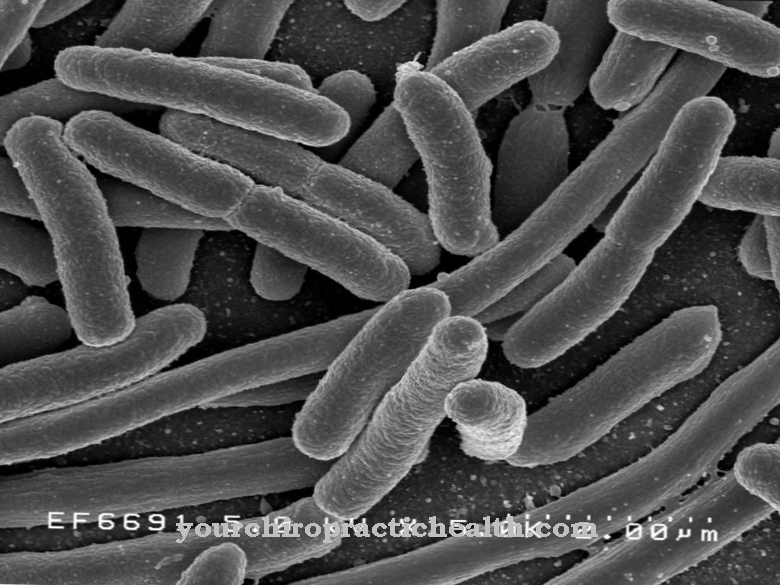

As Escherichia is a genus of gram-negative, rod-shaped bacteria. Its most important representative and most relevant to human pathogens is Escherichia coli (E. coli). Escherichia belong to the enterobacteria and make up a small proportion of the normal flora of the intestine.

What are escherichia?

Escherichia are gram-negative rod bacteria that occur physiologically in the intestinal flora of humans. They grow facultatively anaerobically, which means that they can grow and reproduce both with and without the presence of oxygen. They are also oxidase negative. The Escherichia are flagellated bacteria, so they are mobile. A selective cultivation of Escherichia is possible on culture media containing bile salts such as McConkey agar.

E. coli, a type of Escherichia, is the most common pathogen of bacterial infection and also serves as an indicator germ for contaminated drinking and bathing water. Research on E. coli won numerous scientists the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine. Other species of Escherichia such as E. hermanii or E. vulneris are known, but infections with them are very rare.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

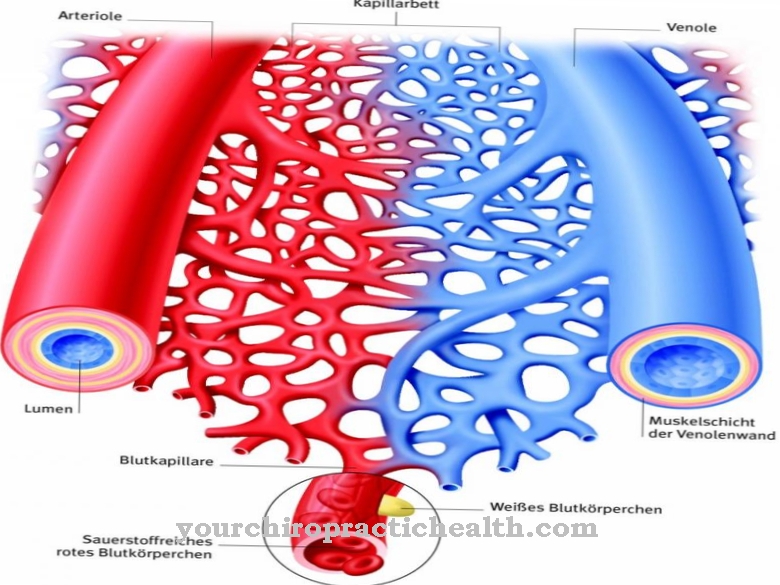

Escherichia belong to the group of enterobacteria, which means that they are mainly found in the intestines of mammals. E. coli mainly plays a role in human medicine. If a person comes into contact with substances from their intestines, it can contaminate drinking water or food, for example, which can subsequently infect other people. That is why E. coli is regarded as a faecal indicator, there must be no E. coli in 100 ml of drinking water. In addition, inadequate hygiene in public toilets promotes urinary tract infection, especially in women.

Various agglutination reactions with known antisera can be used to detect various antigenic structures on the surface of the Escherichia, which is referred to as serotyping. This results in an individual antigen pattern. A distinction is made between O-antigens (surface antigens, which corresponds to lipopolysaccharides), H-antigens (flagellin of the flagella, a thermostable protein), K-antigens (carbohydrates of the outermost membrane) and F-antigens (fimbriae). The fimbriae are there to attach to the lining of the gastrointestinal tract.

Escherichia also have no capsule and are peritrich (completely around the whole cell) flagellated, so they are mobile. This is especially important for E. coli, because when it is in the stomach it cannot expose itself to the aggressive gastric acid and therefore moves into the protective mucus.

A distinction is made between different subtypes of E. coli, each of which develops different virulence factors and causes different diseases. These are also known as pathovars: The EPEC (= enteropathogenic E. coli) attaches to the intestinal mucosa and can inject a toxin into the cells via what is known as a type 3 secretion system. This toxin causes the intestinal epithelium to flatten. They mainly affect infants and are responsible for the rare infant diarrhea.

ETEC (= enterotoxic E. coli) also produces two enterotoxins. It is the causative agent of traveler's diarrhea, which is triggered by foodstuffs contaminated orally, especially in the tropics. The clinical picture is similar to that of cholera, as the two toxins correspond to one another.

EHEC (= enterohaemorrhagic E. coli) has the protein intimin, which promotes a firm binding of the bacteria to the intestinal mucosa. The pathogen also forms a toxin that is similar to the shigatoxin produced by Shigella. This leads to the inhibition of protein synthesis in the affected cells. They are also known as STEC (= Shiga toxin-producing E. coli).

The EAEC (= enteroaggregative E. coli) is able to form aggregates with other bacteria that linger on the intestinal mucosa. UPEC (= uropathogenic E. coli) expresses the P-fimbriae on its surface, which is used specifically for binding to the epithelium of the urogenital tract. The EIEC (= enteroinvasive E. coli) penetrates directly into the intestinal epithelial cell and spreads to neighboring cells by invading them directly.

Illnesses & ailments

In Escherichia, a distinction is made between intestinal infections, i.e. diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (which are always caused by exogenous infections) and extraintestinal diseases, which are mostly caused by endogenous infections.

E. coli are the most common causes of bacterial infection. The different subtypes trigger different diseases: EPEC is responsible for infant diarrhea, which is characterized by massive diarrhea and the risk of dehydration. In the third world, the pathogen is the cause of high infant mortality rates. The causative agent for chronic persistent diarrhea is the EAEC. The diarrhea is slimy because it induces the intestinal mucosa to secrete more mucus.

The causative agent of traveler's diarrhea is ETEC, which is very similar to cholera. Diarrhea similar to rice water of up to 20 liters a day is not uncommon. The EHEC, which is also the most well-known subtype, is responsible for watery to bloody diarrhea, which can be responsible for a hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), especially in small children, which can lead to kidney failure. Fever, stomach cramps and vomiting can also be considered. Another complication can be a perforation of the intestine.

EIEC is the causative agent of dysentery-like colitis with bloody, slimy diarrhea. UPEC, as the causative agent of an extraintestinal infection, causes urinary tract infections when the bacterium enters the urogenital tract from the intestine. This is especially the case in women due to the anatomical proximity of the anus to the urethra. They can also cause meningitis in the newborn, as the birth canal is also near the anus and can thus infect the child during birth.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)