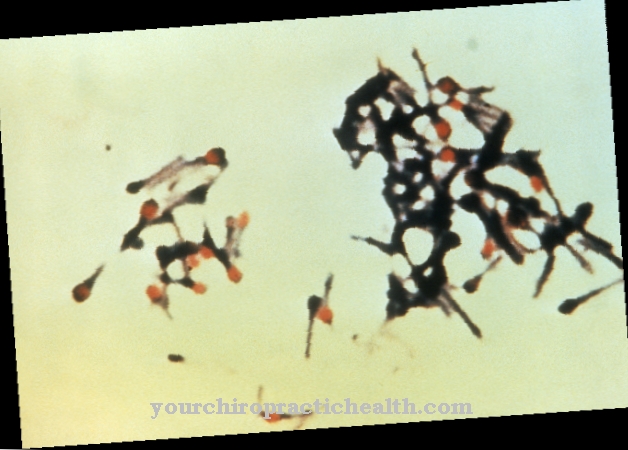

Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, obligate anaerobic bacterium from the Firmicutes division. The endospore former is one of the most important nosocomial germs and can lead to the occurrence of antibiotic-associated colitis, especially in the clinical setting.

What is Clostridium Difficile?

Clostridium difficile is a rod-shaped, gram-positive bacterium and belongs to the Clostridiaceae family. C. difficile is a facultative pathogenic agent that can lead to a life-threatening inflammation of the colon (pseudomembranous colitis), especially after taking antibiotics. This makes it one of the most relevant nosocomial pathogens ("hospital germs"), since broad spectrum antibiotics are often used in hospitals and the therapy times with antibiotic drugs are usually longer.

C. difficile is one of the obligate anaerobic bacteria and therefore has no way of active metabolism in an oxygen-containing (oxic) environment. Even small amounts of oxygen can be toxic to the bacterium.

In addition, this type of clostridia has the ability to form endospores that are very resistant to various environmental influences. If the cell perceives severe stress, the strictly regulated process of spore formation is initiated (sporulation). During sporulation, the vegetative cell forms an additional cell compartment which, among other things, protects the DNA and important proteins in the mature spore with a very stable cell envelope. The spore is released after the mother cell dies and thus ensures the cell's survival.

This metabolically inactive form of persistence means that stress factors such as heat, oxygen, drought or even many alcohol-based disinfectants can be tolerated until the spore can return to the vegetative state under more favorable environmental conditions.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

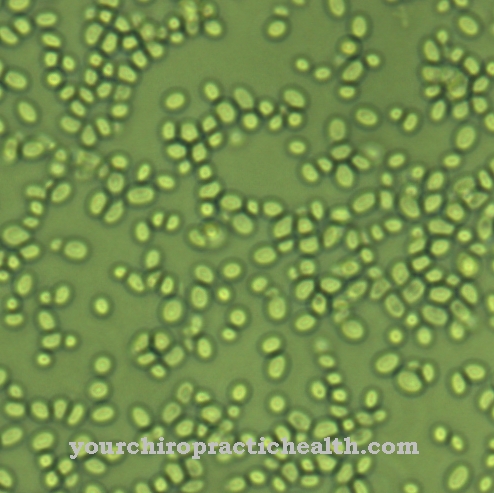

Clostridium difficile is basically widespread all over the world (ubiquitous) and occurs in the environment primarily in soil, dust or surface water. C. difficile can also be found in the intestines of humans and animals. A little under 5% of all adults carry the bacterium mostly unnoticed. In contrast, the germ was found in around 80% of all infants, making it probably one of the first bacteria to colonize the intestines of a newborn.

The high prevalence in hospitals is a serious problem. The bacterium can be detected in 20% - 40% of all patients and many patients also experience a new colonization with C. difficile, but without developing symptoms immediately. The frequency and severity of C. difficile infections are reported to have increased over the past few years. The very resistant spores, which are even resistant to many common alcohol-based disinfectants, have a high persistence in dirt, dust, on clothing or floors. This, together with the sometimes inadequate hygiene in hospitals, contributes to its rapid spread among patients.

This high rate of spread becomes problematic when one considers the conditions for an acute infection with C. difficile. In healthy people, a natural colonization of the (large) intestine with non-pathogenic bacteria (intestinal microbiota) represents protection against other, harmful types of bacteria. By adapting to and interacting with the human host, this microbiota can limit the growth of undesirable germs to a certain extent. Our normal intestinal microbiota includes bacteria of the genera Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium or Escherichia, as well as Clostridium species, but not Clostridium difficile.

If this microbiota is partially or completely killed by the ingestion of antibiotics, the spores of C. difficile can germinate in the anoxic environment of the large intestine and multiply strongly.

Even if the multiplication after taking antibiotics is the most common cause of an acute infection, older or immunocompromised patients are also at risk. In addition, in patients who take proton pump inhibitors to regulate gastric acid, there is a risk that the bacterium will not be killed by the gastric acid and will enter the intestine.

Typically, C. difficile infection results in severe diarrhea and inflammation of the colon. If the bacterium gets back into an oxygen-containing environment via the stool, sporulation starts immediately due to the oxygen stress. After excretion and sporulation, the spores can thus easily be transferred by the patient to other patients, staff or various surfaces. In this acute phase of the disease there is the greatest risk of infection and spread.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medication for diarrheaIllnesses & ailments

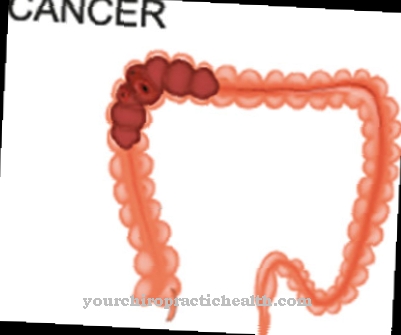

Clostridium difficile can cause a specific form of intestinal inflammation under certain circumstances described above (pseudomembranous or antibiotic-associated colitis). Typical symptoms include sudden onset of diarrhea, fever, lower abdominal pain, and dehydration and electrolyte deficiency associated with the diarrhea. Slightly pulpy diarrhea occurs in mild forms; in more severe cases, life-threatening inflammation and swelling of the entire large intestine (toxic megacolon), intestinal perforations or blood poisoning (sepsis) can occur.

It is important for the doctor to differentiate Clostridium difficile from other potential pathogens. Risk factors such as age, immunosuppression, the use of antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors or anti-inflammatory drugs serve as important indicators. Together with microbiological examinations and the detection of specific toxins produced by C. difficile, they can confirm a diagnosis.

The toxins are two of the major C. difficile virulence factors: TcdA (toxin A) and TcdB (toxin B). These are largely responsible for the damage to the intestinal tissue, whereby there are strains that do not produce toxin A and yet can lead to severe disease processes. In addition, studies have shown that toxin B is the more relevant factor and its effect is supported by toxin A.

Both toxins can penetrate the epithelial cells of the intestine, where they change both important structural proteins (actins) and signaling pathways within the cell (various GTPases that are involved in the organization of the actin skeleton). As a result, the cells lose their original shape (change in cell morphology) and important intercellular connections (tight junctions) can be destroyed. This leads to the death of the cells (apoptosis), the leakage of fluid and enables toxins or pathogens to penetrate deeper tissue layers and further damage the mucous membrane. The damaged cells together with cells of the immune system and fibrins form the typical pseudomembrane, which in endoscopic diagnostics can be regarded as a sufficiently clear identification of a C. difficile infection.

.jpg)