As Racemate is a mixture of two chemical substances that only differ in their three-dimensional structure. These relate to one another like image and mirror image and can each have very different pharmacological effects on the human body.

What is a racemate?

A racemate (also a racemic mixture) describes a mixture of two chemical substances that are present in the same proportion to one another. They differ in their three-dimensional structure, which results from the respective arrangement of the atoms.

If an atom has four bonds to four other different atoms or groups of atoms, this atom is called chiral. If a chemical compound has at least one chiral atom, the four binding partners can adopt two different arrangements around the chiral atom.

This results in two substances, so-called enantiomers, which in their spatial structure behave like a picture and a mirror image or like a left and right glove: Although they contain exactly the same atoms or groups of atoms, they cannot be brought into congruence and are therefore separate from each other clearly distinguishable. They are usually referred to as (R) and (S) enantiomers.

Pharmacological effect

The enantiomers of a substance differ in their physical properties only in terms of their optical activity. A substance is optically active when it measurably changes a certain property of the light when it passes through it. This is one of the ways to differentiate the respective enantiomers and is an essential criterion when testing the purity of a potentially racemic mixture.

Enantiomers often differ considerably in their physiological properties, which means that their differentiation or the purity of a racemate is of great importance in pharmacy. Every drug has a place of action in the human body, a so-called target, at which it is recognized by the body's own structures. These structures are mostly themselves chiral and usually only recognize a certain enantiomer of a substance.

Therefore, in the manufacture of drugs, it is extremely important that only the effective enantiomer is included in the product. Otherwise, serious side effects can occur, as the (often less effective) mirror-forming enantiomer, for example, binds to a completely different place in the body and can trigger an unwanted reaction.

It is also possible that the wrong enantiomer could be broken down by an enzyme in the body before it even reaches its target. Or it binds to a transport protein and thus reaches an undesired location in the body. The possibilities for interaction are extremely diverse, which is why the side effects are hardly predictable if a racemate or non-enantiomerically pure mixture is present in the product.

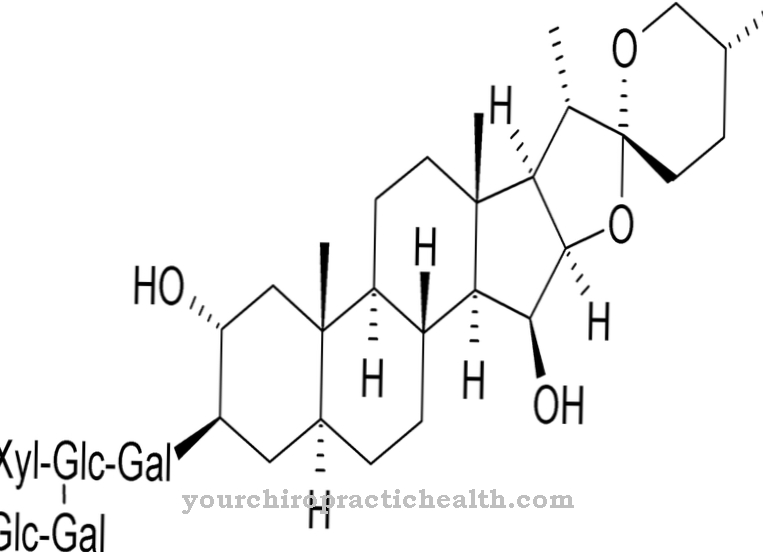

A less serious but practical example are flavorings. The olfactory receptors in our nose also have a chirality and are tailored to recognize certain substances. One enantiomer of the natural product carvone smells of caraway, the corresponding mirror-forming enantiomer, however, of mint.

Medical application & use

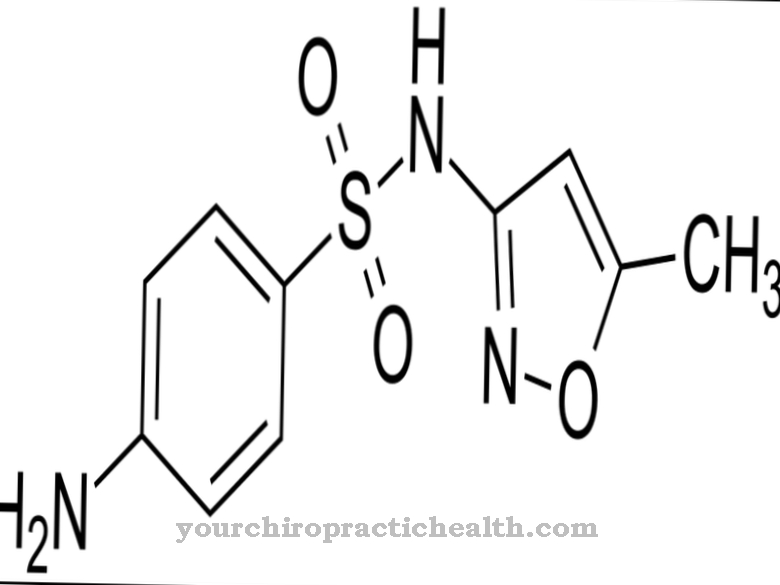

Many of the organic compounds that are used as active ingredients in drugs have chiral atoms and thus different enantiomers. Therefore, during the synthesis of these substances, care must be taken to obtain a product that is as enantiomerically pure as possible.

The subsequent separation is technically very complex, which is why side effects are tolerated in some cases and a racemate is approved as a drug. Since the associated enantiomers often have different potency, the final medicinal product must be dosed higher in this case in order to achieve the same effectiveness as that of an enantiomerically pure drug.

For example, the anesthetic ketamine has an (S) -enantiomer, which has a better analgesic and anesthetic effect and fewer psychotropic side effects than the corresponding (R) -enantiomer. Here it is advantageous for the patient if the (S) -enantiomerically pure medicinal substance is used.

Another example is the pain reliever ibuprofen, which is usually available as a racemate. Only the (S) -enantiomer has an analgesic effect, the (R) -enantiomer, however, is as good as ineffective. However, a certain proportion of the latter is converted into the effective (S) form in the body by an endogenous enzyme. There is therefore no need for a complex synthesis or subsequent separation of the enantiomers.

Risks & side effects

The ineffectiveness of an enantiomer is a comparatively harmless side effect of using a racemic mixture as a drug. A tragic example of very serious side effects is the sleeping pill Contergan with the active ingredient thalidomide. Contergan was advertised as a non-lethal sleep aid in the 1950s and was popular with pregnant women because it also reduced morning sickness. The animal experiments carried out up to then showed hardly any side effects. After the market launch, however, more malformations occurred in newborns and the drug was withdrawn from the German market after four years.

Many studies then examined the mode of action of thalidomide and were able to show that the molecule binds to a growth factor in the unborn child and thus interferes with embryonic development. So far, this teratogenic effect could not definitely be ascribed to either of the two enantiomers, especially since the two enantiomers convert into one another in the body. However, similar studies suggest that the (S) -enantiomer of thalidomide may have more damaging effects.

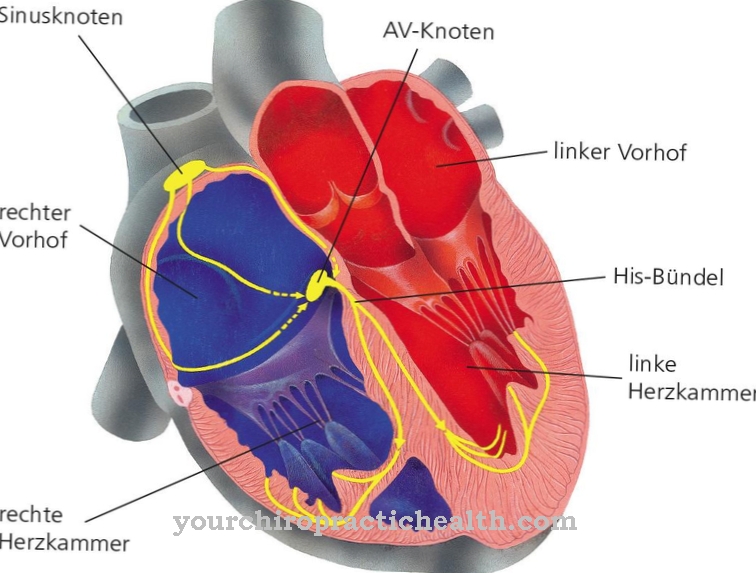

With the local anesthetic bupivacaine, there is a significant risk of accidental entry into the bloodstream. The (R) -enantiomer triggers a stronger drop in heart rate than the corresponding (S) -enantiomer. However, both show a comparable anesthetic effect. If an (S) -enantiomerically pure active ingredient is used here, these serious side effects for the patient can be reduced.