The two Thyroid hormones T3 (also triiodothyronine) and L4 (also L-thyroxine or levothyroxine) are produced in the epithelial cells of the thyroid gland. Their control is subject to the regulating hormone TSH basal (thyroid-stimulating hormone or thyrotropin), which is formed in the pituitary gland (pituitary gland). The classic thyroid diseases that are related to hormones are over- and underactive as well as autoimmune diseases.

What are thyroid hormones?

With regard to the hormones that affect thyroid function, a distinction must be made between the T3 and T4 produced in the thyroid gland itself and the TSH produced in the pituitary gland. The thyroid hormone T3 is also known as triiodothyronine. Part of it is formed directly in the thyroid gland, and part of it is made available to the body continuously by converting the thyroid hormone T4 into T3. A distinction is made in the blood between the bound form, the so-called total T3, and the free form.

The fT3 occurs in a smaller proportion, but is particularly relevant for meaningful blood tests. The thyroid hormone T4 is also available in the free form, which is then referred to as fT4. T4 is the same as L-thyroxine or levothyroxine. The central regulation of the thyroid hormones takes place via the pituitary gland, which releases the control hormone TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone or thyrotropin). The hormone calcitonin is formed in the C cells of the thyroid gland, which due to its function is not one of the actual thyroid hormones.

Anatomy & structure

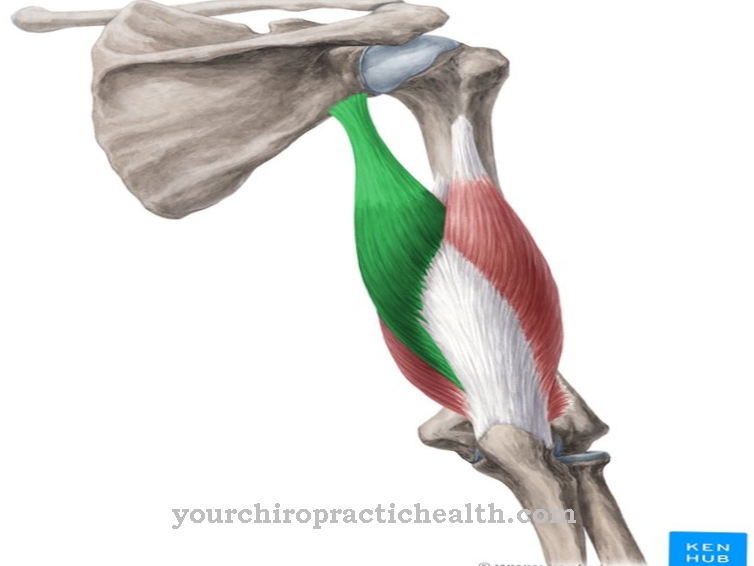

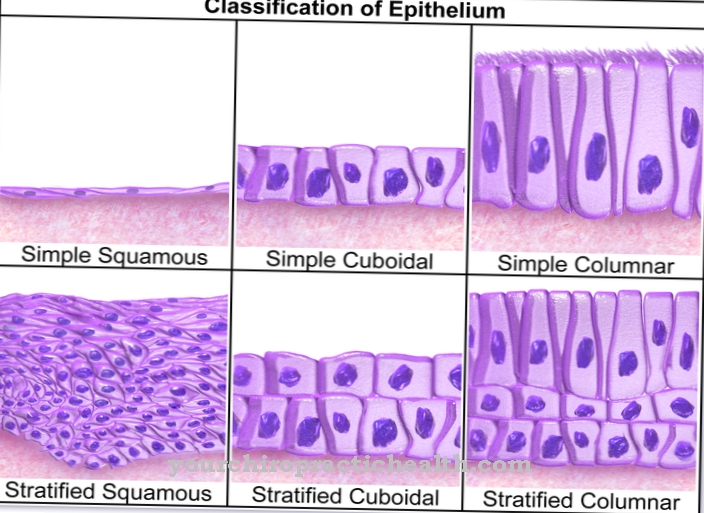

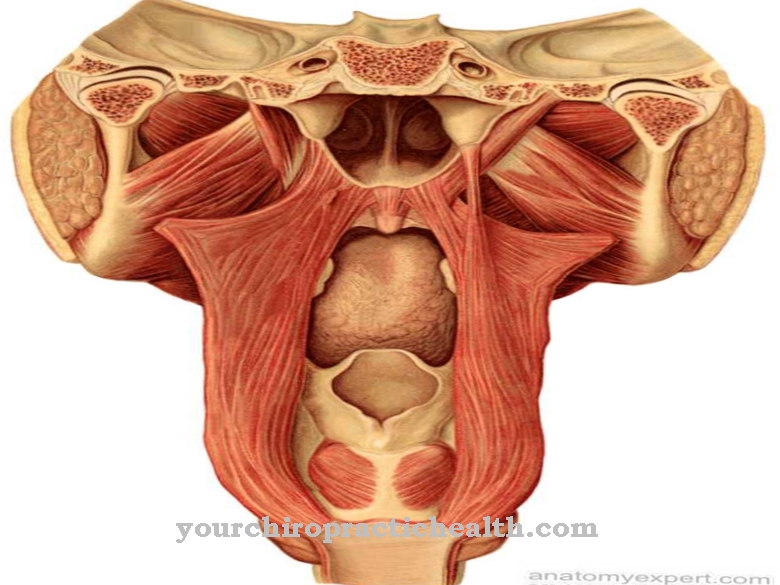

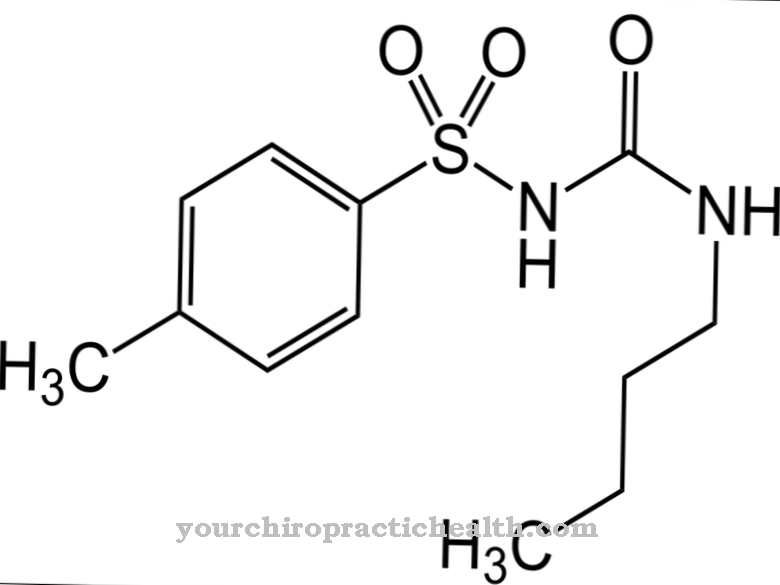

The classic thyroid hormones are known as T3 and T4 due to their molecular structure: The number 3 in triiodothyronine comes from the fact that the hormone has three iodine atoms in its structure. In L-thyroxine or levothyroxine there are four iodine atoms, hence the abbreviation T4. The formation of these two classic thyroid hormones takes place in the so-called thyrocytes, the follicular epithelial cells of the organ, which is located in the shape of a butterfly on the front of the neck below the larynx.

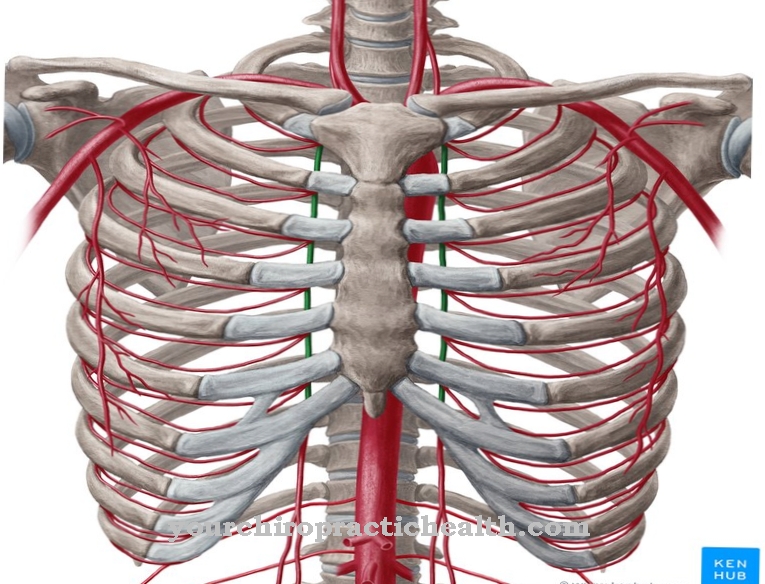

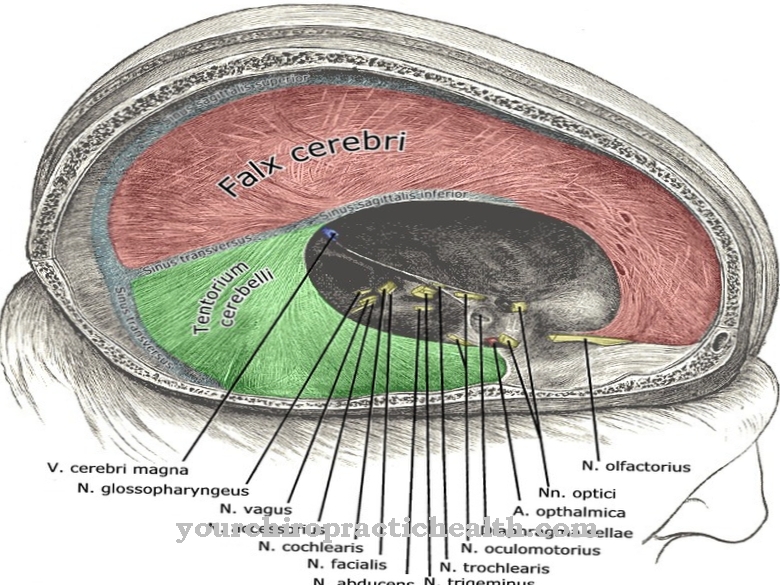

The TSH, on the other hand, is released through the pituitary gland - a hormonal gland located in the middle fossa. The pituitary gland is connected to the thyroid gland via a complex control circuit. It is also known as the thyrotropic control circuit and regulates the supply of thyroid hormones in the required concentration via the bloodstream.

Function & tasks

The tasks of the thyroid hormones are vital, so they have to be balanced for life in the event of an underactive organ or surgical removal. T3 and T4 have a multitude of functions that affect a wide variety of organ systems. They are significantly involved in numerous metabolic functions and serve to maintain a properly functioning organism.

Among other things, they ensure that the body receives the energy it needs for unrestricted performance. One of the reasons for this is that the thyroid hormones make their contribution to the body growing and its cells being able to mature unhindered - even in the fetus, by the way. For this reason, an optimal supply of hormones is particularly important for children and adolescents. The utilization of nutrients from food is also improved with the help of thyroid hormones.

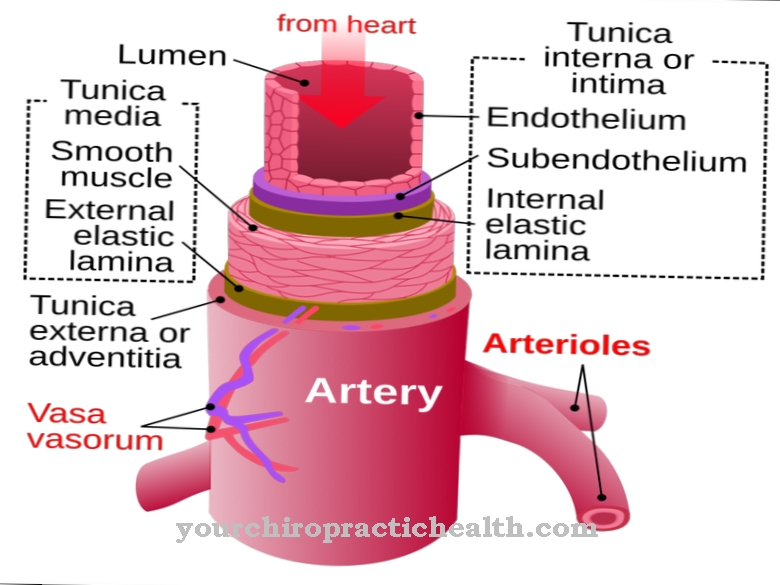

The hormones influence body temperature and the cardiovascular system, control mood and concentration and have a significant influence on fertility. In both T3 and T4, only the free portion that is not bound to transport proteins in the body is effective. In addition, the biological effectiveness of fT3 (free triiodothyronine) is several times higher than that of free T4.

The TSH, which regulates the processes centrally after its release from the pituitary gland, plays a major role. The thyroid-stimulating hormone migrates via a sensitive control mechanism from the pituitary to the thyroid gland, where it triggers the formation of T3 and T4. In another way, the thyroid hormones can, for their part, throttle TSH production in the pituitary gland as part of a negative feedback, so that, in the best case, a balance is achieved.

Diseases

Typical diseases that are related to thyroid hormones are the overactive or underactive thyroid as well as the autoimmune diseases Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Graves' disease. When the thyroid gland is overactive (hyperthyroidism), the thyroid gland works too much. The organism is running at full speed. Typical signs include sweating, palpitations and racing heart, diarrhea, weight loss with normal food consumption and an often unfounded nervousness.

On the basis of a blood test, hyperthyroidism can be recognized by an increased free T3 and T4 or a decreased TSH. In the case of hypothyroidism, the thyroid-specific laboratory values behave in reverse: The TSH is above the norm, the free T3 and T4 are too low. The physical and psychological symptoms behave accordingly: A patient with an overactive thyroid often unintentionally gains weight, freezes easily, is often tired and can suffer from constipation. Autoimmune diseases include Graves' disease and Hashimoto's thyroiditis. In Graves' disease, the body makes antibodies against its own thyroid tissue. It is therefore often associated with hypothyroidism, the underactive thyroid gland.

Other possible symptoms are the well-known goiter formation (goiter) in the lower area of the neck and endocrine orbitopathy, which is noticeable by clearly protruding eyes. There are two different variants of the disease in Hashimoto's thyroiditis. Both develop an underactive (hypothyroidism), whereby the initial destruction of the thyroid tissue can also initially show as overactive. If the thyroid gland has been removed, for example due to cancer or a disturbing goiter, a lifelong substitution with the vital thyroid hormones is necessary.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)