Of the Ileum is the last section of the small intestine, which is separated from the large intestine by the so-called ileocecal valve. On the other hand, however, it emerges from the jejunum without a sharp border.

What is the ileum?

The ileum, too Ileum called, represents the third and last part of the small intestine. It follows the empty intestine (jejunum) without any recognizable border and ends in front of the so-called Bauhin's valve (ileocecal valve), which separates the small and large intestines. The ileum, together with the jejunum and duodenum, perform the functions of the small intestine.

The ileum and the empty intestine in particular form a functional unit. Their fine-tissue structure changes only gradually from the end of the duodenum to the ileocecal valve. A clear boundary between the two sections of the small intestine cannot therefore be seen.

Within this range the nutrients from the chyme are absorbed. Adapted to the change in the composition of the chyme during the passage through the small intestine, however, the size, shape and number of the intestinal villi and other fine-tissue structures, especially within the ileum, change.

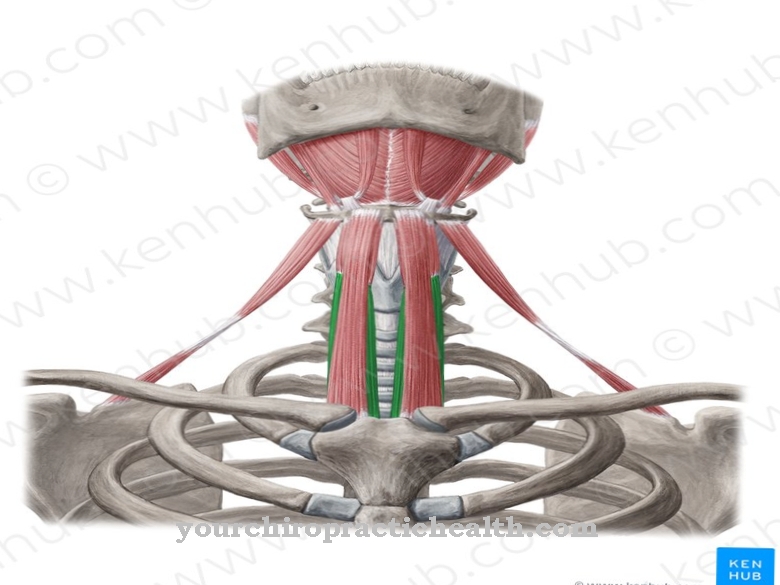

Anatomy & structure

The ileum and jejunum are attached to the abdomen via the mesenteries. There it is supplied with blood via the arteriae ileales, which arise from the arteria mesenterica superior.

In humans, the ileum is about three meters long, making up 60 percent of the length of the small intestine. The differences between the ileum and the anterior jejunum are inconspicuous. The ileum is a little paler and has a slightly smaller diameter. The mesentery of the ileum, however, is somewhat richer in fat.

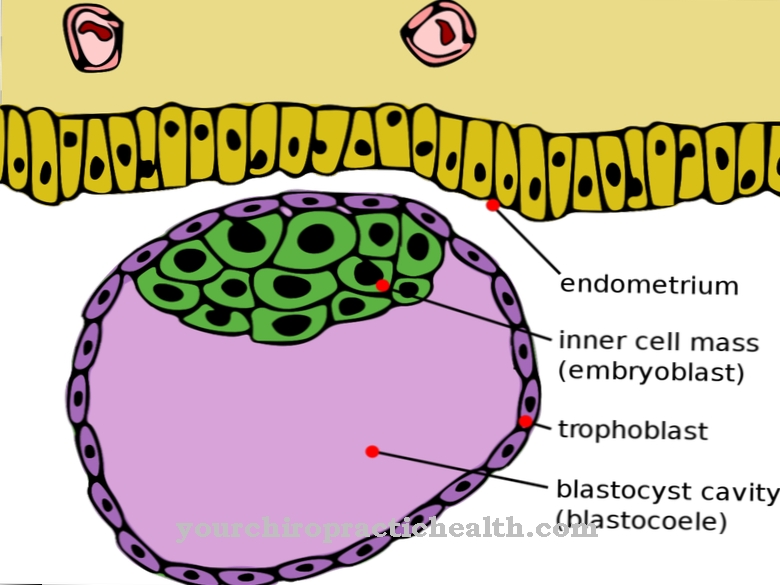

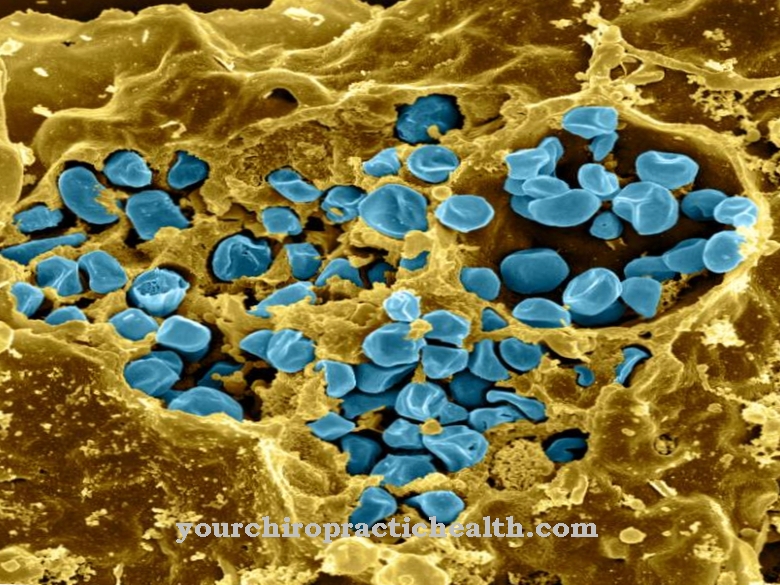

Most striking, however, is the fact that the ileum, in contrast to the jejunum terminal, contains a large number of Peyer's plaques. Peyer's plaques are closely spaced lymph follicles. Their job is to fight off the germs ingested with food. Furthermore, the ileum only contains very few kerkring folds, which are responsible for intestinal peristalsis.

Towards the end, the intestinal villi also disappear because the chyme no longer contains any absorbable nutrients before it enters the large intestine. On the anal side, the ileum closes with the so-called Bauhin's valve (ileocecal valve). The ileo-caecal valve is a functional sphincter that arises from the circular muscle layers of the ileum and the appendix upstream of the colon (ceacum). It is designed to prevent the bacteria-rich, indigestible food residues from flowing back from the large intestine into the sterile ileum.

Function & tasks

Like the previous jejunum, the ileum has the task of continuing to absorb nutrients from the chyme. This requires a large surface area of the intestinal mucosa, which is ensured by the intestinal villi and microvilli. However, the villi become smaller and smaller towards the large intestine and at the end they disappear completely because there are no more absorbable nutrients in the chyme in the terminal area of the ileum.

In addition to the unchanged absorption of water, vitamin B12 (cobalamin) and bile acids are absorbed by the intestinal mucosa. Vitamin B12 is responsible for blood formation, cell division and the functioning of the nervous system. This underlines the special importance of the ileum, because a disorder of the absorption of vitamin B12 leads to pernicious anemia (malignant anemia).

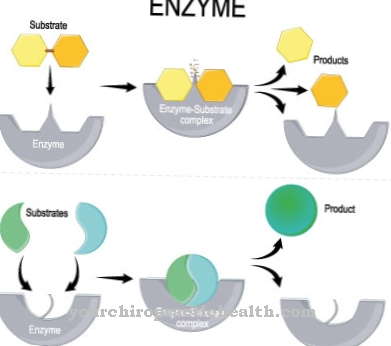

The absorption of vitamin B12 takes place with the help of the intrinsic factor. The intrinsic factor is a glyco-protein that binds cobalamin to protect against the digestive enzymes pepsin and trypsin, which are produced in the stomach. This protein is in turn produced by the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa. Furthermore, the small intestine absorbs a total of 80 percent of the water from the chyme.

However, this applies equally to all sections of the small intestine. Last but not least, defensive reactions against the bacteria ingested with food take place in the ileum with the help of lymph follicles (Peyer's plaques).

Diseases

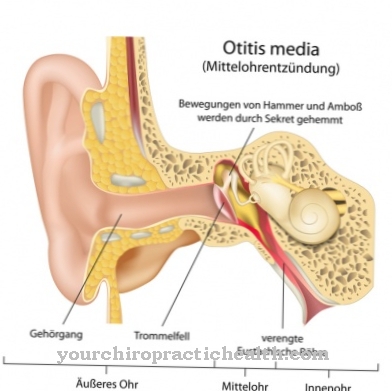

Diseases of the ileum usually do not occur in isolation. Usually other areas of the intestine are also affected. The intestinal inflammation can be both infectious and non-infectious in nature. A satisfactory diagnosis can rarely be made based on symptoms alone.

Both small intestine and colon inflammation cause similar symptoms. Inflammation of the small intestine is known as enteritis. For example, if the stomach is involved, it is gastroenteritis. If the large intestine is affected in addition to the small intestine, enterocolitis is present.

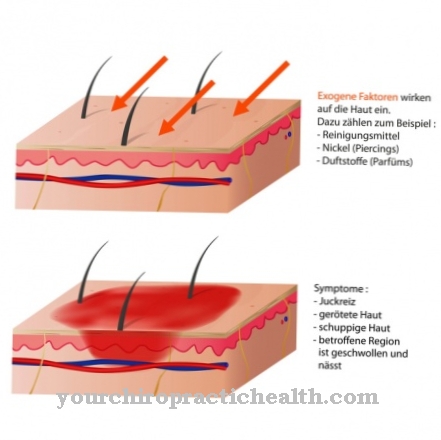

Infectious bacteria that can cause enteritis include salmonella, shigella, clostridia or Escherichia coli. Viruses such as rotaviruses, adenoviruses or noroviruses also often lead to severe inflammation of the small intestine.Non-infectious enterites are caused, for example, by drugs, food intolerance, allergies or autoimmune processes.

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are autoimmune diseases. While Crohn's disease affects the entire intestine, ulcerative colitis is often limited to the colon only. But ulcerative colitis can also spread to the small intestine. Inflammatory processes in the large intestine often also affect the Bauhin's valve between the ileum and large intestine. If the ileocecal valve is inflamed, it can no longer close properly. The result is a migration of bacteria from the large intestine into the sterile ileum.

Since the ileum is also responsible for the absorption of vitamin B12, inflammatory processes in this area can also impair its absorption. In addition to the lack of the intrinsic factor due to gastric diseases, this is one of the most common causes of pernicious anemia. Cancers of the ileum are rare because the rapid passage of the chyme prevents the accumulation of carcinogenic substances in this area.

Typical & common bowel diseases

- Crohn's disease (chronic bowel inflammation)

- Inflammation of the intestine (enteritis)

- Intestinal polyps

- Intestinal colic

- Diverticulum in the intestine (diverticulosis)

.jpg)