The Tricuspid valve is one of the four heart valves. It forms the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle and prevents the blood from flowing back into the right atrium during the contraction of the ventricle (systole). During the relaxation phase (diastole) the tricuspid valve is open so that the blood can flow from the right atrium into the right ventricle.

What is the tricuspid valve?

The tricuspid valve is the heart valve, which acts as a valve between the right atrium and right ventricle and ensures that the blood is pumped into the pulmonary artery, into the pulmonary artery - also called the small circulation - and not back into the pulmonary artery during the tension phase of the right ventricle (systole) right atrium can flow.

The valve is closed during this process and only opens again during the relaxation phase of the right ventricle (diastole). Like its counterpart in the left ventricle, the tricuspid valve corresponds to a so-called leaflet valve, which in principle works passively like a non-return valve, but is muscularly supported by tendon threads on its leaflets.

It is part of the heart's four-valve system, with the help of which the closed blood circulation can only flow in one specific direction. The other two heart valves, the pulmonary valve and the aortic valve, are used to prevent the blood from flowing back from the arteries into the chambers after the chambers are tense.

Anatomy & structure

The tricuspid valve is also known as a leaflet valve for anatomical reasons, because it consists of three leaflets (cuspis) that serve as a locking mechanism. The three sails are named Cuspis angularis, Cuspis parietalis and Cuspis septalis.

Each of these cusps is connected to one of the three papillary muscles by means of several, partially branching, tendon threads (Chordae tendineae). The papillary muscles are small protrusions of the ventricular musculature, which, slightly offset in time by the electrical excitation of the ventricular musculature, can also be stimulated to contract. The contraction of the papillary muscles leads to the tightening of the tendon threads. Because the individual cusps are thin and the cross-section of the valve is relatively large in relation to the rigidity of the cusps, there is a risk that the cusps will be pushed through in the direction of the atrium after the valve is closed and pressure has built up in the chamber and thus lose their function.

The tensioned tendon threads prevent this. They serve, so to speak, as a built-in safety system to ensure the functionality of the tricuspid valve during systole. The counterpart of the tricuspid valve in the left ventricle is the mitral valve, which also functions as a leaflet valve. It has only two cusps, however, and its tendon threads are stretched by only two papillary muscles. Both leaflet valves are also known as atrioventricular valves.

Function & tasks

The main function of the tricuspid valve is its valve function as an outlet valve for the right atrium and an inlet valve for the right ventricle. During the systole of the right ventricle, it must close and make sure that no blood flows back into the right atrium during this pressure phase. During the diastole of the right ventricle and the almost simultaneous tension phase in the right atrium, the valve must open wide so that blood from the atrium can flow into and fill the ventricle as freely as possible.

The functionality of the tricuspid valve, together with the functionality of the other three heart valves, is important for maintaining the blood flow in the "correct" direction in the body. The blood, which first reaches the right atrium via the superior vena cava, collects there and flows into the right ventricle during diastole. It comes from the body's great circulation and is therefore oxygen-poor and rich in carbon dioxide. During systole, it is pumped into the pulmonary artery so that the exchange of substances in the capillaries in the alveoli can take place in the opposite direction. Carbon dioxide is given off and oxygen is taken up.

Diseases

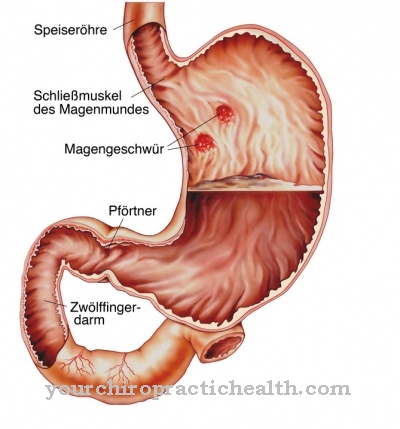

In principle, two different functional impairments, called heart valve defects, can occur in heart valves. If the valves do not open sufficiently, it is a stenosis. The opening through which the blood must flow does not correspond to the nominal cross section, so that the blood flow is impaired to a greater or lesser extent.

Otherwise the flap will not close properly. This consequently means that when pressure builds up in the contraction phase, part of the blood flows back again. In relation to the tricuspid valve, it means that during the systolic tension of the ventricular muscles, a more or less large part of the blood flows back into the right atrium, which manifests itself symptomatically in a loss of performance. Such leaks in the heart valves are known as insufficiency and are divided into different classes of insufficiency depending on the severity. However, the tricuspid valve is much less frequently affected by valve defects than its counterpart in the left half of the heart, the mitral valve.

Tricuspid valve stenosis or tricuspid valve insufficiency can arise, for example, from inflammation of the inner lining of the heart, or endocarditis. The inflammation can typically lead to shrinkage or scarring or even to a sticking of the leaflets, which are then restricted in their function, which typically manifests itself in a stenosis or insufficiency. In less common cases, tricuspid valve defects can be present from birth due to developmental abnormalities. In very rare cases, a tricuspid atresia, a complete absence of the heart valve, may be present at birth.

This means that the right atrium has no connection with the right ventricle. In this case, blood is usually mixed between the two atria via the breakthrough that was still present at birth, the foramen ovalis, so that oxygen-poor blood from the body's circulation mixes with oxygen-rich blood from the pulmonary circulation and leads to the resulting problems. In severe cases, tricuspid valves can be replaced by an artificial valve.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)