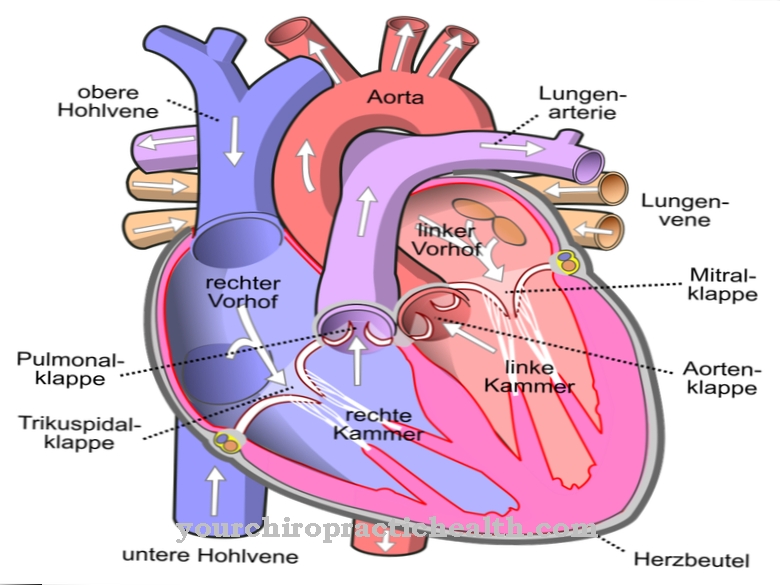

The two heart valves, which connect the left atrium with the left ventricle and the right atrium with the right ventricle, are called for anatomical reasons Sail flaps designated. The two leaflet valves function according to the non-return principle and, together with the other two heart valves, which are designed as so-called pocket valves, ensure an orderly blood circulation that is kept going by the individual heartbeat phases.

What is the sail flap?

Two of the four heart valves are designed as so-called sail valves. In their double function as inlet and outlet valves, they each form the connection between the left atrium (atrium) and the left chamber (ventricle) or the right atrium and the right chamber.

From a functional point of view, the two flaps are also called Atrioventricular valves or AV valves designated. The leaflet valve in the right half of the heart has three leaflets (cuspis), as its name, tricuspid valve, already indicates. Its counterpart in the left half of the heart has only two cusps and is called the mitral valve or bicuspid valve. The name mitral valve goes back to its resemblance to a bishop's cap, the miter.

The two leaflet valves open during the relaxation phase of the ventricles (diastole), which occurs almost simultaneously with the tension phase of the atria. As a result, the blood flows from the atria into the chambers and fills them. During the subsequent tension phase of the chambers (systole), the two leaflet valves close, so that the blood is pumped from the right chamber into the pulmonary artery. At the same time, the left ventricle contracts and pumps the blood into the aorta, the body artery from which all arteries of the great blood circulation branch off.

Anatomy & structure

Because of their function, the two leaflet valves are also known as atrioventricular valves or AV valves for short. The AV valve of the right half of the heart consists of three leaflets, called cuspis, which gave it the name tricuspid valve.

The leaflet valve of the left half of the heart consists of only two leaflets, from which its name is derived from the bicuspid valve. However, it is better known under the name mitral valve because its appearance is somewhat reminiscent of the miter, the headgear of the Catholic bishops. The edges of the individual cusps are connected to papillary muscles by partially branched tendon threads, the chordae tendineae. These are small muscular elevations that arise from the heart muscles of the ventricles and have the ability to contract, so that the tendon threads are tightened and prevent penetration into the corresponding atrium when the leaflet valves are closed.

Since each leaflet is connected to its “own” papillary muscle, three of them are in the right and two in the left ventricle. The sails each consist of four layers. A layer of endothelial cells, which are formed from the endocardium of the atrium or the chamber, serves as the final layer. Underneath there is a thin layer of connective tissue cells, which also contains smooth muscle cells on the side facing the atrium. Under the connective tissue layer is the sponge layer with embedded collagen fibers and elastic fibers.

Function & tasks

The valve function of the leaflet valves is to regulate the blood flow between the left atrium and the left chamber or between the right atrium and the right chamber. During the tension phase of the atria, which coincides almost simultaneously with the relaxation phase (diastole) of the chambers, the leaflet valves are open, so that both chambers fill with blood.

During the subsequent tension phase (systole) of the chambers, the cuspid valves close - similar to a check valve - and thus prevent the blood from flowing back into the respective atria. So that the cusps do not break through into the atria due to the pressure build-up in the chambers, the papillary muscles also contract, so that the tightened tendon threads virtually “hold” the cusps.

The closed leaflet flaps enable the right chamber to pump the oxygen-poor and carbon dioxide-enriched blood from the circulatory system into the pulmonary artery and the left chamber to pump oxygen-rich blood from the pulmonary system into the aorta, the large body artery and thus into the circulatory system. An orderly blood flow does not only require the proper functioning of the two leaflet valves, but also that of the two pocket valves, which are located in the left chamber at the aortic entrance and in the right chamber at the entrance to the pulmonary artery.

Diseases

In principle, two different functional errors can occur on both wing flaps. If, during the opening phase, one of the leaflet valves opens an insufficiently large opening for the blood flow from the respective atrium into the chamber, there is a stenosis with more or less severe effects.

If a closed leaflet valve does not close completely during the systole of the ventricles, there is valve insufficiency, which can be divided into different insufficiency classes depending on its severity. A part of the blood flows back into the corresponding antechamber, so that the cardiac output is restricted by the "promotion" in the circle. Depending on the severity of the valve insufficiency, there is a noticeable to serious loss of performance and shortness of breath. In special cases, a combination of both valve errors can occur on the same valve.

The valve defects that occur can be acquired or exist from birth due to a genetic defect. An acquired valve defect in one of the leaflet valves is usually due to endocarditis, an inflammation of the inner lining of the heart, because the inflamed epithelial layer continues on the leaflets of the valves. As a rule, endocarditis results in scarring or sticking of the cusps, which results in stenosis or insufficiency or even a combination of both functional disorders.

An inherited valve defect can cause similar symptoms. In rare cases, for example, the tricuspid valve is completely absent at birth, which leads to dangerous mixing of blood from the two atria through the then still open foramen ovalis, which connects the two atria prenatally.

.jpg)

.jpg)