Four different families of gram-negative, extremely thin and long, helical bacteria that can actively move make up the group of Spirochetes. They occur in soils and bodies of water and as parasites or commensals in the digestive tract of mammals, molluscs and insects. Different types appear to cause spirochetoses in humans, including diseases as diverse as borreliosis, leptospirosis and treponematosis.

What are spirochetes?

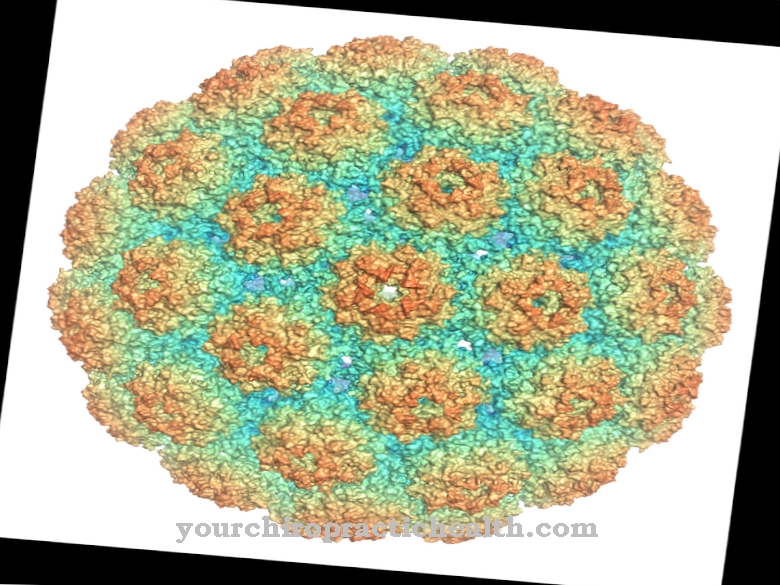

Spirochetes embody a group of gram-negative bacteria that are characterized by a very thin and corkscrew-like twisted (helical), flexible, long cell body. Their diameter reaches only 0.1 to 3.0 micrometers, while in some species their length can be up to 250 micrometers.

Spirilla, for example, a group of also helical bacteria, differ from spirochetes in their outer flagella and rigid cell body, while that of spirochetes is flexible and pliable. The small diameter allows them to easily pass through bacterial filters.

Spirochetes can actively move using a unique system of movement. It consists of bundled thread-like proteins (fibrils) and axially arranged filaments, which are also known as endoflagella or internal flagella, because they are located within the cell body. Endoflagella allow them to actively move in a winding or rotating motion. With the help of the fibrils and endoflagellates, the bacteria can also move jerkily. Some of the filaments consist of tubulin-like scaffold proteins, which are rarely found in bacteria.

The milieu in which spirochetes can thrive varies widely. Strictly anaerobic spirochetes can be distinguished from facultative anaerobic and aerobic spirochetes. There are also microaerophilic species that only find growth conditions when the oxygen concentration is far below normal atmospheric oxygen content.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

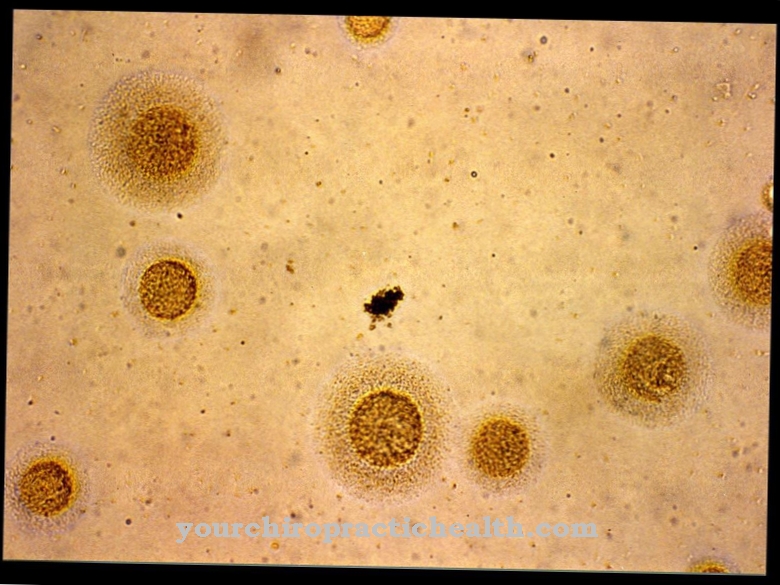

Spirochetes form a very heterogeneous group within bacteria. Some authors advocate assigning the spirochetes, of which only four different families are known, to a class of their own. In accordance with the very heterogeneous metabolism of the spirochetes, their distribution and occurrence is also true. Spirochetes are widespread as free-living bacteria in soil, water and water sludge. These are species that have no health relevance for humans.

Other types of spirochetes colonize the digestive tract of molluscs, insects, and other arthropods. The rectum sections of wood-eating insects such as termites are particularly covered with spirochetes. The bacteria in wood-eating insects may play a role in breaking down lignin.

Various types of spirochete can also be detected in the entire digestive tract of mammals and humans. Spirochetes even form part of the oral flora in mammals and humans. They are even found in the rumen of ruminants.

In the vast majority of cases, spirochetes occur as commensals or parasites. This means that they predominantly develop a neutral to slightly parasitic effect in the digestive tract. A possible, direct health benefit for humans has not yet been proven.

However, a few types of spirochetes from each of the four families are highly pathogenic. They cause mild to serious diseases that can be transmitted through insect bites, tick bites or through direct introduction of the pathogen through the smallest skin lesions or through contact with the mucous membranes. In most cases, the pathogens can be combated well with antibiotics during the early stages of the disease.

Illnesses & ailments

Lyme borreliosis, for example, is widely known and is almost exclusively transmitted by infected ticks. The disease is triggered by Borrelia burgdorferi type, which counts among the spirochetes, and takes very different courses that can lead to problems even after years. The lymphatic system and cranial nerves are often affected. For example, facial paralysis on one or both sides or myocarditis can occur as a result of the infection.

Other types of Borrelia are known to cause the disease. The venereal disease syphilis, also called hard chancre or French disease, is caused by Treponema bacteria, which also belong to the group of spirochetes. The disease is transmitted almost exclusively during sexual intercourse through contact with the foci of inflammation on the external genital organs.

Treponema pertenue, a treponema bacterium that also belongs to the spirochaetes, is the trigger for another treponematosis, the so-called yaws. The non-venereal infectious disease of the tropics shows up first as itchy and oozing, raspberry-like papules on the lower legs - in children often also on the face. If left untreated, the disease leads to serious changes in the bones and joints in the third stage, which sometimes only breaks out after a rest period of 5 to 10 years. The infection usually occurs through insect bites, but the bacteria can also penetrate the body through direct skin contact with the papules, via the smallest skin lesions. The disease can be treated well with antibiotics in the early stages.

One of the four families of the spirochetes is formed by leptospira, some of which are also pathogenic for humans. They are the cause of so-called leptospiroses. Of several known leptospiroses, only Weil's disease shows a severe course if left untreated. Leptospiroses are known by names such as rice fever, swinekeeper disease or sugar cane fever. The names suggest that close contact with animals poses a risk of infection. Infected mammals such as rats, mice, dogs and hedgehogs as well as pigs and cattle excrete leptobacteria into the environment through their urine, which enter the body through the smallest lesions of the skin or through the mucous membranes. Leptospiroses have become very rare in Germany thanks to the hygiene practices and the availability of effective antibiotics.

.jpg)