The Cervical fascia consists of three distinct layers and a further fascia that envelops the most important parallel cervical arteries, the most important head and neck vein and the vagus nerve. The neck fascia, composed of collagen and elastin, are closely connected to the rest of the fascia system of the body and are largely responsible for the shaping of the enveloped organs and muscles in the neck area.

What is the neck fascia?

Neck fascia summarizes several fasciae that can be anatomically assigned to the neck area. The largest part of the neck fascia consists of three distinct layers, which are called sheets or laminae.

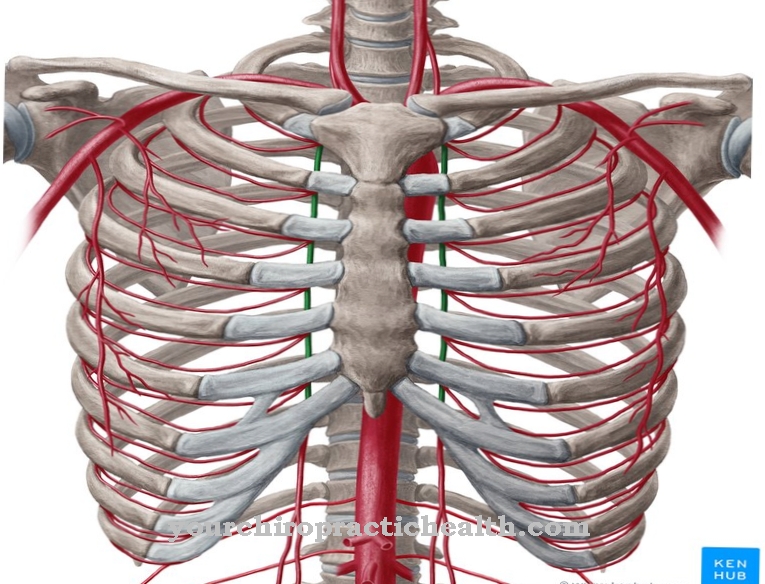

Other fasciae such as the carotid vagina, which mainly envelops the two cervical arteries, the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein and part of the vagus nerve, are also included in the cervical fascia. As part of the collagenous and elastic connective tissue, the neck fascia has the task of holding the vessels, muscles and the trachea, esophagus and thyroid in place and giving them their external shape. In addition, the fasciae enable the organs and muscles to move almost without friction.

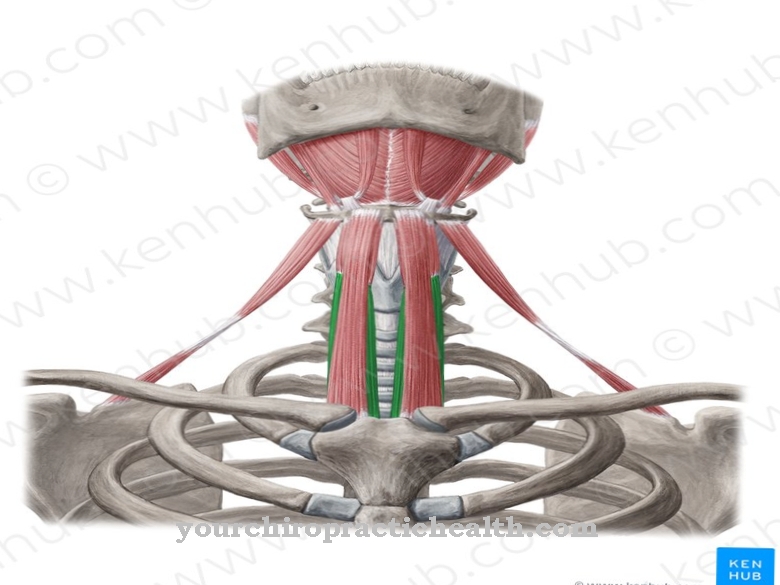

In order to fulfill its tasks, the neck fascia is divided into three so-called sheets or laminae, which lie on top of each other. These are the superficial lamina, which spans the entire neck below the skin, the praetracheal lamina and the prevertebral lamina. The cervical fascia also includes the carotid vagina, which surrounds the so-called vascular nerve cord of the neck.

Anatomy & structure

The neck fascia are made up of skins that are mainly composed of collagen and elastin. The firmness and elasticity of the fascia depend on the anatomical needs. Muscles, vessels, organs or nerves are enveloped by fasciae that are connected to each other, so that fasciae determine the three-dimensional space of the body and regulate body tension via the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves.

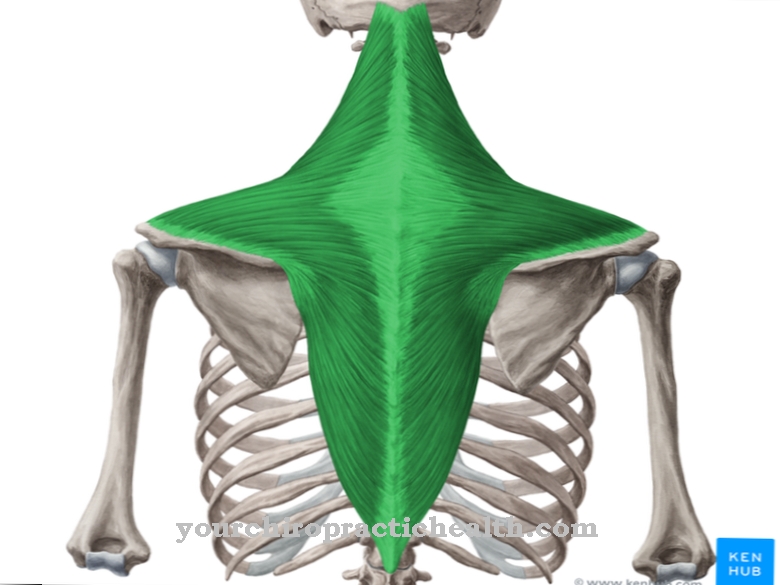

The superficial fascia, which spans the entire neck below the fatty tissue of the skin, splits in each case on the large surface muscles, the head turner and the trapezium, so that the two muscles are literally embedded in the divided superficial lamina. As the process continues, the split parts reconnect. All neck fasciae are closely connected to one another like a network, so that the tension or relaxation of only one fascia affects the other fasciae. Tension and relaxation are controlled by the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems are part of the autonomic nervous system and innervate the fasciae.

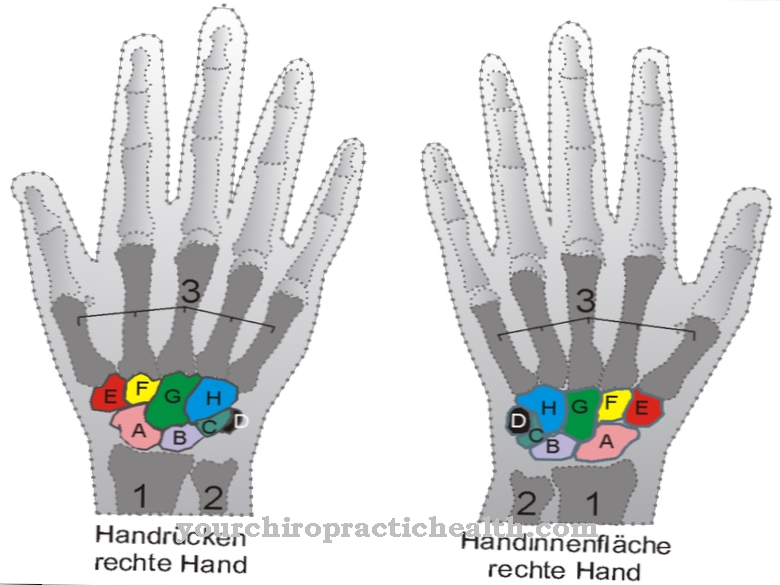

The neck fascia also contain a multitude of sensory nerve endings for pain perception (nociceptors), mechanoreceptors, thermoreceptors and chemoceptors, which allow the brain to “assess the position”. To control the fascia tension, the fasciae are also connected to efferent motor nerves that can exert contractile stimuli on the myofibroblasts. These are connective tissue cells that have similar properties to cells of the smooth muscles and are part of the fascia in different concentrations. The fasciae are supplied and disposed of via a network of arterial, capillary and venous vessels as well as numerous lymphatic vessels that are connected to the fasciae.

Function & tasks

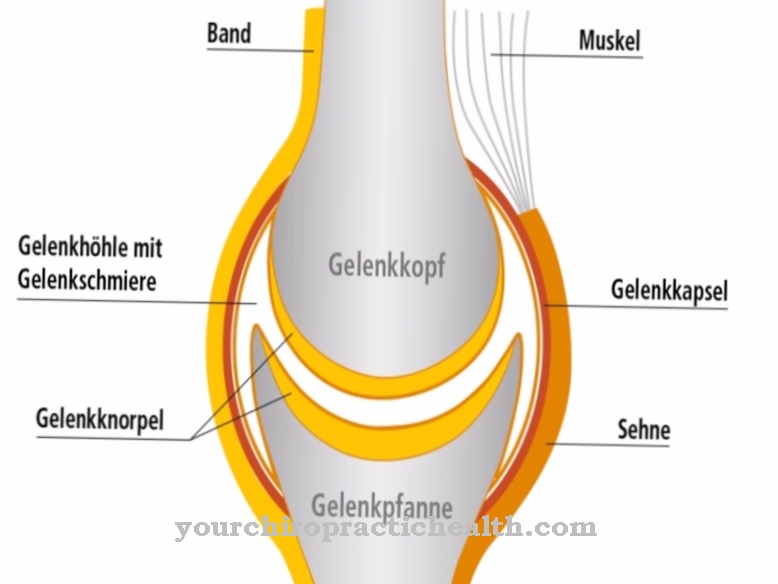

One of the main tasks of the neck fascia is to hold vessels, nerves, muscles and organs that run or are located in the neck area in place and to ensure that they can be moved as smoothly as possible within certain limits that guarantee freedom of movement for the neck . The freedom of movement of the joints is largely dependent on the elasticity of the fascia. The elasticity and tensile strength of the fasciae are tailored to their tasks, so that the outer, middle and inner fasciae differ in their properties.

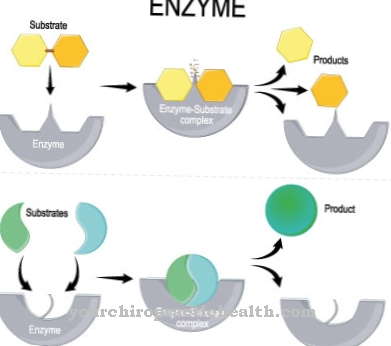

The variable tension of the cervical fascia not only holds the individual, delimitable systems in their position, but also supports the muscles in their function. For example, an elastically pre-stretched fascia functions as a mechanical energy store. During the contraction of the muscle, the tensile tension in the fascia is released and the released mechanical energy supports the muscle contraction. Via their numerous receptors for pain, temperature and mechanical and chemical stimuli such as pH value and oxygen partial pressure, they report "status reports" to the responsible brain centers, which then create a "situation assessment" and react with locally or systemically effective stimuli.

The fasciae also serve as a mechanical and chemical barrier to protect the enveloped organs against pathogens, and through their water storage capacity they play a large part in regulating the water balance.

Diseases

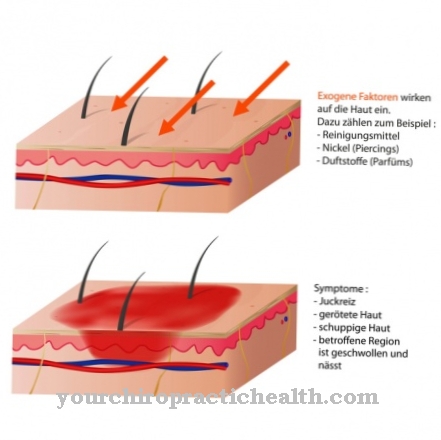

One of the most common problems related to the fascia arises from the control of tension via the sympathetic nervous system. Frequent stressors that cause the sympathetic nervous system to constantly release stress hormones can lead to a chronically increased concentration of stress hormones in the body.

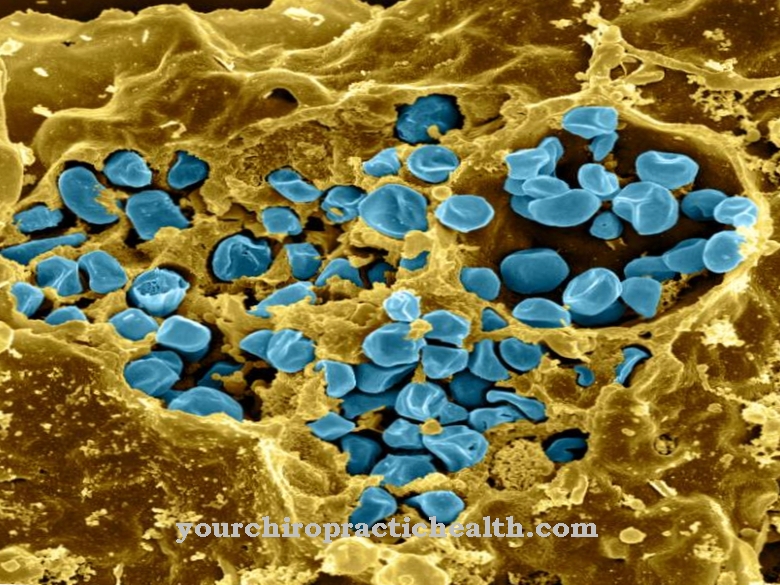

The fasciae react to this with a kind of constant tension, so that the normal alternation between tension and relaxation is greatly reduced. This leads to a reduction in the lymph flow between the fasciae, which means that the fibrinogen contained in the lymph, a coagulation factor, accumulates in the tissue and is converted into fibrin, the body's own "glue". The fibrinogen glues the fascia together and can lead to considerable discomfort.

Adhesive neck fasciae can result in a significant restriction of movement of the neck, but also lead to considerable pain if the nerves running between the fasciae are squeezed and cause unspecific pain or sensory problems. The symptoms are known under the term myofascial syndrome (MFS). Because of the network-like connection of all fasciae with one another, the pain caused cannot always be localized.

.jpg)