The Coupling ability coordinates partial body movements within the framework of an overall movement or an action goal. This learned skill is one of seven coordinative skills. Coupling skills can be trained, but can be affected by central nervous disorders.

What is the coupling ability?

The expression “coupling ability” comes from sports medicine and describes the sports motor skills for the targeted coordination of partial body movements. This ability is one of the so-called coordinative skills.

Together with the ability to rhythmically, the ability to react, the ability to orientate and the ability to balance and adapt, the ability to connect forms an important basis for sporting training units.

The relationship structure of the individual coordinative skills is usually trained and analyzed in relation to a specific sport and its movements. The ability to connect in a sport determines to a certain extent a person's ability to learn and their potential. In this context, however, it is difficult to see it in isolation from the other coordination skills.

A distinction must be made between the coordinative abilities of sports medicine and the conditional abilities. These include strength, endurance, speed and flexibility.

Function & task

Like all other coordinative skills, the ability to connect is relevant for any type of movement. Without the coordination skills, neither the gross motor skills nor the fine motor skills can function.

In particular, the ability to connect enables the spatial, temporal and dynamic coordination of partial body movements to achieve a specific action goal. Partial body movements are coordinated into a targeted overall movement.

All coordinative skills are based on the interaction of the central nervous system, the sensory perception system and the muscular system. Although coordinated movement and thus also the interaction of the individual systems is relevant in everyday life, it is all the more important for sport. Movement sequences in sport usually require even more precision, speed and coordination than everyday movements.

The ability to connect is relevant for every sport. In table tennis, for example, when the coupling ability is optimal, one speaks of a clean striking technique: footwork, torso work and arm pull play together perfectly. In football, for example, the ability to connect can be clearly seen in the goalkeeper. He coordinates the run-up, the jump and the arm movements to achieve his goal of movement and to catch the ball. The jump and belaying require precise coordination of manual work and leg guidance.

The ability to couple for gymnastics and apparatus gymnastics is perhaps even more relevant. In gymnastics, for example, running is combined with jumps and arm circles with or without equipment. In apparatus gymnastics, the leg-torso and arm-torso angles are constantly changed in a way that is appropriate and coordinated. Coupling is also essential for dance. When dancing, for example, the arms can be moved on different levels or perform symmetrical or less symmetrical figures in asynchronous movements.

The objective of action differs with the type of movement, but the ability to connect still remains a requirement. For this reason, a person's coordinative skills generally say something about their overall ability to learn sports techniques. An athlete in training has well-trained coordination skills. Therefore it is usually easier for him to learn another sport than an untrained person, although the coordinative processes of his sport do not match the new sport to be learned.

Illnesses & ailments

Like all other coordinative skills, the ability to connect is not innate. It is learned, consolidated and can be further developed. Especially between the ages of seven and 12, the coordinative skills learned up to that point are consolidated.

Because these abilities are not anatomically given abilities from the outset, complaints relating to the ability to connect need not necessarily include disease value. The ability to connect differs from person to person and is, among other things, related to childhood. If a child does not move enough, it will later have a harder time coupling partial movements than an active child.

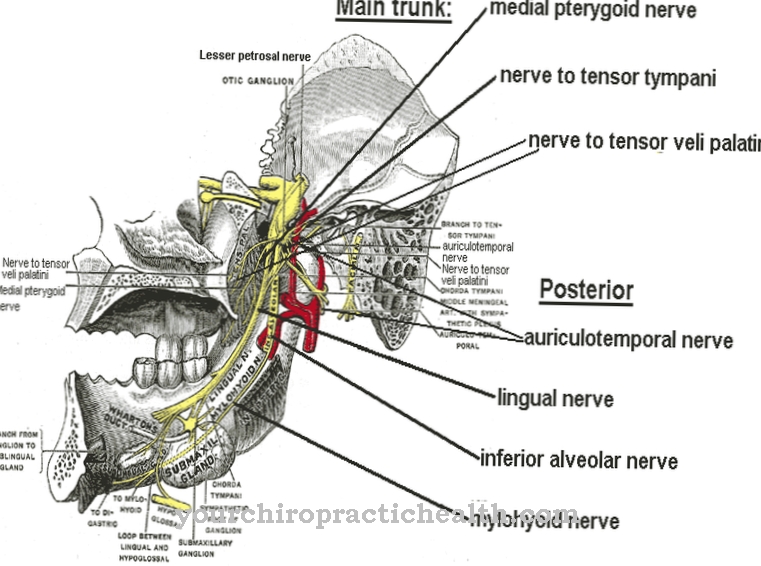

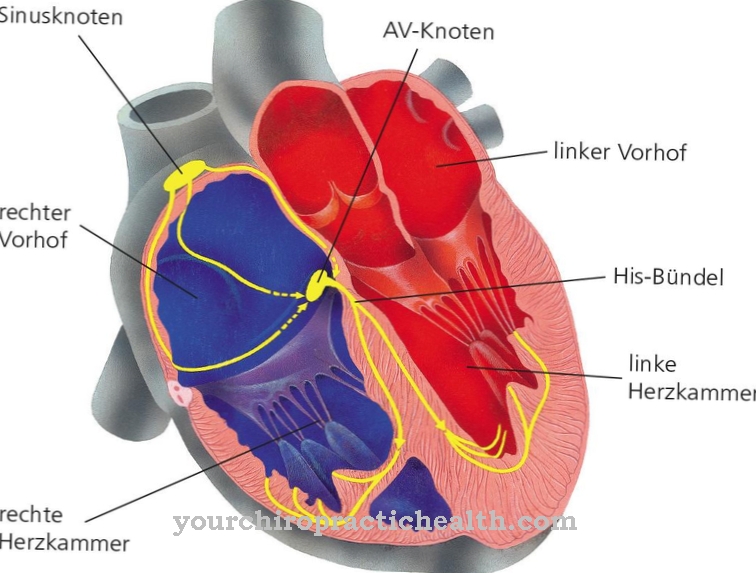

On the other hand, a suddenly disturbed coupling ability can be an indication of a central nervous or muscular structure. The planning of movements takes place in the motor areas of the cerebral cortex. If these areas are affected by inflammation, bleeding, masses or trauma, movement planning is no longer possible. This becomes noticeable in a loss or at least an impairment of the coupling ability.

From the motor areas, the movement plan reaches the cerebellum and the basal ganglia. Even if these areas of the brain are affected by diseases, the ability to connect changes. The cerebellum, for example, only makes fluid, targeted movements possible.

The muscle contractions in an extremity must be precisely coordinated for a fluid, targeted movement, and this coordination is carried out by the cerebellum. The basal ganglia, in turn, are responsible for the intensity and direction of movements. Only from here do the movement commands from the brain reach the nerves of the muscles.

Damage to these peripheral nerves can also affect the ability to connect. Since the ability to connect corresponds to spatial, temporal and dynamic coordination of movements, general concentration disorders, disorientation or psychological problems can also impair this ability.

.jpg)