The genus Pestivirus includes several viruses in the Flaviviridae family. These viruses specialize in mammals. Pestiviruses particularly affect cattle and pigs and cause serious diseases in them, some of which lead to considerable economic damage.

What are pestiviruses?

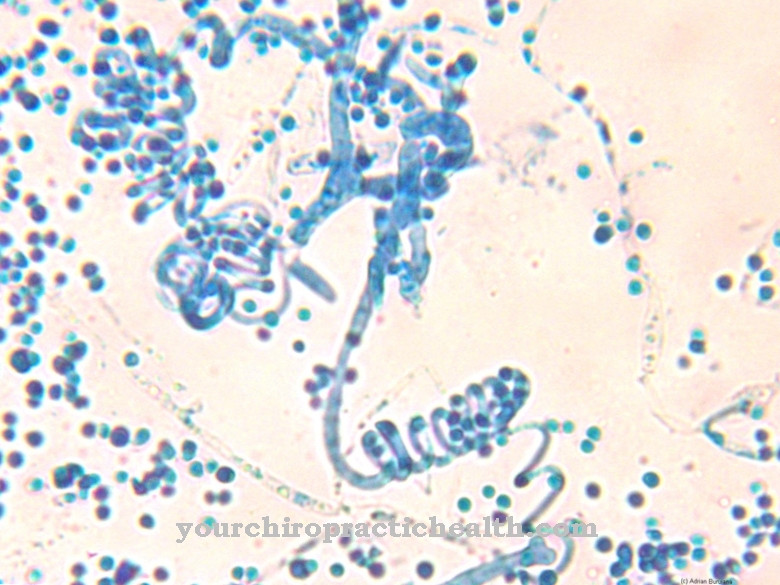

Viruses of the genus Pestivirus, like all Flaviviridae, are single-stranded RNA viruses. Your virus envelope consists of the lipids of your host cell. The genetic material of the virus is stored in it. The viruses also replicate within the original host cell. For this purpose, the pestiviruses first attach to cells of the host organism and penetrate the cell envelope. After the positive-stranded viral RNA strand has been duplicated, the new virus buds.

Viruses of the genus Pestivirus are usually irregularly spherical and about 40 to 60 nm in diameter.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

Viruses of the genus Pestivirus are common in various mammalian species. They are particularly common in pigs and cattle. It is usually transmitted through direct contact with sick animals, which is why pestiviruses can occur more frequently, especially in factory farming and large herds. Infections can also break out in smaller farms, however, since no symptoms are usually noticeable during the incubation period and some of these viruses also have a constant reservoir of pathogens in wild forms of today's farm animals. In addition, pestiviruses can remain infectious outside the host body for several weeks.

While the swine fever pathogen, which belongs to the genus pestivirus, occurs particularly frequently in Europe, viruses that attack cattle are more widespread in other parts of the world. These pathogens are particularly problematic in Australia, where the widespread spread of pestiviruses repeatedly causes major economic damage. Restricted to Africa, it is a pathogen belonging to the genus Pestivirus that primarily attacks giraffes.

Animals infected with pestiviruses should under no circumstances be consumed by humans. Not all animal pathogens can survive in the human organism, but some can. If people then eat this meat, they can also become ill.

Illnesses & ailments

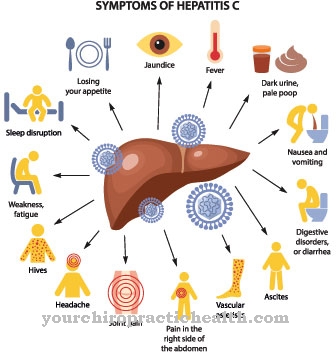

The penetration of viruses of the genus Pestivirus into the cells of the host organism does not necessarily destroy them. Depending on whether this is the case, the symptoms differ in type and severity. While an infection can go almost unnoticed in some animals, so that they become permanent excretors, others experience fever, diarrhea, bleeding, changes in the mucous membranes and disorders of the central nervous system. In severe cases, this can be fatal. Death mostly occurs from circulatory failure. Secondary infections can also lead to the death of the animal.

An infection with a virus of the genus Pestivirus is particularly problematic if you are pregnant at this time. In this case, miscarriages or stillbirths can occur. In live births, deformities of the young animals and premature death are possible. In addition, infection with pestiviruses can cause permanent sterility in the affected animals. Visible symptoms in this case are only mild symptoms such as low fever and reddening of the mucous membranes.

The animals seem to recover after a short time, although the disease has actually become chronic. In addition to the direct damage caused by infertility, these animals also represent a permanent threat to the rest of the population due to the continued excretion of pathogens. In the case of older and robust animals, however, complete recovery can occasionally occur.

The viruses of the genus Pestivirus include in particular the pathogen causing swine fever and the bovine virus diarrhea virus. Border disease, which can occur in sheep and is named after the English-Scottish border area where it first appeared, is also one of the diseases caused by viruses of the genus Pestivirus.

Depending on the species and virus, different symptoms and consequences come to the fore. While swine fever is usually fatal, problems with pregnancy and fertility are the main problems in cattle and especially sheep. Vaccinations are now available for some of these animal diseases. However, these are not approved in all countries, as blood tests cannot differentiate between vaccinated and infected animals. As a rule, prophylaxis in farm animals is therefore only carried out through strict control of the animal population, separation of newcomers and the weeding out of sick animals. In stables, the use of disinfectants can prevent the spread of viruses of the genus Pestivirus, as this puts them in an inactive state.

In the case of an infection with pestiviruses, no therapy for the actual disease is known; only secondary infections can be treated. In order not to endanger the still healthy animal population, at least all sick animals are culled, and in the case of swine fever, all healthy animals within a certain radius around the epidemic.

In order to prevent the unhindered spread of diseases caused by viruses of the genus Pestivirus and to be able to take successful control measures in good time, an outbreak of one of these diseases must be reported in many countries. The responsible authorities then decide on the necessary measures, organize the culling of the affected stocks if necessary and carry out thorough investigations before animals can be kept again at the respective location. The economic damage is therefore usually very great if infections with pestiviruses occur.

.jpg)

.jpg)