Antigens stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies. Antigens are mostly specific proteins on the surface of bacteria or viruses. In autoimmune diseases, the recognition of antigens is disturbed and the body's own tissue is fought as a foreign antigen.

What are antigens?

Antigens are the substances against which the lymphocytes of the immune system make antibodies. Lymphocyte receptors and antibodies can specifically bind to antigens and thus stimulate antibody production and protective immune reactions. A distinction must be made between antigenicity and immunogenicity.

Antigenicity describes the ability to bind to a specific antibody. Immunogenicity, on the other hand, means the ability to induce a specific immune response. Medicine differentiates between full antigens and half antigens. Complete antigens independently trigger the formation of certain antibodies. Half-antigens or haptens are not capable of this. To do this, you need a so-called carrier, i.e. a protein body that turns them into a full antigen.

Anatomy & structure

As a rule, antigens are proteins or otherwise complex molecules. More rarely, they also correspond to carbohydrates or lipids. Smaller molecules usually do not trigger immune reactions on their own and can therefore not be called antigens.

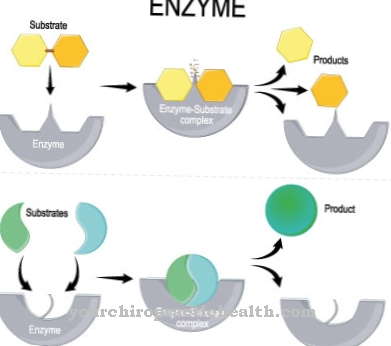

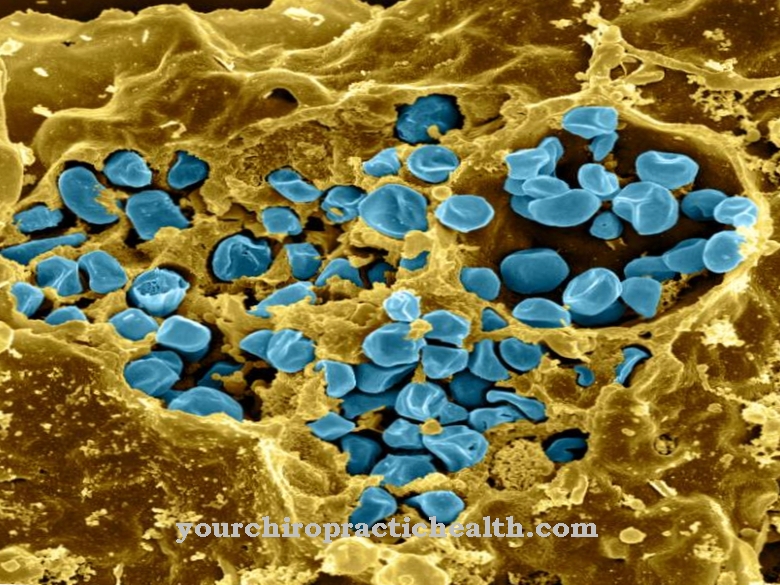

An antigen is usually made up of antigenic substructures. These substructures are also called determinants or epitopes. They either bind to B-cell receptors, to T-cell receptors or directly to antibodies. B-cell receptors and antibodies recognize and bind the antigens on the surface of foreign bodies that have entered.

These antigens have a three-dimensional structure, which is one of the most important identifying features for the B-cell receptors and antibodies. T cell receptors recognize antigens from denatured peptide sequences of around ten amino acids. These amino acids are taken up by antigen presenting cells. Together with the MHC molecules, they are presented on the surface.

Function & tasks

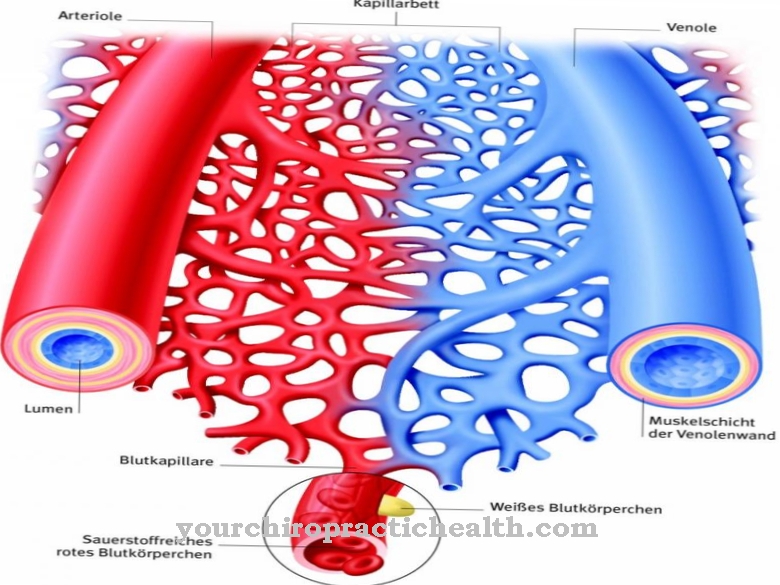

The human immune system has genetically encoded receptors for certain substances. So it can recognize many exogenous substances as danger and fight them through immune reactions. The organism does not have hereditary-coded receptors against every type of substance. The antigen recognition by the lymphocytes protects the organism in this regard from foreign substances for which there are no hereditary coded receptors.

The binding of a lymphocyte to foreign substances triggers an adaptive immune response. Antigens initiate the formation of different antibodies. These antibodies bind with the present epitope and contain the dangers. The recognition of exogenous antigens enables the immune system to target intruders such as viruses without damaging the body's own cells. While hereditary-coded receptors of the immune system can assess certain substances as dangerous from the outset, the immune response in the context of antigen recognition is linked, so to speak, to a learning process of the immune system.

As soon as the body has come into contact with the antigen of a certain bacterium or virus, specific antibodies are available for this substance, which help in combating the supposed threat the next time the antigen comes into contact. The human body also contains antigens. The immune system develops a tolerance towards these endogenous antigens and therefore recognizes them as harmless. The glycoprotein structures on the cell surface of human tissue are different in each person.

The tolerance can therefore develop in a specific and differentiated manner to one's own antibodies. The body tissue of another person is then still recognized as a foreign antigen and combated. This makes transplants difficult, for example. The immune system of a transplant recipient often recognizes the transplanted tissue as a nonself antigen against which it develops specific antibodies. For this reason, in the case of transplants, attention must always be paid to the compatibility of the tissue. In the meantime, transplant patients are also given immunosuppressants that block the process described.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines to strengthen the defense and immune systemDiseases

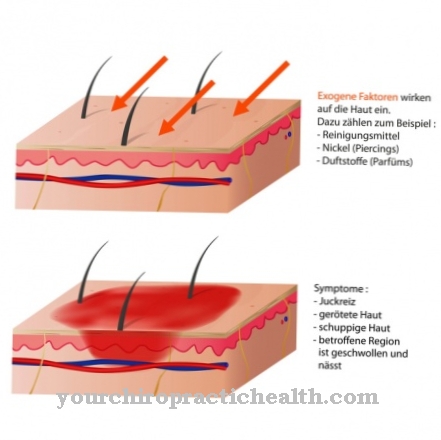

Allergies are an overreaction to certain antigens. The immune system assesses exogenous antigens in the context of allergic diseases as more dangerous than they actually are. Disrupted antigen recognition is also present in autoimmune diseases. In these diseases, an immune response against the body's own antigens is set in motion.

The immune system is normally tolerant of the body's own substances. With autoimmune diseases, however, this tolerance breaks down. To date, the exact cause of autoimmune diseases is unclear. The sequestration theory assumes that many of the body's own antigens were not in the immediate vicinity of these immune cells during the development of tolerance of the immune cells. These endogenous antigens cannot be recognized as endogenous if at some point there is direct contact.

If, for example, an injury leads to such direct contact between the immune cells and the body's own antigens, then they are attacked as foreign antigens. Other theories assume that the cause of the attack by endogenous substances is a change in the endogenous antigens in the context of certain viral infections or drugs. Whichever theory is correct: In any case, faulty antigen recognition is the basis of autoimmune diseases.

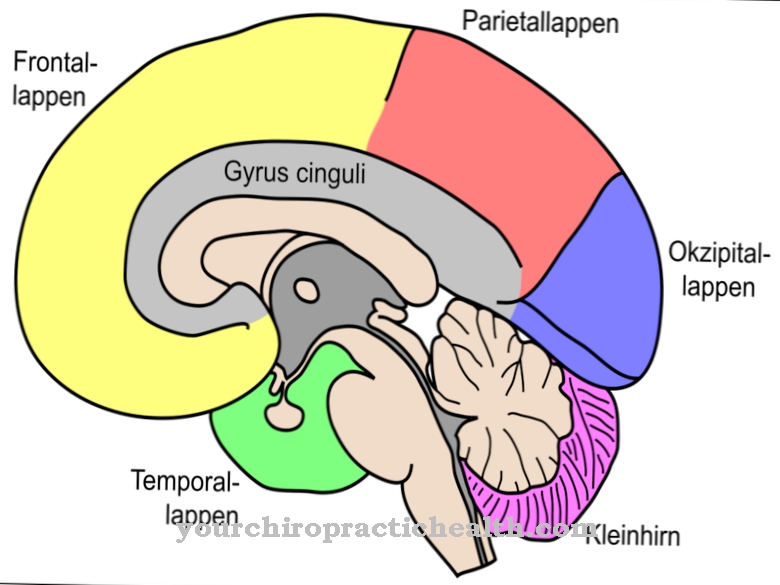

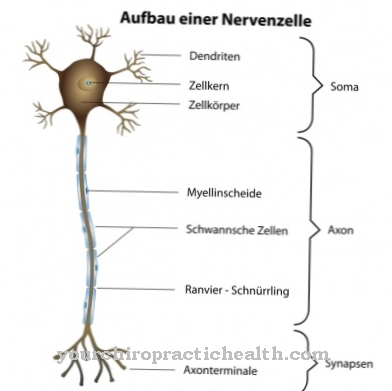

A well-known example of such a disease is the inflammatory disease multiple sclerosis, in which the own immune system attacks tissues of the central nervous system and thus triggers destructive inflammation in the brain or spinal cord. The reverse case also involves dangers. For example, the body can develop a tolerance to antigens that are foreign to the body. The immune system then no longer attacks these tolerated antigens and thus exposes the organism to great danger.

.jpg)