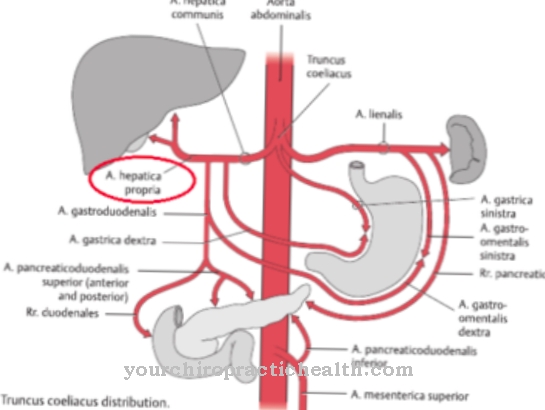

The Femoral artery represents the extension of the external pelvic artery and is used to supply the lower extremities. Four narrow-lumen vessels and the deep femoral artery branch off the artery, with a cross-section similar to that of the femoral artery. Because the artery is close to the surface of the skin, it is often used as an access artery for a left heart catheter.

What is the femoral artery?

The femoral artery, too Femoral artery called, runs just under the inguinal ligament (ligamentum inguinale) in direct extension of the external pelvic artery (arteria iliaca externa) and runs relatively close below the surface to the hollow of the knee, which it reaches through a gap in the broad tendon of the great thigh adductor and into the arteria poplitea , the popliteal artery.

The femoral artery can be seen as a direct extension of the main body artery, the aorta, which branches off into the two outer pelvic arteries at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. Because the femoral artery is ultimately a direct extension of the aorta and it runs superficially below the pelvis, the pulse can also be felt on it. The main branch of the femoral artery is the deep femoral artery, the deep femoral artery, which has a cross-section similar to that of the femoral artery.

Anatomy & structure

The femoral artery is counted among the large blood vessels and thus belongs to the type of elastic arteries. Its middle wall, the media, consists largely of elastic and collagen fibers. Smooth muscle fibers found in the media of the smaller muscular arteries are almost entirely absent from the femoral artery.

The femoral artery begins as an extension of the external pelvic artery and runs together with the femoral vein under the inguinal ligament. Immediately after passing the inguinal ligament, the deep femoral artery, the arteria femoralis externa, branches off. It has a cross-section comparable to that of the femoral artery. Four other arterial branches with a small cross-section arise from the femoral artery. The four branching arteries of small cross-section can be classified in the class of the mixed type because their median walls have features of the muscular and elastic types. The medias contain smooth muscle fibers, elastic fibers and, for stabilization, also collagen fibers.

Function & tasks

The primary task of the femoral artery is to supply the leg and parts of the lower body, including the genital area, with oxygen-rich arterial blood, which also contains the necessary nutrients in dissolved form. Secondly, the femoral artery, with its elastic walls, supports the aorta's function of the aorta.

The Windkessel function smooths the systolic blood pressure peaks and ensures that the residual diastolic pressure in the arteries is maintained so that the very narrow vessels, the arterioles and capillaries do not collapse and "stick" through adhesive forces so that they irreversibly lose their function. In detail, the femoral artery supplies not only the respective leg via its branching small arteries, but also other regions in the abdomen and upper abdomen as well as large parts of the groin region including the genitals.

The complex network of the knee and thigh is supplied via the branching descending artery, also known as the descending knee artery. Branches of the large branching large arteria profunda femoris supply the muscles on the flexor side of the thighs and the femoral head. Some of the smaller arteries form what are known as anastomoses with other small arteries. They connect with each other and network. In the event of a stenosis or a complete blockage, they can each take over part of the blood supply for the defective vessel, so that the tissue does not necessarily die immediately after a vessel blockage.

Diseases

The most common diseases or conditions associated with the femoral artery and its branching branches are deposits in the median wall of the artery.

This can lead to a narrowing of the cross-section, a stenosis or a complete blockage of the artery with the consequence that the tissue to be supplied is undersupplied. The reasons for the formation of deposits in the artery walls are very diverse. A disturbed cholesterol balance often plays a role. It is less about the absolute level of total cholesterol and more about the ratio of LDL (low density lipoprotein cholesterol) to HDL (high density lipoprotein cholesterol). The quotient should ideally not be above 3.5 to 4.0.

They are so-called transport proteins. LDL transports cholesterol to the membranes of the blood vessels and HDL transports unneeded cholesterol from the blood vessels back to the liver. Changes in the vessel walls can also be acquired through infections, heavy smoking or chronic alcohol consumption, for example. In less common cases, genetic defects inherited in an autosomal recessive or dominant manner lead to changes in the vessel walls. The changed physical behavior of the vessel walls can, for example, favor the formation of an aneurysm, a bulging of the artery.

Very rarely an aneurysm dissecans can develop in the femoral artery, which is caused by bleeding into the media, so that a “false” lumen is formed between the inner and outer wall layers. This can also block the artery. In accidents involving leg injuries, the femoral artery can be injured by external mechanical influences, causing profuse bleeding. If the bleeding cannot drain to the outside, very large hematomas may form.

.jpg)