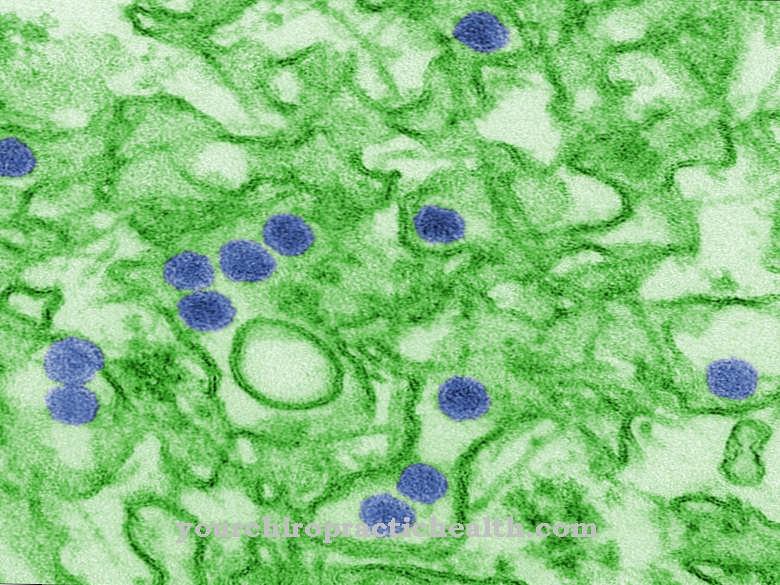

Leishmania brasiliensis are small, flagellated protozoa belonging to the Leishmania bacterial strain, subgenus Viannia. They live parasitically in macrophages, into which they have phagocytosed without being damaged. They are the cause of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and require a host change via the sand fly of the genus Lutzomyia in order to spread it.

What is Leishmania brasiliensis?

Leishmania brasiliensis is the main causative agent of American cutaneous leishmaniasis. It is a very small flagellated bacterium from the Leishmania family, which is equipped with a cell nucleus and its own genetic material, so that it is also assigned to the large group of protozoa.

Leishmania brasiliensis is the main causative agent of American cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is comparable to cutaneous leishmaniasis, which is caused, for example, by Leishmania tropica in other regions.

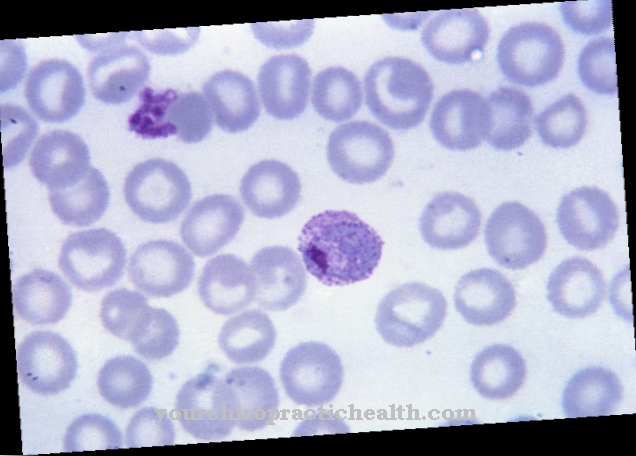

The bacterium lives parasitically intracellularly in protected small vacuoles in the cytoplasm of macrophages. They multiply within the macrophages by division and convert into the amastigote (flagellate) form. After the programmed cell death (apoptosis) of the infected macrophages, they are released in the tissue and phagocytosed, along with the fragments of "their" macrophages, unnoticed by other macrophages, without being lysed, i.e. without lysosomes, the weapons of the macrophages, passing their decomposing substances over the Empty bacteria.

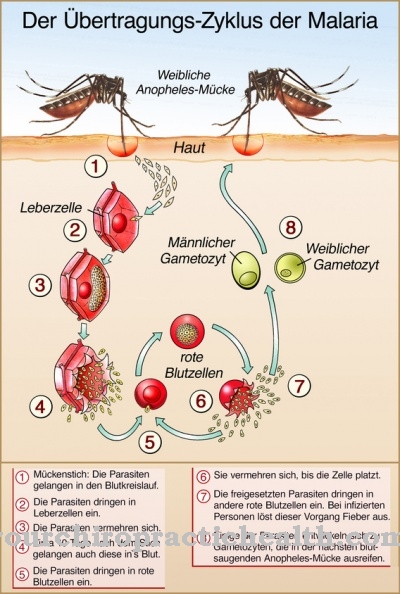

The spread of the bacteria occurs via host change with the blood-sucking sand fly of the genus Lutzomyia.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

Leishmania brasiliensis is - as its name suggests - widespread in South and Central America up to and including Mexico. What is noticeable about the pathogen is that, due to its characteristic intracellular form of life in the macrophages, it cannot spread to other people and thus ensure its own survival. For this purpose, Leishmania brasiliensis needs the sand fly of the genus Lutzomyia as an intermediate host.

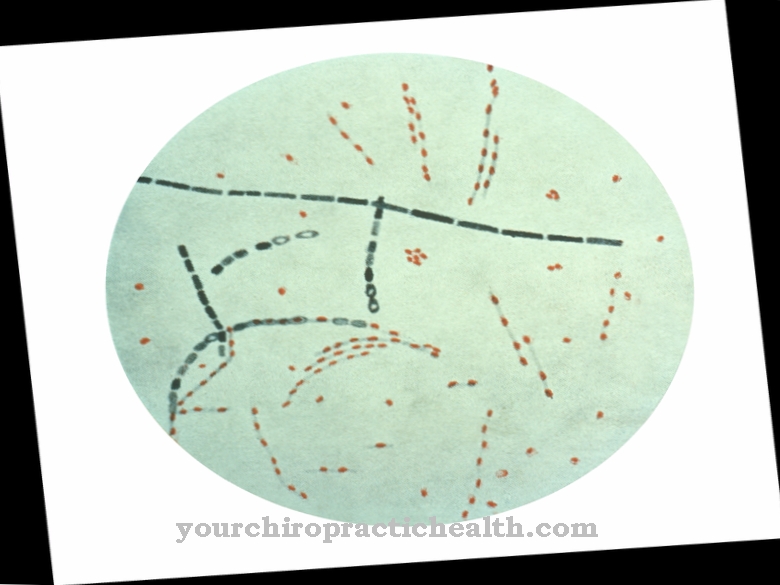

The blood-sucking mosquito ingests macrophages infected with the blood, which are digested in the mosquito's intestines and release the amastigotic leishmania. They then transform into the flagellated (promastigote) form and actively move towards the mosquito's biting apparatus.If you bite again with your proboscis, the pathogens get into the skin tissue of the stung person and are recognized as foreign by the first wave of the immune system and phagocytosed by polymorphic neutrophil granulocytes (PMN).

In order to avoid the lysis that usually takes place afterwards, the pathogens release certain chemokines that prevent the granulocytes from lysing. In addition, they know how to extend the life of “their” granulocytes from two to three hours to two to three days until the macrophages, which are also the actual host cells of the pathogen, are also attracted by cytokines.

Interestingly, the leishmanias support PMN in attracting macrophages, but at the same time prevent other species of white blood cells such as monocytes and NK cells (natural killer cells) from being attracted.

After apoptosis, the programmed cell death of the PMN, the macrophages phagocytose the fragments of the PMN and take the leishmanias with them without being noticed. As with phagocytosis by granulocytes, the macrophages do not undergo subsequent lysis of the bacteria so that they can develop and multiply intracellularly. The leishmanias know how to switch off an important immune response, lysis after phagocytosis, and how to use macrophages to protect it.

The pathogens ensure their survival by changing hosts with the sand fly, which is also associated with a relatively minor change in shape from the promastigote to the amastigote form. However, the Leishmanias depend on the human cycle or any other vertebrate and sand fly never being interrupted, as there is no form of the bacterium that would be able to survive outside of the two hosts.

Illnesses & ailments

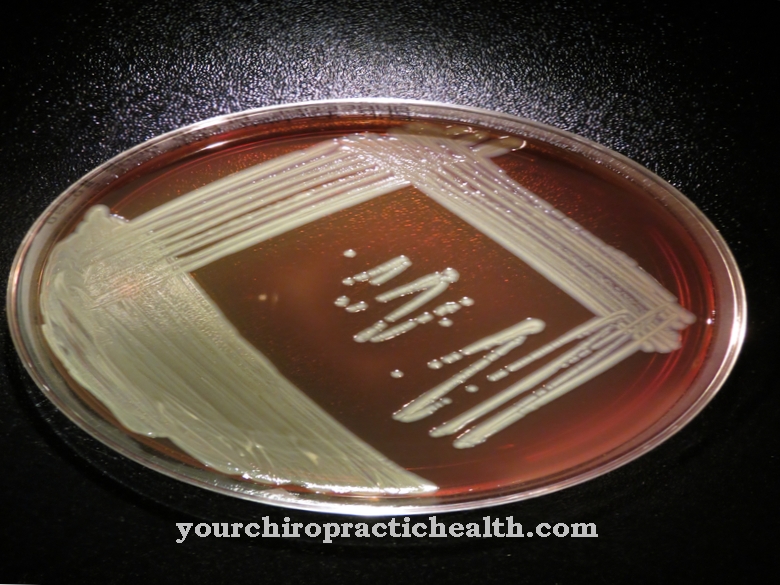

An infection with Leishmania brasiliensis with an incubation period of two to three months on average triggers American cutaneous leishmaniasis, which mainly occurs in three different forms. Most often, the disease manifests itself in the purely cutaneous form, which is also known as wart-shaped leishmaniasis.

First, a papule forms near the puncture site, which within a few weeks grows into one or more painless ulcers. Flat, slightly unsightly skin lesions form, which become scarred over time. In most cases, cutaneous leishmaniasis heals on its own within a few months without acquiring immunity to the pathogen.

In less common cases, there is an additional infection of the mucous membranes (mucocutaneous leishmaniasis). The pathogen usually colonizes the mucous membranes of the nasopharynx. The first symptoms are a permanently blocked or runny nose with frequent nosebleeds. If left untreated, this form of leishmaniasis can lead to serious ulcers and tissue changes in the nasopharynx as well as to a breakdown of the nasal septum.

Overall, the untreated mucocutaneous form of leishmaniasis has a poor prognosis. The ability of the pathogen to manipulate the immune system and thus mostly survive phagocytosis makes it possible for the bacteria to be transported to other regions of the body in the bloodstream or with the lymph. It is then about disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis.

This form of the disease can be recognized by skin lesions and papules that present themselves differently in different body regions. In rare cases, the pathogen travels via the lymph to internal organs such as the liver and spleen and causes the visceral form of leishmaniasis.

.jpg)