Trypsinogen is a zymogen or a proenzyme. Proenzymes are inactive precursors to enzymes. Trypsinogen is the inactive precursor of the digestive enzyme trypsin.

What is trypsinogen?

Trypsinogen is a so-called proenzyme. A proenzyme is a precursor to an enzyme. However, this preliminary stage is inactive and must first be activated. Activation takes place through proteases, the enzyme itself or depending on pH values or chemicals.

In its active form, the trypsinogen is called trypsin. It plays an important role in digestion and especially in the breakdown of proteins. A lack of trypsinogen can lead to digestive disorders.

Function, effect & tasks

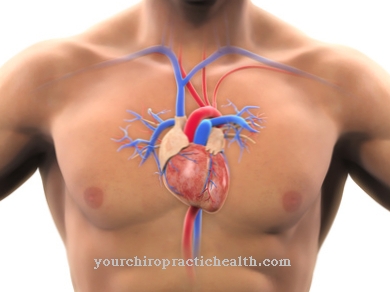

Trypsinogen is produced by the pancreas (pancreas). Production takes place in the exocrine part of the pancreas. The pancreas is the most important digestive gland in the human body. Together with the trypsinogen, further digestive enzymes and proenzymes are produced here.

Trypsinogen belongs together with chymotrypsinogen and elastase to the protein-splitting enzymes. They are also known as proteases. These substances, together with the enzymes for carbohydrate splitting, the enzymes for splitting fat and a bicarbonate-containing liquid, form the pancreatic secretion. The pancreas produces about one and a half liters of this digestive secretion per day.

The exact amount and composition of the secretion released depends on the food consumed. The more protein was eaten, the higher the proportion of protein-splitting enzymes, for example. The release of trypsinogen is also controlled by parasympathetic and endocrine mechanisms. The hormones secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK) play a decisive role here.

Education, occurrence, properties & optimal values

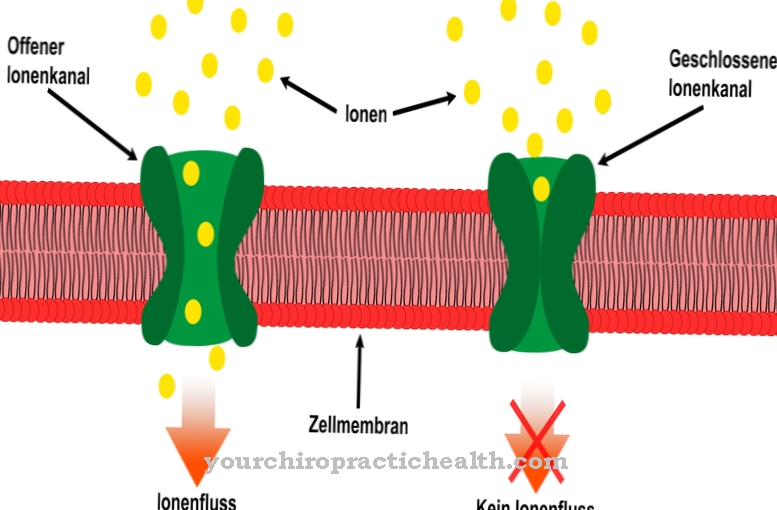

Trypsinogen, together with the remaining pancreatic secretion, enters the large pancreatic duct via the pancreatic ducts. This opens into the small intestine. The trypsinogen is converted into its active form in the small intestine. For this purpose, a hexapeptide is split off from the proenzyme by an enterokinase. This creates the active digestive enzyme trypsin.

Trypsin is an endopeptidase and breaks down proteins. If you look closely, depending on the intestinal region, trypsin splits protein bonds with the basic amino acids lysine, arginine and cysteine. Trypsin works most effectively under basic conditions, i.e. at a pH value between seven and eight. These conditions are guaranteed by the basic pancreatic secretion in the small intestine. But trypsin has another task. It acts as an activator for other proenzymes. For example, it converts the proenzyme chymotrypsinogen into the active form chymotrypsin.

The question now remains as to why the pancreas does not produce trypsin directly, but rather an inactive precursor. The answer is pretty simple. If active digestive enzymes were already circulating in the pancreas, they would begin to work in the pancreas as well. The pancreas would digest itself. This process is also known as autodigestion. It can be found, for example, in acute pancreatitis.

Diseases & Disorders

Acute pancreatitis is inflammation of the pancreas. Gallstones are the most common cause of such dangerous inflammation. When these migrate from the gallbladder through the biliary tract, they often get stuck at the confluence with the small intestine.

In many people, the bile duct opens into the small intestine together with the pancreatic duct, so that if the bile duct is relocated at this point, the pancreatic duct is automatically relocated. As a result of this relocation, the digestive secretion of the pancreas backs up in the small passages. For reasons that are not yet fully understood, the proenzymes are activated early. Trypsinogen becomes trypsin, and chymotrypsinogen becomes chymotrypsin. The digestive enzymes do their work in the pancreas and digest the pancreatic tissue. This leads to tissue breakdown and severe inflammation. Acute pancreatitis begins suddenly with severe pain in the upper abdomen.

The pain can radiate into the back in a belt shape and be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Air accumulates in the abdomen, which in connection with the characteristic defense tension leads to the phenomenon of the rubber belly. If the walls of the pancreas are so badly damaged that pancreatic secretion escapes into the abdominal cavity, other organs can also develop. Sepsis can occur. In severe cases, blue-green spots can be observed in the area of the navel (Cullen's sign) or in the area of the flanks (Gray-Turner sign). An increased serum concentration of trypsin can be detected in the laboratory.

In the case of pancreatic insufficiency, on the other hand, there is a lack of trypsinogen and thus also a lack of trypsin. The other digestive enzymes and proenzymes are also affected by the loss of function of the pancreas. Pancreatic insufficiency usually arises from a previous inflammation. Chronic pancreatitis in particular plays a role here. More than 80% of it is the result of chronic alcohol abuse.

Pancreatic insufficiencies can also occur, for example, in cystic fibrosis. Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease that affects the pancreas, lungs, liver, and intestines. The glands of these organs are particularly affected. The pancreatic secretion of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis is significantly more viscous than in healthy people. It clogs the pancreatic ducts, causing inflammation.

The lack of digestive enzymes in pancreatic insufficiency primarily causes digestive problems. Those affected suffer from gas, bloating and diarrhea. So-called fat stools, which are caused by insufficient fat digestion, are also typical. The stool will appear greasy, shiny, and smelly. Weight loss despite unchanged or even increased food intake is also characteristic.