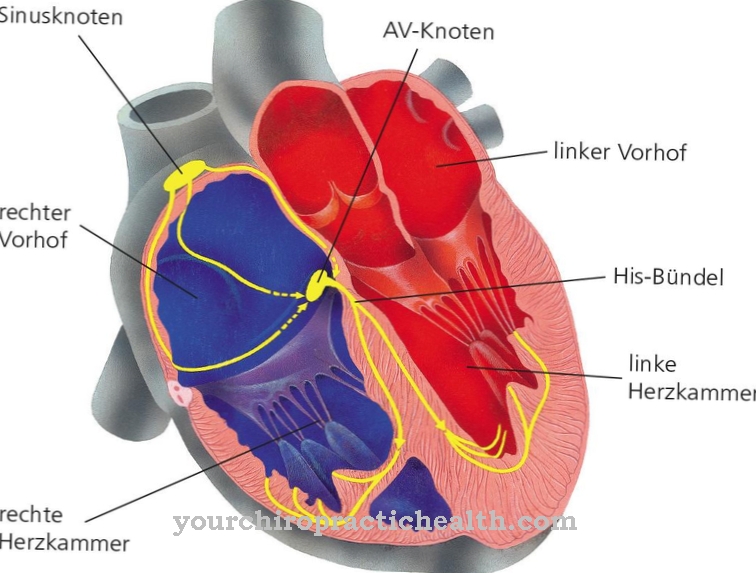

A distinction is made between primary and secondary bone healing. Primary bone healing occurs through the Haversian canals. These are channels in the bone cortex that contain blood vessels and nerve fibers. The task of the Haversian canals is to supply the bone with nutrients and to transmit stimuli.

If the width of the fracture gap is less than one millimeter and the outer periosteum is still intact, capillary-rich connective tissue can grow into the fracture gap through the Haversian canals. Cells from the inner and outer periosteum are stored and remodeled in such a way that the bones can withstand stress again after about three weeks.

Secondary fracture healing occurs when the gap between the bone parts is too large or the ends of the fracture are slightly displaced. Even if movement between the fracture parts is possible, secondary healing with callus formation is necessary.

Secondary fracture healing takes place in five phases. First, the bones are subjected to force, which destroys the bone structure and leads to the formation of a hematoma (injury phase). In the subsequent inflammatory or inflammatory phase, macrophages, mast cells and granulocytes invade the hematoma. At the same time as the hematoma is broken down, bone-forming cells are built up.

After four to six weeks, the inflammation subsides and the granulation phase occurs. A soft callus is now formed from fibroblasts, collagen and capillaries. New bone tissue is built up in the area of the periosteum. In the fourth phase (callus hardening) the soft callus hardens and the newly formed tissue mineralizes. After about three to four months, the physiological resilience is restored. In the last phase (remodeling phase) the original bone structure with the medullary canal and Haversian canals for the nutrient supply is restored.

Secondary bone healing can take six months to two years. The length of time depends on various factors such as the type of bone or the age of the person affected.

Diseases

Bone healing is not always physiological. Disorders of the healing process can occur due to a lack of oxygen and nutrient-rich blood. In addition, a normal anatomical position of the bone parts with close contact to one another is required. The mobility of the two parts should be reduced to a minimum, and permanent compression forces accelerate fracture healing.

Open fractures can delay the healing process or make it impossible if it results in infection of the bone or surrounding tissue. Regular nicotine consumption and circulatory-damaging diseases such as diabetes or osteoporosis also have a negative effect on fracture healing.

If one or more of these conditions are met, a pathological course can occur. Failure to form bony callus within the regular time is called delayed fracture healing. If this lasts longer than six months, pseudarthrosis can occur. This is an additional, pathological joint in the bone. The reason for this is usually insufficient immobilization. However, not only a lack of callus formation, but also excessive callus formation can lead to the occurrence of pseudarthrosis. This takes place through excessive compression of the fracture points, the cause of which is also a lack of immobilization.

If the fracture is in or in the vicinity of a joint, the movement may be restricted in the course of healing and, as a result, the affected joint may contract. In very rare cases, due to the formation of callus, nerves and vessels close to the bone are damaged by compression.