The parenteral or non-oral administration of heparin for the purpose of the coagulation inhibition of the blood is Heparinization called. Either the less rapidly acting low molecular weight heparin is used for the prophylaxis of thromboses and embolisms or the unfractionated heparin for the treatment of thromboses and embolisms.

The most common indications for the preventive use of the classic anticoagulant are operations, atrial fibrillation and artificial heart valves made of non-biological material.

What is heparinization?

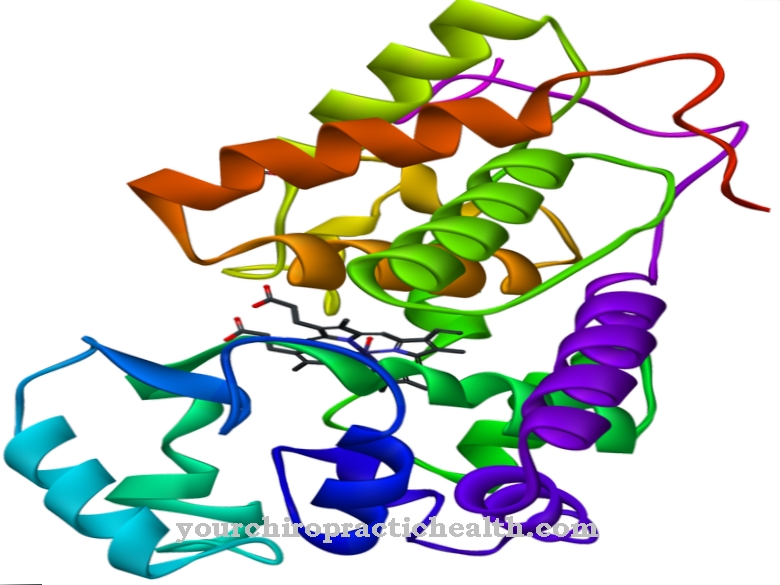

Heparins are polysaccharides that belong to the glycosaminoglycans with a variable number of aminosaccharides. Heparins with a chain length of more than five monosaccharides have an anticoagulant effect.

With a chain length of 5 to 17 monosaccharides they are called low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) and from a chain length of 18 or more monosaccharides they are called unfractionated heparins (UFH). LMWH and UFH have the property of binding certain thrombins very effectively, so that the coagulation cascade is interrupted and explains the anticoagulant properties of the heparins. When administering heparin, medical parlance usually distinguishes between complete heparinization with UFH and heparinization with LMWH. Full heparinization with UFH (optionally also with LMWH) is used to treat acute embolism or thrombosis.

Heparinization with the slower acting NHM is a precautionary safety measure in situations or conditions that could provoke blood clots to form. In laboratory medicine, the term full heparinization refers to the addition of heparin to whole blood samples and the wetting of devices that come into contact with blood in order to prevent coagulation.

Function, effect & goals

Blood clotting is a complex process in which a number of coagulation factors are involved, which are supposed to ensure that blood does not clot in the wrong place at the wrong time. In the case of external injuries, the situation is still relatively simple because the presence of molecular oxygen in the air can accelerate coagulation.

In the case of internal bleeding, it is much more difficult to control the necessary coagulation in order to distinguish internal bleeding, in which coagulation is essential, from other situations in which blood has to flow through narrowed vessels. In this case, coagulation that leads to thrombus formation might not be life-saving, but life-threatening. Nevertheless, certain situations are predestined for the formation of thrombi, which can cause a thrombosis in one place or an embolism if it is spread elsewhere. In those cases in which there are known risks for the development of thrombi, a relatively low dose of heparinization with mostly low molecular weight heparin is carried out for prophylactic reasons.

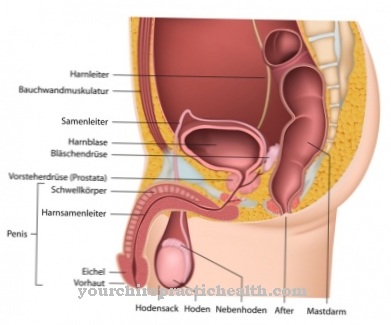

The anticoagulant effect is intended to counteract the formation of thrombi, which could lead to thrombosis, embolism, heart attack or a stroke. The necessary heparin must not be supplied orally because the heparin cannot be absorbed by the digestive system. Therefore, heparin is usually injected subcutaneously or intravenously.

Evidently evolution did not consider this possibility to be important, because the body itself synthesizes the required amount of heparin - mainly by the mast cells of the immune system - but the blood plasma cannot naturally reach a concentration that would be sufficient for prophylaxis. Typically, heparinization is performed before and after surgery and if atrial fibrillation persists.

In the case of artificial heart valves that are not made of biological material, lifelong heparinization or another suitable form of anticoagulation is recommended. In addition, there is a large number of other indications for which heparinization is recommended. Almost all other indications can be associated with thromboses, embolisms or local infarctions that have already occurred and have been treated. In the case of full heparinization with unfractionated heparins, the partial thromboplastin time must be checked in order to be able to set the correct dosage.

Risks, side effects & dangers

Complete heparinization with UFH ultimately always involves walking a certain tightrope between overdosing and underdosing. Underdosing ultimately offers too little preventive effect against the formation of thrombi and thus insufficient protection against thrombosis, embolism, myocardial infarction and stroke, without the fact that the facts are noticed unless the thromboplastin time is checked, which allows conclusions to be drawn about the coagulation protection.

Overdosing is immediately more problematic because it can lead to internal bleeding. With heparinization - especially with UFH - heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) of type I or II can develop in rare cases.Type I HIT is associated with a temporary decrease in the platelet count, which usually increases again automatically, so that no specific treatment is usually necessary. Type II HIT, which occurs when the immune system reacts to the heparinization with antibodies, is much more problematic. On the one hand, the number of platelets drops to less than half of the normal value and the heparinization effect is reversed.

The tendency for blood to clot is not inhibited, but increased, so that the risk of thrombosis or embolism increases. Long-term treatment with heparin can lead to osteoporotic effects with measurably reduced bone density and vertebral body fractures. If one of the serious side effects is noticed, the heparin must be discontinued and another anticoagulant must be used.

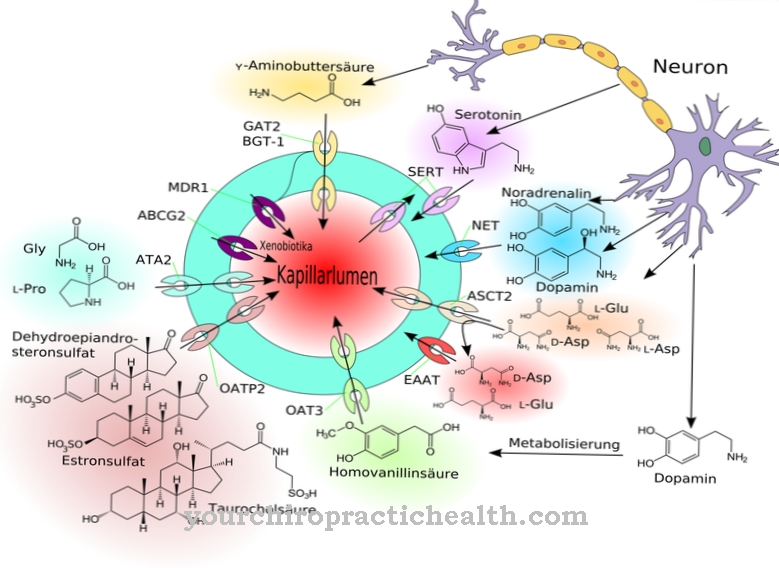

A rare side effect of heparinization is a reversible increase in transaminases in the blood plasma, which is usually an indication of damage to the liver or heart. Transaminases play an important role in the metabolism of amino acids for the transfer of amino groups. Transaminases are usually found in the cytosol of cells rather than as free enzymes in the blood.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)