The Eye muscles serve the motor skills of the eyeballs, the accommodation of the lenses and the adaptation of the pupils. The 6 outer eye muscles are able to move the two eyeballs in the same direction and synchronously or to focus on a target. The inner eye muscles focus on near or far vision and adapt the pupils to the strength of the incident light (comparable to the selection of the aperture on a camera).

What are eye muscles?

The outer eye muscles ensure the necessary eye movement in the three possible directions of rotation: nodding movement (up and down), turning sideways (right and left) and tilting (torsion).

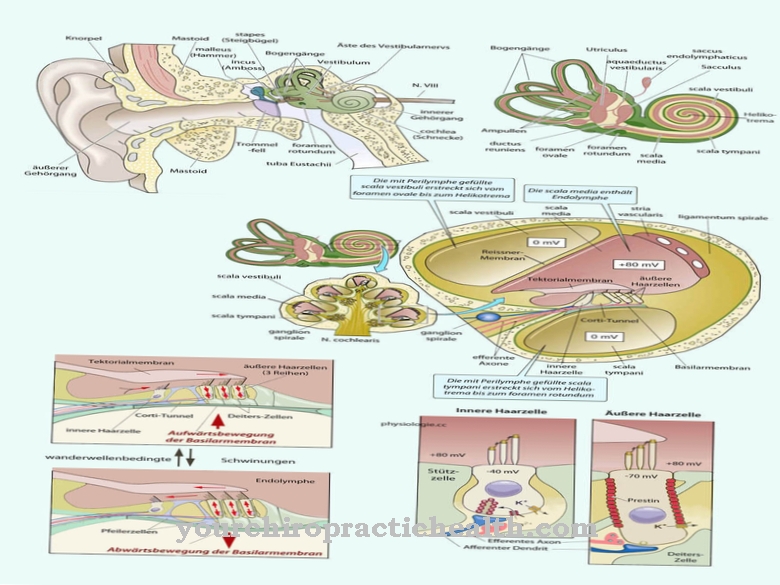

While the two directions of rotation, pitching and turning sideways, can be controlled at will, the torsion is physically severely restricted. It is activated almost exclusively by involuntary stimuli from the vestibular system (organ of equilibrium).

The eyeballs are usually rotated in the same direction and synchronously. However, to a limited extent, deliberately controlled movements in opposite directions are also possible, for example internal squinting. Since the outer muscles of the eye are skeletal muscles, the eyes can be moved at will.

But there is also an involuntary eye movement in all directions, which works almost without distortion and is controlled by the vestibular system in the middle ear so that the last image is not lost from the eye when the head is moved quickly or when accelerating. This is comparable to the recordings of a gyro-stabilized camera.

The inner (smooth) eye muscles, which are subject to the autonomic nervous system, accommodate the lens of the eye from near vision to far vision and vice versa. Two tiny inner eye muscles adapt the pupil to the corresponding light conditions.

Anatomy & structure

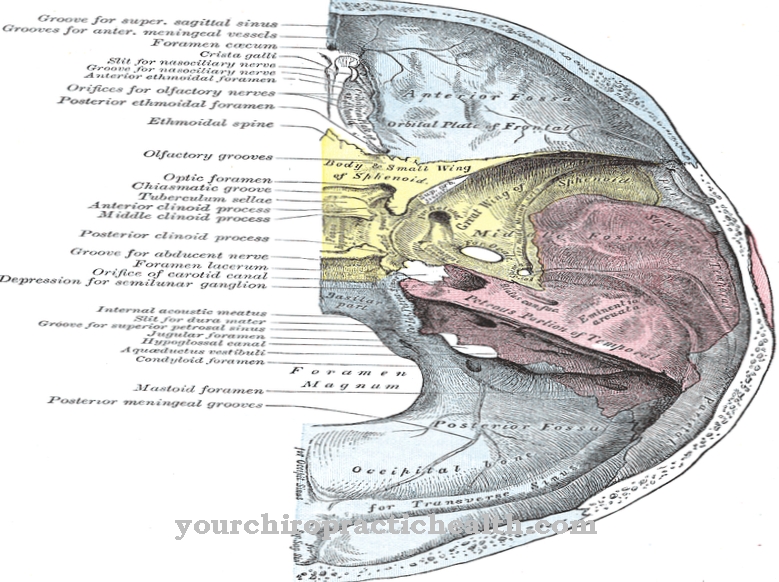

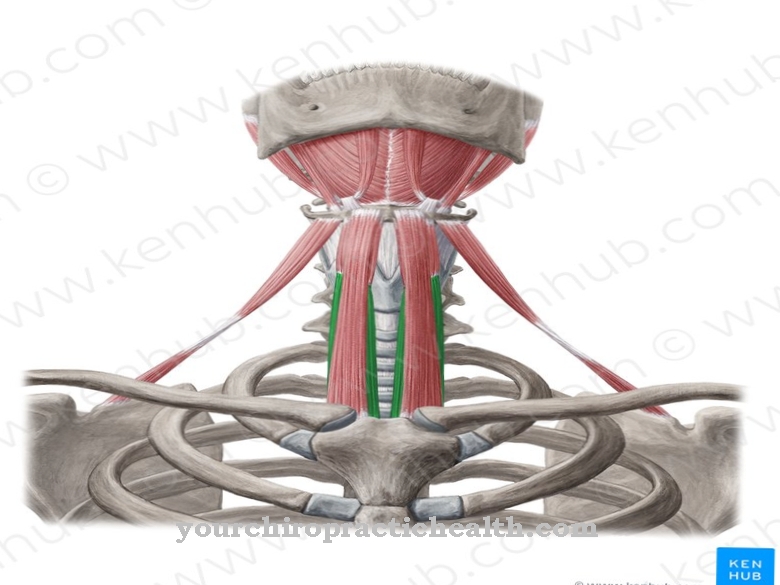

The outer eye muscles include 4 straight and 2 oblique eye muscles, which in pairs act as antagonists. Except for the upper oblique eye muscle, all external eye muscles arise at the tip of the bony eye socket. From there they run like a funnel to the eyeball (bulbus oculi), where they have attached to the dermis of the eyeball.

The eyelid lifter also originates in the same place and runs in the upper eye socket to the eyelid. The eyelid lifter is not only activated voluntarily, it is also connected to the upper straight muscle. This supports him as an agonist, which means that the eyelid automatically moves up when the eye rolls up and vice versa.

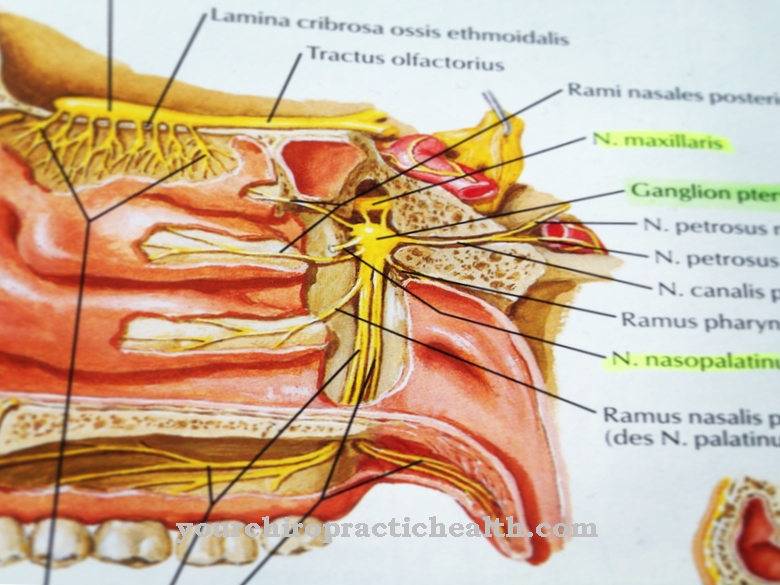

The outer eye muscles consist of striated skeletal muscles that are subject to the will and are innervated by three cranial nerves. The inner eye muscles consist of the paired ciliary muscles, which flatten the lens when tensed and cause a longer focal length.

From the two antagonistic muscles that cause the pupil to adapt as a reaction to the incident light intensity. The inner eye muscles are stimulated parasympathetically and can therefore not be controlled voluntarily.

Tasks & function

The main purpose of the outer eye muscles is to turn the eyes synchronously and parallel in the two directions up-down and right-left. In order to enable spatial vision, the outer eye muscles align the eyes so that the object we want to look at is in the Fovea centralis of both eyes, the point of sharpest vision on the retina.This means that the central lines of sight of both eyes always intersect at the level of the object. At close distances this can be equated with squinting, while the viewing axes of the eyes are practically parallel to objects at great distances. If we turn our eyes willingly or involuntarily in any direction, the muscles report the movement to the visual center in the brain, so that the brain interprets the image shift on the retina as a proper movement of the eyes and not as a movement of the object or the entire environment.

Another task is to perform a so-called microsaccade one to three times per second. The eyes are jerked by less than 30 arc minutes, which happens autonomously and completely unnoticed. The microsaccades cause the image on the retina to shift by around 40 photoreceptors. This prevents the photoreceptors (cones and rods) from being damaged by prolonged uniform exposure. The inner eye muscles have the task of autonomously accommodating the lens at changing distances and independently controlling the incidence of light by adapting the pupil.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines for eye infectionsDiseases

Functional disorders of one or more nerves that supply the external or internal muscles of the eye with motor are known as ophthalmoplegia. This then leads to symptoms of paralysis (paresis) in the affected eye muscles. A distinction is made between an internal and an external ophthalmic oplegia. If the outer and inner eye muscles are equally affected, it is a total ophtalmoplegia.

If only the outer eye muscles are affected, the exact automatic alignment of the eyes is disturbed, which can manifest itself in squint positions and the generation of double vision or similar symptoms. If the inner eye muscles are affected, this can be expressed, for example, by a wide, rigid pupil and / or by the inability to adjust the eyes to a certain distance, i.e. sharpness is lost.

The nerve damage can be caused, for example, by neurotoxins, by tumors or by aneurysms. If certain areas in the visual center of the brain are disturbed, there will be disturbances in the alignment of the eyes to gaze targets or eye tremors (nystagmus), which can be normal for a few seconds when stopping persistent body rotations (pirouette).

If the transmission of stimuli from the nerves to the eye muscles is disturbed, there may be myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disease that manifests itself in symptoms of muscle weakness in the eye muscles. Another autoimmune disease is Graves' disease, a disease that is usually associated with a thyroid malfunction. Symptomatic of the disease is protruding eyes, which is caused by changes in the tissue behind the eyeball.

.jpg)