The Argyll Robertson Sign is a reflex pupillary rigidity with intact near accommodation of the eyes. A midbrain lesion negates the light responsiveness of one or both eyes. This phenomenon plays a role in diseases such as neurolues.

What is the Argyll-Robertson Sign?

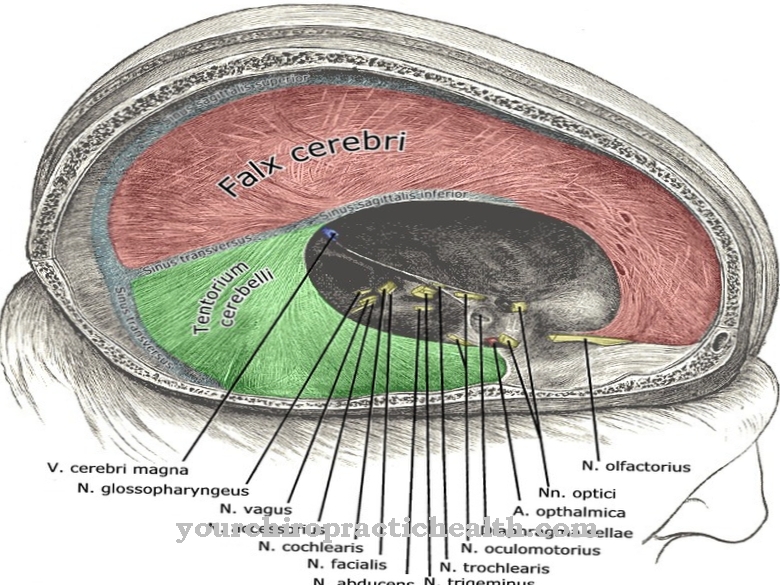

The midbrain is the part of the brain stem between the bridge (pons) and the interbrain (diencephalon). In this area of the brain, the muscles of the eye are primarily controlled.

The midbrain belongs to the so-called extrapyramidal system, which cannot always be clearly separated from the pyramidal system of movement control. The extrapyramidal system is a neurophysiological concept for all movement control processes outside the pyramidal tracts in the spinal cord. The excitations of the sensitive midbrain nerves are transferred from the diencephalon to the cerebrum (telencephalon), where they are switched to motor nerves. The structure of the midbrain is three-tiered. The so-called cerebral canal, which is filled with liquor, lies between the roof of the midbrain (tectum mesencephali) and the tegmentum.

The Argyll-Robertson sign is an indication of a cerebral disorder in the midbrain, which manifests itself in a reflex pupillary rigidity. The pathological phenomenon was named after the Scottish ophthalmologist D. Argyll Robertson, who first described it in the 19th century.

Function & task

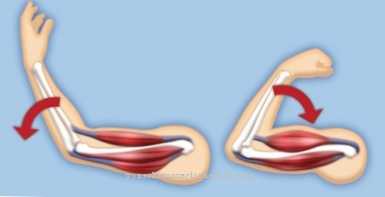

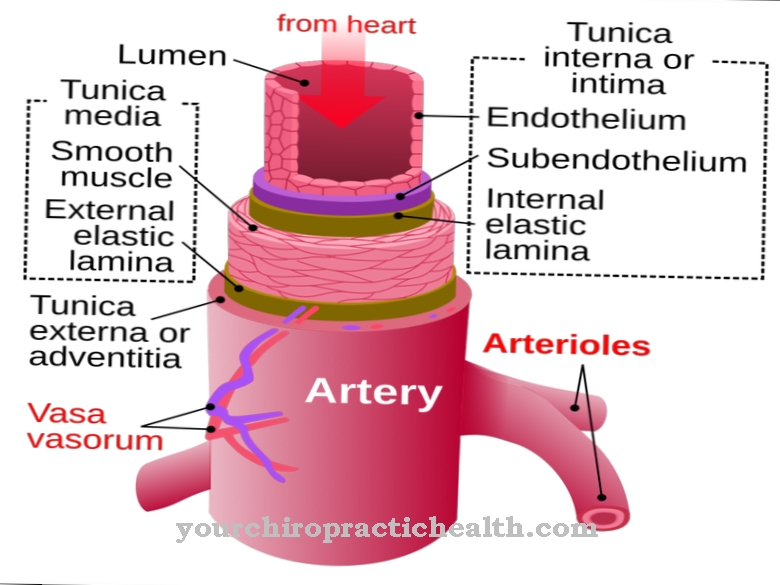

The eyes are able to adapt to light conditions in the field of vision. This adaptation is also called adaptation. The most important movements in this context are the pupillary light reflexes. The iris delimits the pupil. The pupillary light reflexes result from a change in tone in the smooth iris muscles. This change in the tone of the iris changes the pupil size and adapts the pupils to the relative amount of incident light. These processes are comparable to adjusting the aperture width on the camera.

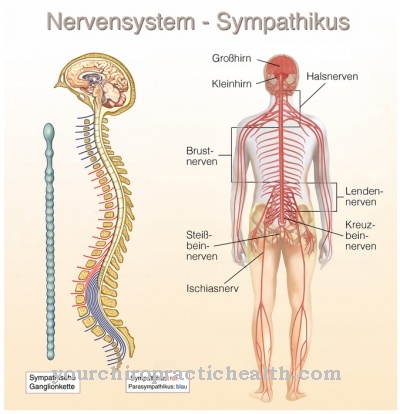

The iris muscles involved are the dilatator pupillae and the sphincter pupillae muscles. The dilator pupillae muscle is also called the pupil dilator. It is attached to the nervous system by sympathetic nerve fibers that originate in the centrum ciliospinale and thus the spinal cord segments C8 to Th3. If the pupils are enlarged unnaturally by this muscle or independently of light stimuli, it is called mydriasis.

The sphincter pupillae muscle is also called the pupil constrictor. It is innervated by parasympathetic nerve fibers from the third cranial nerve (oculomotor nerve) rather than sympathetic nerve fibers. The fibers come from the Edinger-Westphal nucleus and run over the ciliary ganglion. The activation of these regions takes place with particularly strong incidence of light and narrows the pupils. A pathological narrowing is called miosis. The incidence of light at the pupil is regulated by these muscles and nerves. An external stimulus therefore causes a muscle contraction and adapts the eye to a sudden change in brightness.

The reflex chain is subject to a perfectly coordinated connection. The nerve tracts of the central nervous system are also called afferents. They are the first point of the eye reflexes. Increased incidence of light is registered by the light-sensitive sensory cells of the retina. These photoreceptors convey the information via the sensitive optic nerve (nervus opticus) and the tractus opticus into the epithalamus, where they reach the nuclei praetectales. Efferents emanate from these nuclei and guide information back out of the central nervous system.

In this way, the information about the brightness is passed into the Edinger Westphal cores via efferent paths. In the nuclei, the information is switched to the parasympathetic part of the oculomotor nerve. They migrate over the ciliary ganglion and thus stimulate the sphincter pupillae muscle to contract. This narrows the pupil.

From each eye there is a connection to both pretectal nuclei. Therefore, a pupillary reflex is always carried out on both sides, even if only one side is illuminated.

Illnesses & ailments

The Argyll-Robertson-Sign plays a role especially for the neurologist. It is a matter of the loss of the direct and indirect pupillary light reaction described above. The doctor checks the reflex pupil adaptation with the help of a light as part of the neurological examination.

The Argyll-Robertson sign is a bilateral disorder and manifests itself after exposure to light in equally narrow, rounded pupils that no longer react or only react poorly. Since the convergence reaction of the eye is intact, the pupils nonetheless narrow during near accommodation. So if only the light pupil reflexes, but not the near accommodation processes, are abolished, the Argyll-Robertson sign is present. The convergence reaction of the eye is retained, which means that the eye is still able to adapt when objects are fixed.

This convergence reaction is mediated by the oculomotor nerve. Damage to the cranial nerve as a cause of the Argyll-Robertson phenomenon is thus excluded and the doctor suspects midbrain lesions. The connection between the Edinger-Westphal nucleus and the nucleus praetectalis olivaris is probably affected by damage.

The causal relationships are often lesions of a neurolue. This is a form of syphilis. The infectious disease spreads to the central nervous system and can cause paralysis and failures of the cranial nerves and spinal degeneration. The Argyll-Robertson sign is usually associated with a late stage of neurolues and is rated as one of the most important indicators of this disease.

However, midbrain lesions and the phenomenon of pupillary rigidity do not necessarily have to be associated with syphilis. Multiple sclerosis and other neurological diseases can also cause brain lesions in the midbrain, for example. The further clinical picture can be extremely diverse, depending on the overall affected brain region.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)