The chondral ossification refers to the bone formation from cartilage tissue. In addition to desmal ossification, it represents one of the two basic forms of bone formation. A well-known disorder of chondral ossification is achondroplasia (short stature).

What is chondral ossification?

In contrast to desmal ossification, chondral ossification describes indirect bone formation. While in desmal ossification embryonic connective tissue is converted into bone substance, in chondral ossification the bone formation takes place via an initially built up cartilage skeleton. During this process, the cartilage tissue is broken down parallel to the bone structure.

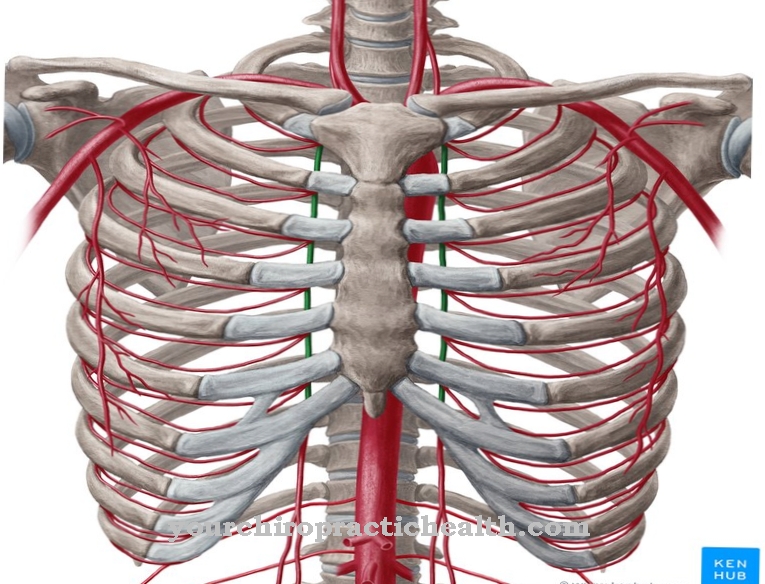

Furthermore, a distinction is made between perichondral and enchondral ossification. Perichondral ossification, for example, characterizes an ossification on the diaphysis (shaft) of the bone that leads from the outside to the inside. In enchondral ossification, ossification occurs from within. It usually takes place on the epiphyseal plates and is responsible for the longitudinal growth of the bones as long as the epiphyseal plates are still open.

However, once the ossification is complete, the epiphyseal plates close. The longitudinal growth of the bones then comes to a standstill. This state marks the end of the human growth process. Now there is only a growth in the thickness of the bones on the diaphysis due to the perichondral ossification.

Function & task

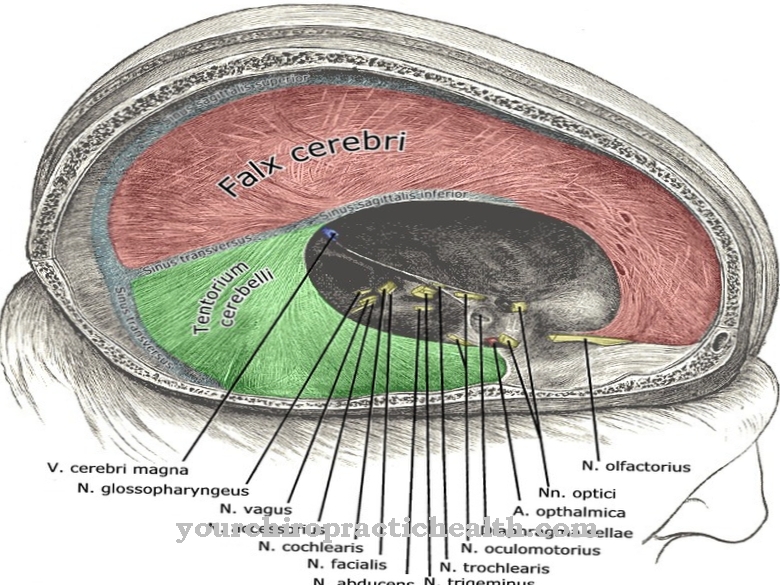

The chondral ossification is almost responsible for the structure of the entire bone skeleton. Only the bones of the roof of the skull, the facial skull and the clavicle are built up via desmal ossification.

In chondral ossification, the human skeleton is initially built up as a cartilage skeleton during embryogenesis. Therefore, these bones are also called replacement bones. In the course of further development, this cartilage tissue becomes ossified. The ossification is only completely completed with the end of the human growth process. With the complete transformation of cartilage tissue into bone tissue on the epiphyses, the last epiphyseal plates close. The length growth of the bones and thus the entire human growth comes to an end.

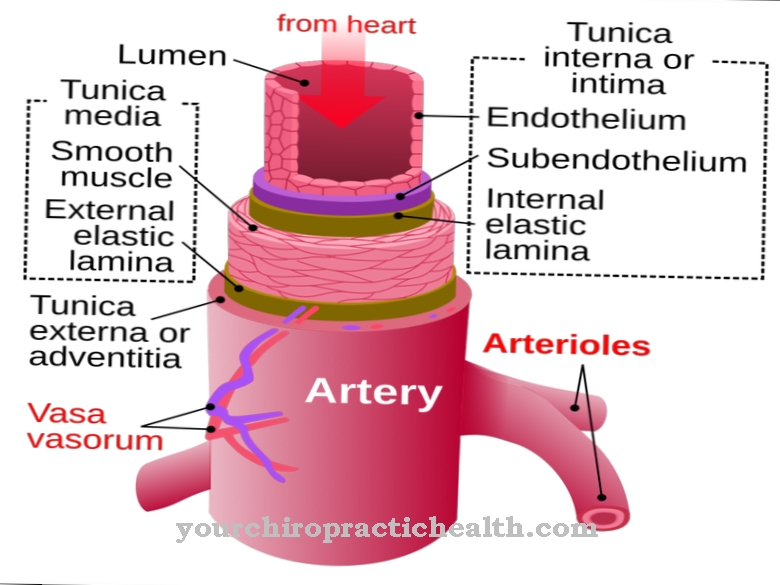

The chondral ossification can be divided into two forms. As already mentioned, a distinction is made between perichondral and enchondral ossification. Perichondral ossification usually takes place on the bone shaft (diaphysis). In the course of this process, osteoblasts are formed on the outer bone skin, which attach themselves in a ring around the cartilage model. This creates a bone cuff around the cartilage. The ossification migrates from the outside to the inside. Inside, the cartilage tissue is broken down by chondroclasts, while at the same time additional bone tissue is built up by osteoblasts. The cartilage tissue becomes ossified and the bone thickens at the same time.

The enchondral ossification begins inside the cartilage tissue. For this purpose, blood vessels grow into the cartilage tissue, which are accompanied by mesenchymal cells. These mesenchymal cells also differentiate into chondroclasts and osteoblasts. The chondroclasts constantly break down cartilage cells while the osteoblasts build up bone cells. Enchondral ossification occurs mainly on the epiphyses. As long as the epiphyses consist of cartilage tissue, the epiphyseal plates are open. Due to the bone growth from the inside, however, the bone cells expand in the longitudinal direction because the joints do not allow any growth in width or size. The growth in length of the bones is therefore the result of evasive growth. Only when the epiphyses are ossified do the epiphyseal plates also close. Then the growth in length finally comes to a standstill.

After that, bone growth only takes place after bone fractures or injuries. However, bone cells are formed and broken down again for a lifetime.

In chondral ossification, as in desmal ossification, bone cells arise from the mesenchyme. However, with the chondral form of bone formation, a cartilage skeleton is first built up, which already fulfills the most important basic functions of a bone skeleton. The actual bone formation takes place here as a second step, with the cartilage tissue then being remodeled into bone tissue. The cartilage cells break down and the bone cells build up at the same time.

Illnesses & ailments

In the context of chondral ossification, disorders can occur that have a significant impact on bone growth. A typical growth disorder is so-called achondroplasia. In achondroplasia, the epiphyseal plates are closed prematurely. The bones stop growing in length. However, the growth in thickness of the bones does not stop. At the same time, the desmal ossification continues so that the head continues to grow normally. The rib bones and vertebrae are also not affected by the closure of the epiphyseal plates. Because of this different growth, there are shifts in the body proportions: the trunk and head grow normally, with the length growth of the extremities coming to a premature standstill. This growth disorder is genetic. However, it does not have any negative effects on health.

Another disorder of chondral ossification manifests itself in excessive bone formation. This clinical picture is also known as heterotopic ossification. The term expresses that bone formation takes place in a different place than usual. This leads to ossification in places where only connective tissue should actually be present. This heterotopic ossification is often triggered by accidents and injuries. The tissue damage animates the body to produce messenger substances that can induce the conversion of bone precursor cells via cartilage into bones. Usually this additional bone formation does not lead to further complaints.

A genetic disease that leads to progressive fossilization is Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Here, the entire connective and supporting tissue of the body is gradually converted into bones.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)