Leishmania are human pathogenic protozoa. The parasites spread via two host organisms and change their host between insect and vertebrate. Infection with leishmania leads to leishmaniasis.

What are leishmanias?

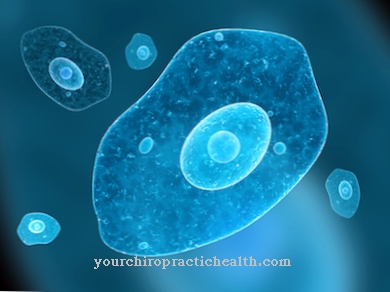

Protozoa are primeval animals or primeval animals which, due to their heterotrophic way of life and mobility, can be classified as animal eukaryotic unicellular organisms. According to Grell, they are eukaryotes that occur as single cells and can form colonial associations. Leishmania or Leishmania form a genus of flagellated protozoa that colonize the blood of macrophages and multiply there. In this context, there is also talk of hemoflagellates.

Leishmanias are obligatory intracellular parasites that switch host between insect species such as sandflies or butterfly mosquitoes and vertebrates such as sheep, dogs or humans. The parasite genus was named after William Boog Leishman, who is considered to be the first to describe it.

Like other flagellates, organisms of the genus Leishmania change the shape and position of their flagellum with their current host and stage of development. Basically, Leishmanias are small on average.

Parasites live and grow at the expense of their hosts. This means that parasites always have disease value and cause more or less severe damage to the host organism. Leishmanias, for example, cause the clinical picture of leishmaniasis and are generally considered to be pathogenic to humans.

The parasites have now spread from Australia all over the world and cause numerous animal diseases worldwide. Not all strains of the genus attack humans. Nevertheless, according to the WHO, around 1.5 million new cases occur worldwide each year. Around a third of this is the prevalence for visceral leishmaniasis. Twelve million people are currently considered to be carriers of the infection.

Occurrence, Distribution & Properties

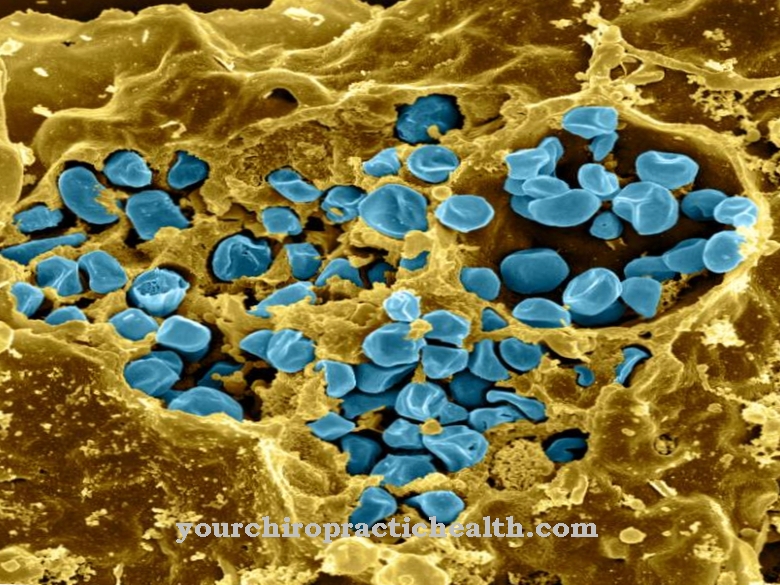

Leishmanias multiply in two hosts. The first place of reproduction is the sand fly organism. With the mosquito's saliva, they migrate to the stung organism in a flagellated form. In the organism of vertebrates they are phagocytosed by macrophages or phagocytes. This principle is also known as passive invasion and results in the transformation of leishmanias. With the silent invasion of the phagocytes, the organisms transform their form into an amastigote or ungodly form.

Within the macrophages, the parasites multiply by means of division. When they destroy the host cell, they return to amastigote form. In the flagellated form, the parasites are extraordinarily mobile and so able to invade new macrophages again. As soon as the pathogen is reabsorbed from the blood of an infected vertebrate by a sand fly or similar insect, the cycle closes. In the intestine of the insect, the leishmanias again become a promastigote organism, which becomes an amastigote form within the intestinal epithelium and thus reaches the mosquito's salivary glands. The next time a vertebrate stick, a new infection can occur.

One of the pathogenicity factors of Leishmania is the “Trojan horse” strategy. They carry a signal on their surface that suggests harmlessness to the immune system. The memory function is thus bypassed. In addition, the parasites of the species Leishmania major reverse the action of the defense reaction for their benefit. They use the phagocytosing neutrophilic granulocytes for their purpose by invading long-lived macrophages undetected and multiplying inside them.

When there is an infection in the tissue, granulocytes are attracted to the affected area by chemokines. In the case of an insect bite, this area corresponds to the skin. They phagocytize the invading organisms due to their surface structures and create a local inflammatory process. Activated gray cells then secrete chemokines in order to attract more granulocytes. The phagocytosed leishmanias promote the formation of further chemokines inside the phagocytes. The pathogens multiply undetected and unchecked in the infected tissue. Leishmania also produce chemokines themselves, which stop the formation of the interferon-inducible chemokine within the infected granulocytes and thus prevent the activation of the NK or Th1 cells.

Illnesses & ailments

The processes described above make leishmania infection a malicious disease. The leishmanias survive phagocytosis because their primary host cells signal the absence of pathogens to the immune system. The natural lifespan of granulocytes is short. Apoptosis begins after around ten hours. In granulocytes with the infection, caspase-3 activation is inhibited, so that they live up to three days longer. The pathogens also stimulate the granulocytes to attract macrophages, which clear cell toxins and proteolytic enzymes of the granulocytes from the surrounding tissue. The leishmanias are absorbed by macrophages via physiological clearing processes, with the absorption of the apoptotic material attenuating the macrophage activity.

Defense mechanisms against intracellular parasites are deactivated so that the pathogen survives. In the intracellular granulocytes, the pathogens have no direct macrophage surface receptor contact and remain unseen. The phagocytes of the immune system are not activated in this way.

In visceral leishmaniasis, the internal organs are affected. The most common pathogens are Leishmania donovani and infantum. Without therapy, around three percent of cases of illness end fatally. In skin leishmaniasis or cutaneous leishmaniasis, the internal organs are spared. The most important causative agents of this infection are Leishmania tropica major, tropica minor, tropica infantum and aethiopica.

The skin will redden after being transmitted by the insect. Itchy nodules form, gradually turning into papules and later forming an ulcer up to five centimeters. In addition to moist skin infections, dry or diffuse skin infections also occur. In addition to these forms of leishmaniasis, there is also mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, which affects the mucous membrane in addition to the skin.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)