The Venous angle (Angulus venosus) form the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein, which merge to form the brachiocephalic vein. The largest human lymphatic vessel, the thoracic duct, is located in the left vein angle. The diseases of the lymphatic system include lymphedema and lymphangitis.

What is the vein angle?

The vein angle is also known in technical terms as the angulus venosus. It is located in the chest area of the human being and describes the angle at which the internal jugular vein (vena jugularis interna) and the subclavian vein meet and merge into a common blood vessel.

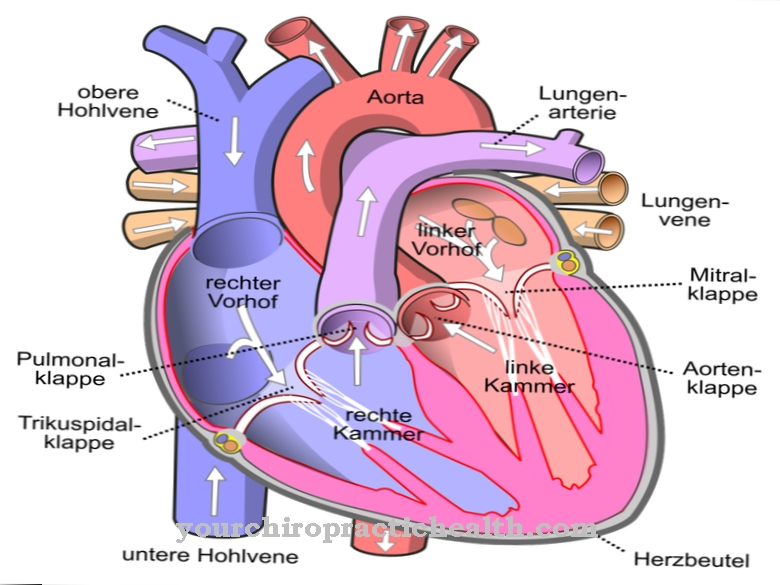

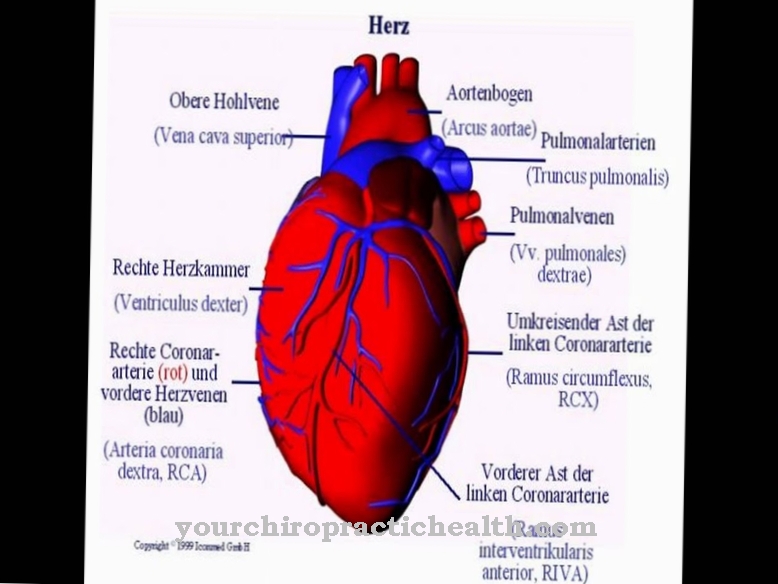

This united vein is the brachiocephalic vein, also known as the anonymity or innominata vein. In front of the heart, the brachiocephalic veins on both sides bend into the superior vena cava (superior vena cava) and in this way reach the right atrium. The vein angle belongs to the vascular system of the body circulation, which is colloquially also known as the great blood circulation. The veins carry the blood to the heart, which has previously supplied other organs with oxygen, energy and nutrients. When this blood reaches the heart, it is oxygen deficient.

Anatomy & structure

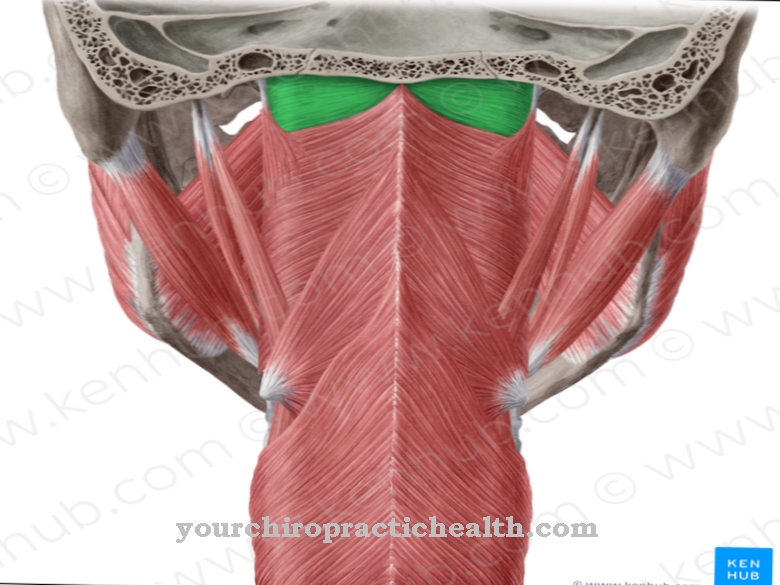

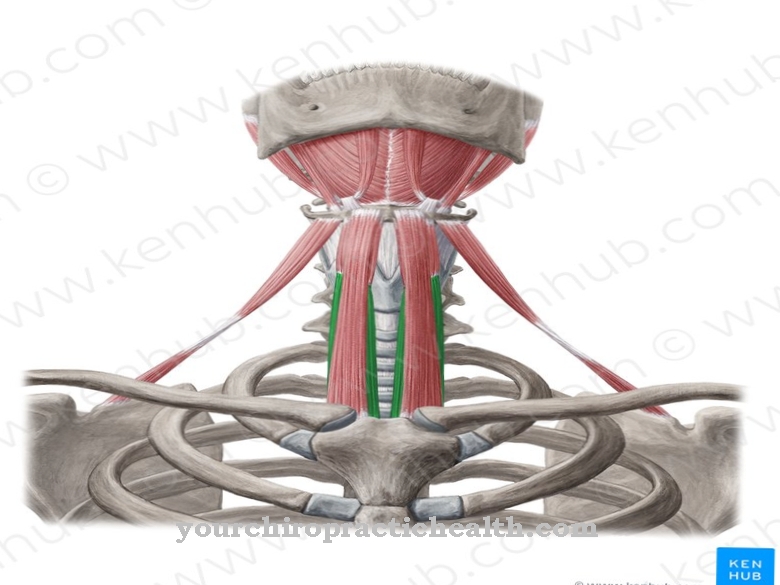

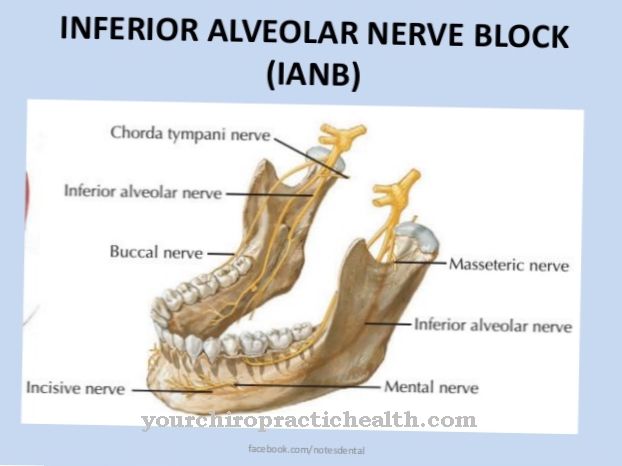

The internal jugular vein drains blood from the cranial cavity, which it receives at the zygomatic vein or throttle hole (jugular foramen). The passage lies in the posterior fossa cranii posterior next to the temporal bone. In addition to the jugular artery, the ninth cranial nerve (glossopharyngeal nerve) as well as the tenth (vagus nerve) and eleventh (accessory nerve) run in the jugular foramen.

The oxygen-poor blood flows out of the brain through finer vessels and collects in the superior petrosal sinus, inferior petrosal sinus and transverse sinus. All three blood conductors flow into the sigmoid sinus, which eventually flows into the internal jugular vein. The vein runs along the internal carotid artery (internal carotid artery) to the junction where the artery branches off from the common carotid artery.

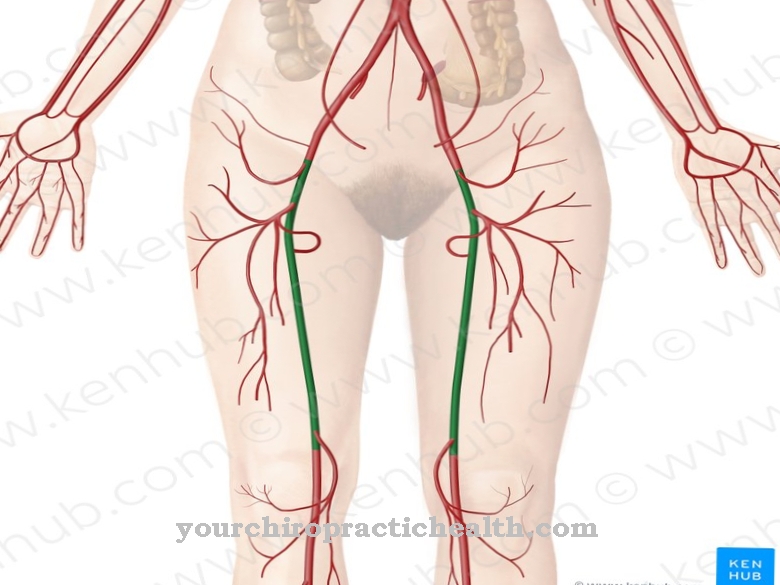

From there it follows the carotid to the angle of the veins, where it merges with the subclavian vein. This comes from the strong axillary vein, which runs in the armpit area and has valves that prevent the blood from flowing back. Its destination is the broad brachiocephalic vein. The vein angle is symmetrical in both halves of the body.

Function & tasks

The main function of the venous angle is to bring the blood of the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein together and unite it into the brachiocephalic vein. In addition, the lymphatic system directs its fluid into the bloodstream at this point. Medicine also uses the vein angle to record the relative position of anatomical structures to one another. The vein angle serves as a spatial orientation point.

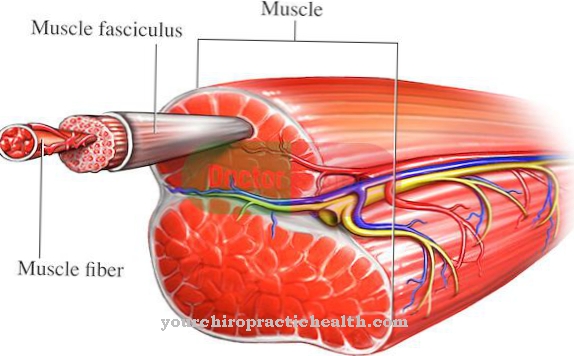

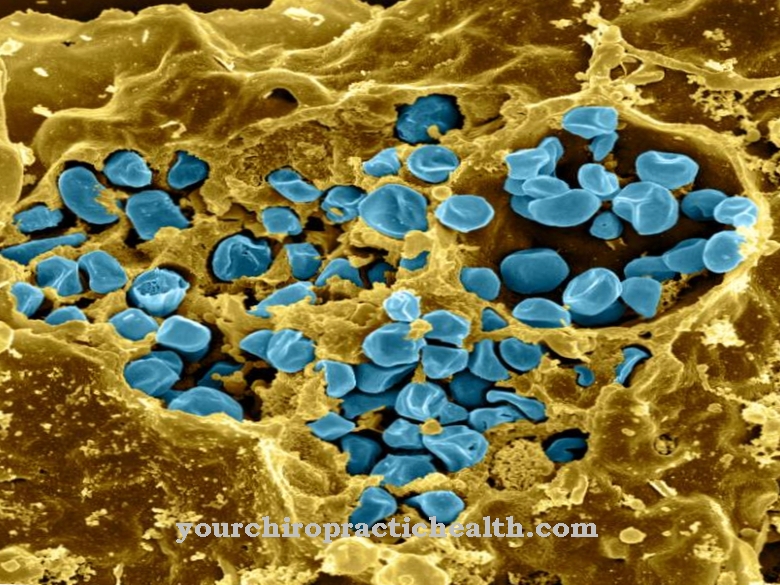

On the left is the left brachiocephalic vein, which at 6 cm is around two to three times as long as its right counterpart. Behind the vein angle, the strong blood vessel takes in more oxygen-poor blood from other veins. Via the heart, the oxygen-poor blood from the veins finally reaches the pulmonary circulation, where the red blood cells (erythrocytes) in the lungs are loaded with oxygen. The vein angle also exists in the right half of the body, but it is slightly smaller. The right brachiocephalica vein also receives blood from other veins and eventually merges with the left brachiocephalic vein.

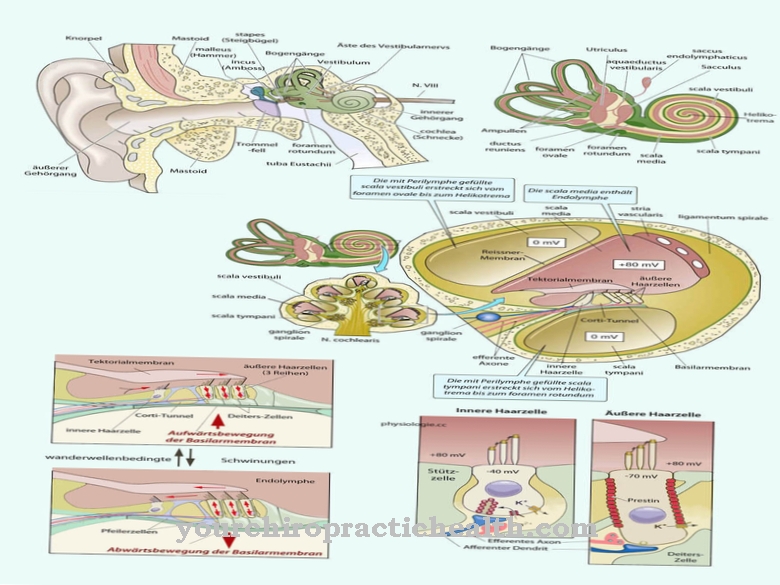

Other functionally important structures in the venous angle are the lymph vessels. The breast duct (ductus thoracicus) is a lymph duct in the left vein angle. It forms part of the immune system and has the task of transporting lymphocytes. These specialized white blood cells fight potential cancer cells and invading pathogens such as bacteria and viruses. The lymphatic system also prevents fluid and proteins from being deposited in the tissue between the cells. In the vein angle, the thoracic duct brings the collected fluid back into the blood vessel system. On the opposite side is the right lymphatic duct (ductus lymphaticus dexter). However, the lymph duct in this half of the body is significantly smaller than in the left.

You can find your medication here

➔ Medicines against edema and water retentionDiseases

The thoracic duct plays a central role in the functioning of the lymphatic system, as it releases the fluid and proteins it contains into the blood in the corner of the veins. Disturbances in the outflow of the lymph can cause lymphedema. Lymphedema shows up as swelling of the tissue and can cause pain.

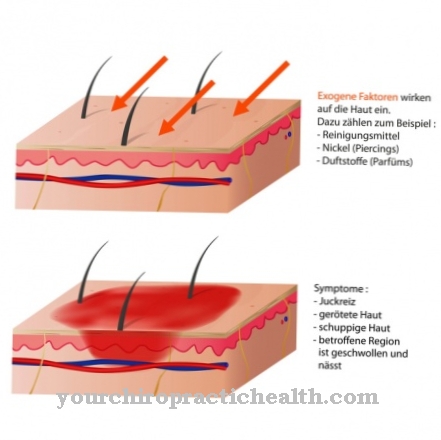

Hereditary lymphedema is caused by a design flaw in the drainage system, while in other cases the disease occurs after a mastectomy (mastectomy) or radiation for a breast cancer. However, not every swelling of the tissue indicates lymphedema: There are many different causes for edema, from excessive salt intake and food to electrolyte disorders and heart failure.

Medicine calls an inflammation of the lymphatic system lymphangitis. Bacteria, insect bites, parasites, drugs and other substances can cause the inflammation with their characteristic red stripes that rise up in the lymph vessels and are externally visible. In addition, palpitations, fever and chills may appear. Often the red stripe feels warm, throbbing and is accompanied by pain. As a concomitant phenomenon, lymph node swellings and blood poisoning (sepsis) are sometimes seen when the infection spreads to these vessels.

In addition to the signs of lymphangitis, symptoms of sepsis include diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, decreased urine output (oliguria), decreased blood pressure, rapid breathing (tachypnea), circulatory shock and (mostly quantitative) impaired consciousness.

.jpg)