The Appendix vermiformis is an appendage of the appendix that is prone to acute inflammation. It also becomes colloquial Appendix called. More recent research results indicate an immunoregulatory function of the organ, which was previously classified as largely functionless.

What is the vermiform appendix?

The appendix vermiformis (appendix of the appendix) is a protuberance consisting largely of lymphatic tissue with an average length of 10 cm and a diameter of 0.5 mm, which opens into the appendix (caecum) via a flap-shaped mucous membrane fold, the so-called Gerlach valve.

The appendix is popularly often incorrectly referred to as the appendix. The vermiform appendix is located in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen as the point of departure of the caecum below the ileocecal valve (valva ileocaecalis), the functional closure between the large and small intestines.

Anatomy & structure

The vermiform appendix is extremely variable in shape, size and location, but is usually located retrocecally ("behind the caecum") ascending or descending. The three tänien of the large intestine continue on the appendix as a closed longitudinal muscle layer.

Overall, the appendix vermiformis consists of the following tissue layers (from inside to outside): a mucous membrane (tunica mucosa), a connective tissue layer between the mucous membrane and muscle layer (tela submucosa), a fine tissue layer with smooth muscle cells (tunica muscularis) and a serous layer of skin (tunica) serosa). The serosa surrounding the organ merges into the mesoappendix (mesenteriolum) at the point of attachment, which leads to the supplying blood vessels (appendicular artery, appendicular vein).

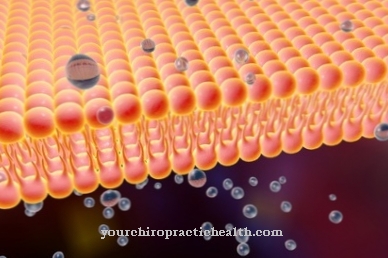

Peyer's plaques are located in the tela submucosa and tunica mucosa. These lymph follicle collections protrude into the appendix lumen like a dome in some areas. Instead of the usual villi and crypts, M cells are found here. These conduct antigens to the lymph follicles and trigger an immune response.

Function & tasks

The function of the vermiform appendix has been discussed for a long time. Despite evidence to the contrary, until a few years ago it was assumed that the appendix was merely a functionless remnant of evolutionary development. Rather, it is now assumed that this lymphatic organ has an immunoregulatory function and can be assigned to the so-called GALT (gut-associated lymphoid tissue), the immune system of the intestine.

The exact function has not yet been clearly clarified. In the entire gastrointestinal tract, the intestinal-associated lymphatic tissue consists of aggregated lymph follicles (Peyer's plaques) which, as colonies of B-lymphocytes, serve to multiply and differentiate from B-lymphocytes into antigen-producing plasma cells. As part of the acquired immune system, Peyer's plaques play an important role in the defense against infections and the processing of immunologically relevant information.

In addition, recent studies indicate that useful bacteria of the natural intestinal flora in the case of diarrheal diseases, together with molecules of the immune system in the appendix vermiformis, are protected from diarrhea-related flushing and are supplied with antibodies by the surrounding lymphatic system. The appendix acts accordingly as a kind of "safe house" (safe hiding place). In the convalescence phase, the bacteria that survive in this way can colonize the intestine again and displace the germs still there. This function is particularly important in areas with poor hygienic context conditions. In developed countries, the frequently performed appendectomy (removal of the appendix as a result of inflammation) has no effects on the health of those affected according to previous knowledge.

Illnesses & ailments

Especially in children from elementary school age and young adults, strands of scars, indigestible food components (e.g. fruit pits) or fecal stones can lead to a blockage of the appendix lumen. The accumulated secretion damages the wall of the appendix and provides an optimal breeding ground for bacterial pathogens that migrate either via the bloodstream or from the intestinal flora (intestinal infections), multiply and cause acute inflammation (appendicitis).

Although acute appendicitis is a very common disease and, with 7 to 12 percent of cases, is the most common emergency in abdominal surgery, early diagnosis is difficult due to the different positional anomalies and the very different pain localization. In addition, the classic symptoms such as loss of appetite, pulling and colic-like pain in the umbilical area or epigastrium (upper abdominal area) with later relocation of the pain to the lower abdomen, nausea and vomiting as well as moderate fever manifest themselves in only about 50 percent of those affected.

The main complication of appendicitis is perforation. With an open perforation, the purulent secretion flows from the appendix into the free abdominal cavity and can cause life-threatening diffuse peritonitis (generalized inflammation of the peritoneum) with an increased risk of sepsis. The most common pathogens released include enterococci and Escherichia coli, in rarer cases salmonella, staphyloococci or streptococci.

A covered perforation leads to an abscess covered by the large mesh (perityphlitic abscess) with locally limited accumulations of pus in the right lower abdomen (local peritonitis). Even with appendicitis with perforation and peritonitis, the mortality rate is only 1 percent. In rare cases, malignant tumors can develop in the appendix (appendix malignancies).

.jpg)

.jpg)