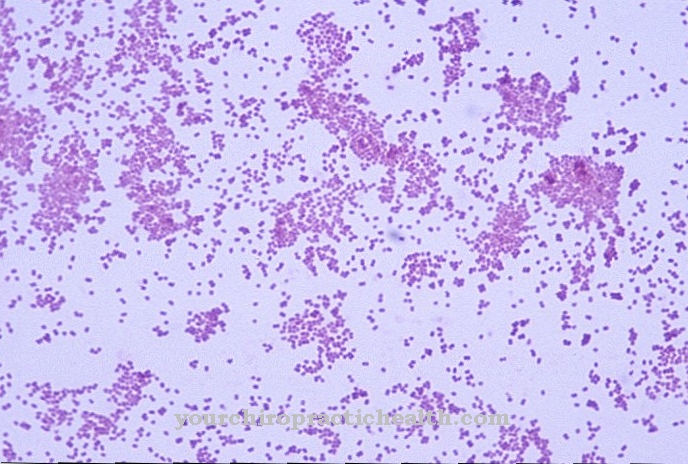

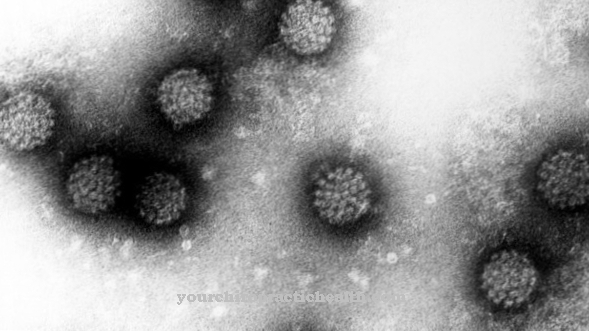

Trypanosomes are unicellular eukaryotic parasites that are equipped with a scourge and are also counted among the protozoa. The trypanosomes occurring worldwide have slender cell bodies and are classified by the exit point of their flagella. Characteristic of these pathogens for some tropical diseases such as sleeping sickness is the obligatory host change between an invertebrate vector and a vertebrate.

What are trypanosomes?

Trypanosomes are single-celled, flagellated parasites that are classified among the protozoa due to their cell nucleus and other organelles. Of the several hundred species of the genus Trypanosoma, only a few are pathogenic for humans and cause diseases such as sleeping sickness in West and East Africa and Chagas disease in Central and South America.

Trypanosomes have slim cell bodies and are characterized by the obligatory host switch between an invertebrate vector, also called a vector, and a vertebrate, which also includes reptiles, birds and fish. Since many species live very host-specifically, the corresponding type of trypanosomes can only occur in the distribution area of the intermediate host and the "final host".

Trypanosomes can be divided into the forms trypomastigote, epimastigote and amastigote with regard to the starting point of their flagella. In trypomastigotic trypanosomes, the flagellum arises at the rear end of the cell, in epimastigotic forms in the middle and in amastigotic forms, no external flagellum can be seen.

Another distinction can be made with regard to the route of infection. The trypanosomes that multiply in the end part of the insect's intestine and are excreted with the faeces are called sterocoraria and those that are transferred with the proboscis when sucking blood are called salivaria.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

Trypanosomes are widespread all over the world, but the species pathogenic to humans are largely restricted to tropical Africa and Central and South America. The pathogens for humans include Trypanosoma brucei (African sleeping sickness) and Trypanosoma cruzi (Central American Chagas disease). Sleeping sickness is transmitted by the tsetse fly when it bites with the proboscis, while the causative agent of Chagas disease is transmitted through the feces of predatory bugs. The smallest skin lesions are sufficient to give Trypanosoma cruzei access to the human organism and blood vessels.

In vertebrates, trypanosomes usually live in the blood plasma, in the lymph or even in the cerebrospinal fluid. The pathogens causing sleeping sickness have developed a sophisticated system of changing antigen expression on their surface. As soon as the adaptive immune system has adjusted to the antigen type, it is confronted with a changed antigen to which the immune system first has to adjust itself again in a complex process.

Trypanosoma cruzi takes a different approach to evade the immune response. The pathogen changes into an amastigote form and multiplies inside the host cells in order to escape the attention of the immune system.

In trypanosomes transmitted by biting flies, a swelling, also known as a trypanosome chancre, typically develops at the puncture site. About two weeks after infection, the pathogens enter the blood and lymph vessels. The lymph nodes swell and - if left untreated - periodic attacks of fever occur. In some cases, sometimes it takes years for the pathogens to cross the blood-brain barrier and trigger meningitis in the central nervous system (CNS).

In principle, a distinction must be made between East African sleeping sickness and West African sleeping sickness due to the different host changes. Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (East African sleeping sickness) is, strictly speaking, the causative agent of a zoonosis, since animals such as antelopes, springboks and other savannah dwellers form the main reservoirs without becoming ill themselves. Tsetse flies then mainly become infected in wild animals and pass the pathogen on to humans without going through the usual generation change in tsetse flies. De facto, it is an infection from wild or farm animals to humans. It is noteworthy that both the female and the male tsetse fly act as a vector (vector). In contrast, the transmission of the malaria pathogen to humans occurs exclusively through the female Anopheles mosquito.

Illnesses & ailments

Of the multitude of trypanosome species that exist worldwide, only three occur as pathogens for humans. Specifically, these are the pathogens of West African and East African sleeping sickness and the pathogen of Chagas disease, which is widespread in countries in Central America and northern South America.

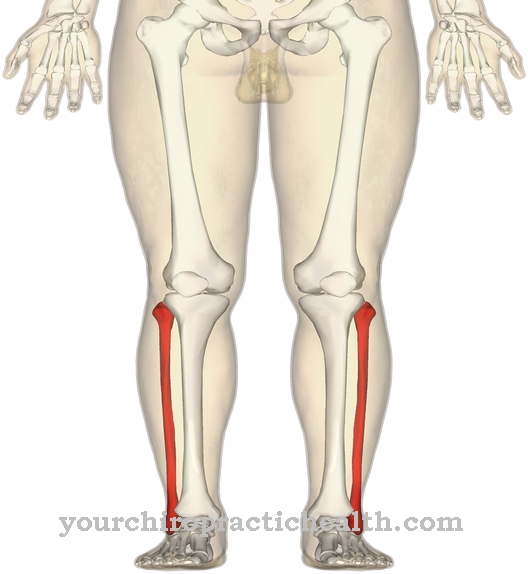

The risk of developing a trypanosome infection is limited to the regions where tsetse flies are native and to Central America. The pathogens of Chagas disease are not transmitted by flies or mosquitoes, but by a certain type of predatory bugs, which the sporozoites do not transmit during the blood meal, but excrete with the feces. The sporozoites can enter the body via a smear infection, where they attack the heart muscles, the supporting nerve tissue (neuroglia) and certain cells of the immune system.

If left untreated, Chagas disease has several phases and is fatal for about 10 percent of infected people. There is an increased risk of infection for young children and for people with naturally or artificially weakened immune systems. After the approximately three-week incubation period, the first symptoms appear, such as skin changes, constant or relapsing fever and swollen lymph nodes. The symptoms during this acute phase are very similar to those of a flu-like infection. A local skin reaction called a chagom develops at the point of entry of the pathogen.

.jpg)