In the Internal jugular vein it is a vein in the head that extends from the base of the skull to the angle of the vein. At the jugular foramen, bleeding from the artery can damage cranial nerves IX to XI and lead to characteristic syndromes.

What is the internal jugular vein?

The internal jugular vein is one of the blood vessels in the head and neck and is part of the body's circulation. Blood flows through them from the head and towards the heart, where the vital organ takes the blood and then pumps it into the lungs. In the lungs, oxygen molecules can attach to the red blood cells (erythrocytes), while carbon dioxide diffuses out of the blood. The internal jugular vein contains oxygen-poor blood that collects in ever larger blood vessels from the brain.

The venous counterpart to the internal jugular vein is the external jugular artery or external jugular vein. It runs closer to the body surface than the internal jugular vein and also extends from the head over the neck to the angle of the vein or opens into the internal jugular vein. Compared to the internal jugular artery, however, the diameter of the external jugular vein is significantly smaller.

Anatomy & structure

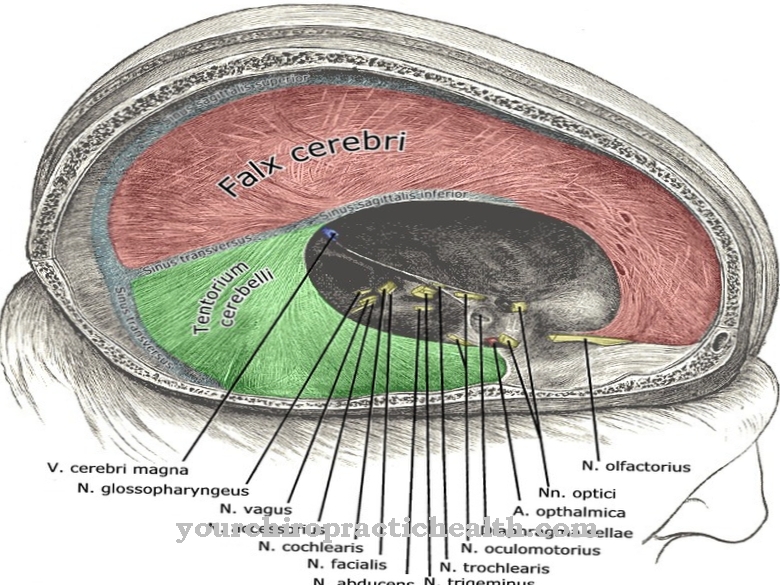

The internal jugular vein begins at the zygomatic vein opening (jugular foramen), which is located at the base of the skull. The anatomy also calls the passage a throttle hole. The blood vessel here lies next to the glossopharyngeal nerve, the vagus nerve and the accessory nerve.

The three nerves supply large areas in the head and neck with nerve signals. At the zygomatic vein opening, the sigmoid sinus flows into the internal jugular vein, which drains blood from the brain. In addition, the first expansion of the internal jugular vein is located here in the form of the superior internal jugular vein.

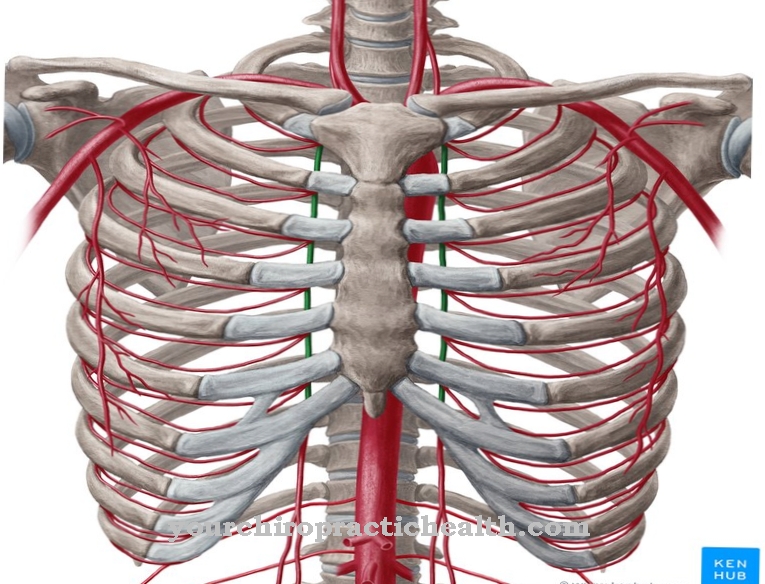

The internal jugular artery then follows the internal carotid artery (internal carotid artery) to its origin at the common carotid artery (common carotid artery). From there, the internal jugular vein accompanies the carotid artery through the neck and finally opens into the vein corner in the chest area. At this point the internal jugular vein meets the subclavian vein and has a second swelling, the inferior internal jugular vein. The internal jugular vein flows under the sternoclavicular joint (articulatio sternoclavicularis) in the brachiocephalic vein and ends there.

Function & tasks

The internal jugular vein has the task of absorbing oxygen-poor blood and conveying it to the vein angle. There the blood first flows into the brachiocephalic vein and then into the superior vena cava (superior vena cava), which finally forwards it to the right atrium of the heart (atrium cordis). The heart then pumps the blood into the small bloodstream or pulmonary circulation.

Before that, the internal jugular vein receives several tributaries. Among the most important are the fine junctions from the head area, which already open into the vein at the jugular foramen. They divert blood from the brain, which is used to supply the central nervous system. Proper drainage is important to avoid disrupting blood flow.

Deoxygenated blood flows from the face in the facial vein to the internal jugular artery. In an oxygen-rich state, her blood previously supplied numerous muscles of the face as well as connective tissue, nerves and other tissues. The pharyngeal veins also belong to the tributaries of the internal jugular vein and drain blood from the pharyngeal plexus. In addition to the external jugular vein, the tongue and meningeal veins as well as a thyroid vein use the internal jugular vein as drainage. The same applies to the sternocleidomastoid vein, the blood of which comes from the head nod (sternocleidomastoid muscle).

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines against memory disorders and forgetfulnessDiseases

Various complications, such as inflammation, are possible with jugular vein thrombosis. Internal jugular vein bleeding from the jugular foramen can damage the ninth to eleventh cranial nerves. Other injuries, tumors, inflammations and atrophy are also possible lesions in this region and lead to characteristic clinical pictures.

Avellis (Longhi) syndrome is caused by a lesion of the elongated medulla (medulla oblongata) and leads to neurological symptoms as the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves are damaged. The roof of the mouth, throat, and vocal cords are paralyzed on the side where the lesion is located. In addition, there is paralysis on one side (hemiparesis) of the opposite (contralateral) side. In addition, some people who suffer from Avellis syndrome feel pain and temperature only reduced (hemihypesthesia).

Another syndrome that regresses due to injury, bleeding, tumors, and other damage to the jugular foramen is Jackson or Schmidt syndrome. This also leads to hypoglossal paralysis - paralysis of the tongue is particularly characteristic. In contrast, the Sicard syndrome manifests itself in the form of nerve pain (neuralgia). The Vernet syndrome is associated with spastic paralysis and also manifests itself in other neurological symptoms such as taste disorders, which are due to the failure of the responsible cranial nerves. Villaret's syndrome is also due to a lesion of the medulla oblongata on the jugular foramen. This clinical picture paralyzes the facial nerve, the glossopharyngeal nerve, the vagus nerve and the accessory nerve on one side of the body.

In addition, medicine makes partial use of the internal jugular vein to insert a central venous catheter (CVC) into it. To do this, a doctor pushes the thin tube inside the vein up to the heart. Through the CVC, drugs such as cardiologically active substances, chemotherapeutic agents or electrolyte solutions can be administered directly to the heart. The CVC is also suitable for determining the central venous pressure. When examining the internal jugular vein, doctors use an ultrasound machine or other imaging techniques.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)